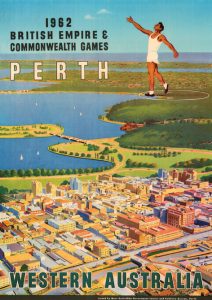

The 1974 British Commonwealth Games were held in Christchurch, New Zealand from 24 January to 2 February 1974. The bid vote was held in Edinburgh at the 1970 British Commonwealth Games. This was the second time that they had been held in New Zealand – the 150 version was in Auckland – and they had twice been in Australia – 1938 in Sydney and 1962 in Perth. They were all held in what would normally have been the Scots winter season with virtually no track racing at all and no permanent indoor facility either. They also came two years after the Israeli athletes had been kidnapped and murdered at the Munich Olympics and the tenth Games was the first big sports meeting to place the safety of spectators and participants as arguably its top priority. The Village was surrounded by security gards, police and the military had a highly visible presence. Despite all of that, however, many athletes from several countries decided to emigrate to New Zealand on the strength of their welcome and what they saw of the country.

The Games were officially named “the friendly games”. There were 1,276 competitors and 372 officials, according to the official history, and public attendance was excellent. The main venue was the QEII Park, purpose built for this event. The Athletics Stadium and fully covered Olympic standard pool, diving tank, and practice pools were all on the one site. There were always, whether the general public were aware of the fact or not, a theme tune for the Games – Edinburgh in 1970 had had three songs! The theme song this time was “Join Together”, sung by Steve Allen. The Games were held after the 1974 Commonwealth Paraplegic Games in Dunedin for wheelchair athletes.

Ron Marshall tells us in the ‘Glasgow Herald’ that Lachie Stewart was the standard bearer as Scotland the parade into the stadium wearing their white hats, blue blazers and white trousers. More interesting were the comments of Dr Roger Bannister on the topic of drugs and doping. He is quoted sas saying that the drug takers were safe at these Games. “Nobody will be banned from these Games but afterwards they can look out. A change in detection methods is being developed but not quickly enough to be brought into action. ” “The rules of international federations at the moment still need a degree of proof which at the moment isn’t possible. The improvement in testing methods coupled by firm action by the federations will put an end to this evil in th very near future.”

The Glasgow Herald reporter for the Games was Ron Marshall (whom we all thought had been the newspaper’s reporter for the last two Games although he had only had a byline for the Edinburgh Games) who made a very good job of it.

The first day was 24th January and the report began:

“Mary Peters, the Olympic champion, and Scotland’s Myra Nimmo had the distinction of getting to their marks this morning in the first heat of the first track event of the Commonwealth Games, the 100 metres hurdles of the pentathlon. Northern Ireland’s supporters were disappointed with Miss Peters’ winning time of 13.9 sec, which gave her 873 points, but the Scottish girl who finished second to her in 14.1 sec for 847 points proved to be fourth fastest on a chilly, dull morning. This was undoubtedly a promising start for the Uddingston girl and put her well into the medal reckoning.”

The heats of the men’s 100 metres brought a satisfying result in Scotland’s favour. Don Halliday, the AAA’s champion, looking extremely confident as he sped home inches behind the title holder, Don Quarrie (Jamaica), although I thought the Scot was unfairly treated in getting a time of 10.6, a tenth behind the winner. In the next heat Les Piggot, given the toughest draw of them all, battled tenaciously for a fourth place behind a formidable trio- George Daniels (Ghana), Lennox Miller (Jamaica), a Munich finalist. and Greg Lewis (Australia). From the results so far, it looks as if Piggot has the precious fourth fastest time, 106, good enough to put him intomorrow’s semi-final.

David Jenkins, bidding for a second major championship to add to his European 400 metres title, had little difficulty in winning his first round heat in 46.9 sec, one of the slowest qualifying times. Drawn in lane six he led all the way but was hard pressed towards the tape by the New Zealand record holder, Bevan Smith. Jenkins’s main rivals for the title, Julius Sang and Charles Asati, both from Kenya, qualified with even more ease, and Jenkins has no simple task ahead of him”.

