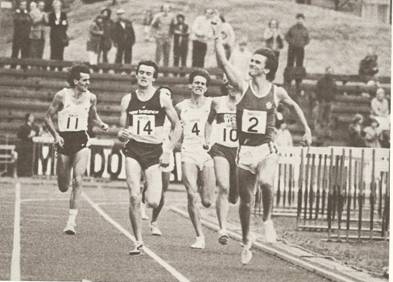

Ian Gilmour (