Unfortunately it was also the end of Myra’s pentathlon hopes as she failed to complete the five disciplines and ended ‘dnf 847 pts’, but the outlook was promising. After the successes of Edinburgh in 1970, confidence was high in the Scots camp. Myra was coached by team coach Frank Dick whose stock was high after 1970, and she still had her specialist event, the long jump to come.

The decathlon finished on Sunday 27th, a day christened ‘Black Sunday’ by the ‘Herald’. After the real Black Sunday in Munich two years earlier it was maybe a bit tasteless: the two events could not have been more different, but it was undoubtedly a bad day for the sport in Scotland. Going in to that day we had Stewart McCallum and Kidner in the decathlon, Halliday in the 200m heats, Alison McRitchie in the 200m (two rounds – heat and semi-final on the same day), David McMeekin in the 800m semi-final, and others like Rosemary Wright, Margaret Coomber, and Norman Morrison all in action. The report was honest and direct, almost to the point of brutality, and read:

“Black Sunday would not be too dramatic a way to describe the few hours Scotland’s athletes spent on a sun-drenched track here today. They virtually walked into a wall of superior opposition and never knew what hit them. It was distressing to witness. One of our major hopes for a gold medal, Stewart McCallum, saw his decathlon bid crumble as he failed three times at his opening height in the pole vault. That in itself was bad enough but for that height to be two and a half feet below his best turned out to be typical of our efforts from the morning to the early evening. Although he still had two events to take part in, Stewart called it a day and sped off to the Village. There was little reason to be hanging about after having gifted varying amounts of points to his opponents. …. Latterly it was David Kidner who carried Scotland’s decathlon flag with some distinction. Having ended the first day in seventh place, he buckled to with courage this afternoon and vaulted 14′ 1 1/2” , his highest ever. But, as usual, his 1500m looked painfully pedestrian. There was nothing he could do in this last event to save the second place he had so painfully reached.

Tonight he wanted to rebut the criticisms he always hears about his 1500m. “People keep talking about that bit of my decathlon. What they forget are the other bits I’m good at – pole vault, long jump, high jump and so on.” He was placed fourth with 7188 points. But how near he had been to climbing on to the medal rostrum.

But back to the Black Sunday tag. In brief it reads like this – Don Halliday out in the 200m heat, Alison McRitchie out in the 200m heat, Helen Golden out in the 200m semi-final, David McMeekin out in the 800m semi-final, Margaret Coomber and Rosemary Wright fail to make the 800m final, Norman Morrison ninth in 5000m heat.

Frank Dick, the national athletics coach, could hardly be blamed for trudging wearily out of the athletics stadium. His reasons for today’s disaster are worth recording. “We under estimated the opposition. We came out here totally unaware just how advanced some of these countries are but we know now – only too well.” He shook his head as if in disbelief. “I can’t describe how disappointed I am – it’s been an awful day’s athletics for Scotland.”

But before the picture is painted irredeemably black, it should be added that there were bright patches. David Jenkins crossed home in his 200m heat clocking 21 sec, a tenth behind the Ghanaian speedster George Daniels. The Scot earned himself an extra cheer for assisting the African off the track after he had seemed to injure himself at the finish. Ian Stewart qualified easily in his 5000m heat but a few grandads might also have squeezed through, bearing in mind that in the two heats the first six qualified. Only two had to be discarded in Stewart’s heat won by an over-exuberant Kenyan, Joseph Kimeto, who appears to have taken this contest for the final. Others did it the easy way.”

Frank Dick’s comments were simultaneously typical in their honesty and shocking in their content. There were those who attributed the Scottish athletic successes in 1970 at Meadowbank to John Anderson’s influence: he had been Scottish national coach until late 1969. However that may be, 1974 was all Frank in terms of preparation and it must have hurt him to say what he did. It didn’t happen again. The results that Marshall referred to:

Men’s 200m: H1: 2nd D Jenkins 21.0; H5: 4th D Halliday 21.7

Women’s 200m: H3: 5th A McRitchie 24.4; H5: 2nd H Golden 23.9

Women’s 200m: SF 1: 5th H Golden 23.9

Men’s 800m: H3: 4th D McMeekin 1:49.1 SF 2: 5th D McMeekin 1:48.1

Women’s 800m: H1: R Wright 3rd 2:06.3; H2: M Coomber 5th 2:06.5

Women’s 800m: SF 1: M Coomber 5th 2:05.9; SF 2: R Wright 5th 2:05.7

Men’s 5000m: H1: 2nd I Stewart 13:57.2; H2 N Morrison 9th 14:40.6

Shot Putt Women: R Payne 7th 14.07m

David Jenkins was one of the Scots in action the next day when he was second to Australian Greg Lewis in the semi-final of the 200m but then could finish no better than sixth in the final in a time of 21.5. Ian Stewart went one better in the 5000m to be fifth in 13:40.4 in a race won by Ben Jipcho of Kenya in 13:14.4 with Brendan Foster second in 13:14.6. Kenya also won the 800m Kipkurgat won in 1:43.9 from Mike Boit, also of Kenya, in 1:44.9. That was it for the day as far as Scots were concerned – no high or long jumpers, no javelin throwers and no race walkers or hurdlers had been entered.

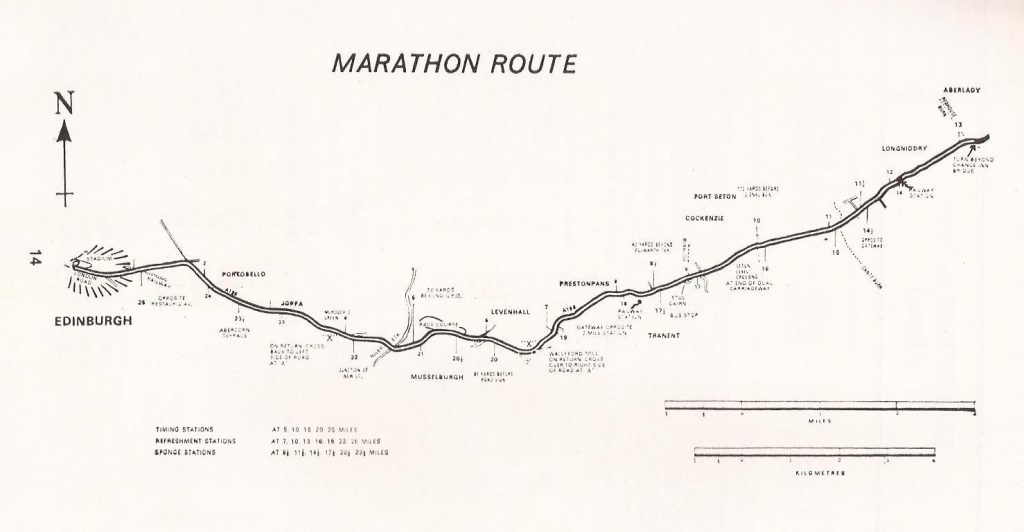

30th January was a rest day as far as athletics was concerned but it gave the reporters time to devote to other sports where Scotland was performing nobly – Willie as a bowler and David Wilkie in the swimming pool – but Ron Marshall took the opportunity to look forward to Lachie Stewart running in the marathon on the following day. Lachie had carried the standard on the opening day and then stood out in the centre of the arena for the duration of that ceremony: many questioned th wisdom of this the day before his specialist event of 10000m. In that race he did run below his usual to finish tenth in 29:22.6 while Ian Stewart was sixth in 28:17.2 and Norman Morrison was fifteenth in 30:25.8. The selectors had also entered him in the marathon – a distance he had never tackled seriously before, if in fact he had ever tackled it. The furthest most had seen him run was the 16 miles of the Clydebank to Helensburgh road race. Under the heading of ‘Lachie tackles marathon’ he wrote

“Scotland’s Lachie Stewart will make his marathon debut in the Commonwealth Games at Christchurch today and is a quiet tip to upset the fancied English and Australian gold medal hopes. Stewart is better known as a 10,000 metres runner and proved his class by winning that event in Edinburgh in 1970.

He has never run a competitive marathon, byt Scotland’s team manager Peter Heatly states, “Lachie doesn’t say very much, but we know he is extremely fit. He has been doing plenty of hard cross-country running the last few months and we think he has had the marathon at the back of his mind for some time. He is such a determined fellow, and he would not go in the marathon unless he thought he could give a good account of himself.”

The way Stewart ran in the 10000 metres last Friday suggested he had high hopes in the marathon, He finished 10th.

The marathon favourites are the Australians Derek Clayton and John Farrington, and the defending champion, England’s Ron Hill. …. Hill, sixth in the Munich Olympics, has the best time of the strong British contingent with 2:09:26, although he was beaten by Ian Thomson (Luton) in the October trial. Scotland have two other contenders besides Stewart in Donald Macgregor, a teacher and university lecturer, and Jim Wright, a student. Macgregor has the better time, 2:15:06.”

It is possible that the reporter was being a bit over optimistic about Lachie’s chances in a new event – especially over the 26 miles of the marathon and in the Christchurch temperatures. He certainly damns his run in the 10000 with faint praise. And it was possibly a bit hard on Donald Macgregor – after all, he was only one place behind Ron Hill in the Olympic marathon in 1970, and had actually been in front of him when they came on to the track with only ab out 400m to go at the end of the race.

As it turned out, Ian Thomson won the marathon for England in 2:09:12.2. In the course of a longish report on the event, the Scots only got one paragraph. “Donald Macgregor was Scotland’s first man home in the marathon in sixth place and he recorded his fastest time – 2:14:15.4. Both Lachie Stewart and Jim Wight pulled out of the race, Stewart after halfway and Wight not much further along the route.” The experienced Macgregor who had run in Commonwealth and Olympic marathosn with distinction, who had won Scottish titles over the distance proved to be the best of the three over the distance.

Other events that day included the women’s 1500m in which Ian Stewart’s sister Mary qualified for the final when she was third in her heat in 4:15.3, the women’s long jump where Myra Nimmo was fourthwith a best leap of 6.34m, only 4 cm behind the third placed Reid of Wales.

The final day of athletics was February 2nd when there were Finals of the men’s 1500m (no Scots were entered), men’s 4 x 400m in which no team was forward, men’s shot putt (no Scot taking part), men’s javelin (no one entered) and women’s 4 x 400m with no Scots entered. On the other side we had representatives in the men’s 4 x 100m relay (5th in 39.8), men’s triple jump (W Clark 11th), women’s 1500m (Mary Stewart 4th 4:17.4), women’s 4 x 100m (7th in 46.5) and women’s high jump (Ruth Watt 4th 1.78 – missed bronze by 2 cm). Over the piece there was only one medal for the Scottish team, silver in the women’s discus from Rosemary Payne (53.94m).

Ron Marshall’s review of the Games included the following:

“One silver medal from a corps of 27 athletes is a particularly poor return from what we were calling the best prepared team to travel to any major competition. Perhaps we did too well in Edinburgh. Perhaps that is the subtle burden placed on every host. It will be interesting therefore to see whow New Zealand , one of the successful nations here, fare in Edmonton four years from now. No explanation, no rational one anyway, has come from any of our team leaders. If blame lies anywhere, is it with the athletes themselves or their own coaches, or the team coaches and officials? I find it hard to fault team management, if they erred it was on the side of leniency.

One comment from Frank Dick, national athletics coach, early on in the week, keeps coming back: “we under estimated the opposition.” Mr Dick is abreast of world progress in athletics – he obviously knew what to expect. Clearly the competitors did not. Talk of an inquiry when the team comes back is just that – talk. No amount of discussion will produce a solution to what happened. But one answer will be to send a much smaller athletics team next time round. Feelings, not to mention thousands of pounds, will be spared now that Scotland have no obligation to fatten up the team just for the parade and the opening ceremony. We will not march first into the stadium in Edmonton.”

One silver medal was indeed a disappointing return from the team but I think maybe the reporter was being a bit easy on the officials. For instance, the management of Lachie Stewart’s Games was seriously badly thought out. The notion that he should be the standard bearer and stand in a draughty arena for hours on end the night before his 10,000m race was a bad one. He should maybe have missed the parade altogether. Then to add in his marathon debut – debut – against the best in the Commonwealth only a few days later was a bit lacking in judgment. If there was a desire to give him two races, then the 5000m or the steeplechase would have been better bets. Myra Nimmo was an outstandingly good long jumper with a chance of a medal – surely that should have been the target rather than greedily going for two medals? And if ‘we’ under estimated the opposition, who was in charge of the group team meetingsand get-togethers for the four years leading up to the Games? If Frank Dick was really up on the world situation,should the information not been impressed on the athletes before the Games?

Other events that day included the women’s 1500m in which Ian Stewart’s sister Mary qualified for the final when she was third in her heat in 4:15.3, the women’s long jump where Myra Nimmo was fourthwith a best leap of 6.34m, only 4 cm behind the third placed Reid of Wales.

The final day of athletics was February 2nd when there were Finals of the men’s 1500m (no Scots were entered), men’s 4 x 400m in which no team was forward, men’s shot putt (no Scot taking part), men’s javelin (no one entered) and women’s 4 x 400m with no Scots entered. On the other side we had representatives in the men’s 4 x 100m relay (5th in 39.8), men’s triple jump (W Clark 11th), women’s 1500m (Mary Stewart 4th 4:17.4), women’s 4 x 100m (7th in 46.5) and women’s high jump (Ruth Watt 4th 1.78 – missed bronze by 2 cm). Over the piece there was only one medal for the Scottish team, silver in the women’s discus from Rosemary Payne (53.94m).

Ron Marshall’s review of the Games included the following:

“One silver medal from a corps of 27 athletes is a particularly poor return from what we were calling the best prepared team to travel to any major competition. Perhaps we did too well in Edinburgh. Perhaps that is the subtle burden placed on every host. It will be interesting therefore to see whow New Zealand , one of the successful nations here, fare in Edmonton four years from now. No explanation, no rational one anyway, has come from any of our team leaders. If blame lies anywhere, is it with the athletes themselves or their own coaches, or the team coaches and officials? I find it hard to fault team management, if they erred it was on the side of leniency.

One comment from Frank Dick, national athletics coach, early on in the week, keeps coming back: “we under estimated the opposition.” Mr Dick is abreast of world progress in athletics – he obviously knew what to expect. Clearly the competitors did not. Talk of an inquiry when the team comes back is just that – talk. No amount of discussion will produce a solution to what happened. But one answer will be to send a much smaller athletics team next time round. Feelings, not to mention thousands of pounds, will be spared now that Scotland have no obligation to fatten up the team just for the parade and the opening ceremony. We will not march first into the stadium in Edmonton.”

One silver medal was indeed a disappointing return from the team but I think maybe the reporter was being a bit easy on the officials. For instance, the management of Lachie Stewart’s Games was seriously badly thought out. The notion that he should be the standard bearer and stand in a draughty arena for hours on end the night before his 10,000m race was a bad one. He should maybe have missed the parade altogether. Then to add in his marathon debut – debut – against the best in the Commonwealth only a few days later was a bit lacking in judgment. If there was a desire to give him two races, then the 5000m or the steeplechase would have been better bets. Myra Nimmo was an outstandingly good long jumper with a chance of a medal – surely that should have been the target rather than greedily going for two medals? And if ‘we’ under estimated the opposition, who was in charge of the group team meetings and get-togethers for the four years leading up to the Games? If Frank Dick was really up on the world situation, should the information not been impressed on the athletes before the Games?

Finally we have some thoughts from Willie Robertson who competed in these Games as a wrestler. He was also a nationally ranked throws athlete with several SAAA hammer throwing medals and three times GB wrestling champion. He says:

I realised I had to win the British title at wrestling to be sure of selection. I checked the English results and the 100Kg plus weight group looked easier than the 100kg. I won the Scottish title at 100Kg beating Ian Duncan, a team mate. My plan was to win the British and ask for selection to the team at the lower weight group. At the British I won the title at 100Kg+, however Ian Duncan won the 100Kg. So they picked Ian at 100 and me at 100+. Yes, the best laid plans. At the games two of the wrestlers were struggling to make the weight and were on a strict diet. I had the opposite problem. Because I was on full time training I had to eat large meals to maintain my weight.

There was a squad day for the better NZ hammer throwers who did not make the Commonwealth team. Bryce, Black, myself and the weightlifter Grant Anderson took on the NZ second team It was decided on an aggregate score would be used. Howard Payne acted as judge. We were beaten. Grant threw an impressive 40m with a standing throw. Bryce suggested I should not be suggesting he tries the Highland Games. Of course he won the Scottish professional title a couple of times.

I met up with a Samoan trying to throw the hammer. I gave him some coaching and he got on to a one turn throw. He said he was a decathlete and the head of sport had contacted him and said he should enter all the throws. I went along to the stadium to watch the hammer. Chris Black was in with a chance of a medal. There were nine competitors which meant one would be eliminated. Chris had two narrow fouls in the first two rounds. He was forced to do a two turn throw for his third to get another three throws and beat the Samoan. If the ninth thrower had not been there Black would have had an extra counting throw. He might well have won a medal. Bryce was last in the final. The problem was the technique had moved on. It is interesting to compare the 1970 and 74 standards. Bryce was coached to drag the hammer: every other thrower in the final was on to a using two straight arms.

One of my great memories of the athletic was the 1500m. Filbert Bayi was a front runner and lead from the start. The only runner who looked that he might catch him was John Walker. Not only Bayi had broken the World record, Walker had had also beaten the old one I was sitting beside Bryce who remarked that he wondered how Frank Clement would have done in that race.

The athletes were aware they were receiving some bad press for their performance. After the 1970 games there was great expectation of a number of medals. There were a few ‘near misses’ I remember seeing Jenkins in the last leg of the 4x100m relay making the school boy error of looking behind him when receiving the baton. They should have won a medal. Our best decathlete no heighted in the pole vault. Frank Clement, our lead middle distance man had missed the games for University exams. Lawrie Bryce, with his usual wit, paraphrased the words of Churchill: Never in the history of the Commonwealth Games have so many, went so far to do so little.

The team met up at the Royal Scot hotel in Edinburgh. After dinner and some speeches we wrestlers were told to go to bed by our coach. Half an hour later Lawrie Bryce knocked at the door and demanded I went for a drink with him. Bryce had not reached the qualifying standard in the hammer for selection but had been added later. This was his third games. He wasn’t expecting to do well. He more or less saw the trip as a wee unexpected holiday at the end of his throwing career. You must also remember the games were held at the end of the Heath government with the three day week, power blackouts and TV closing at 10. It was a great time to have a month in the sun.

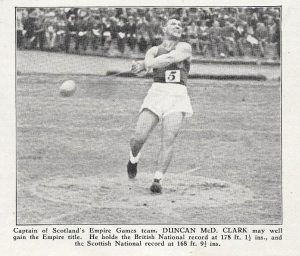

I went with Black and Bryce to visit Duncan Clark, a former Empire games gold medallist and Scottish record holder? I believe he liked New Zealand when he attend the games and decide to emigrate there. I think Euan Douglas did the same thing. He competed at Perth Games and decided to emigrate there later.

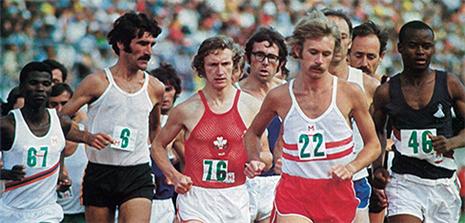

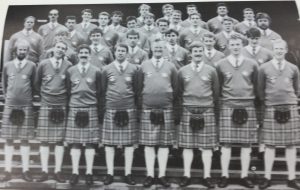

Men’s Team: John Brown, centre front

Men’s Team: John Brown, centre front

Liz with some of the other Scots at the Games

Liz with some of the other Scots at the Games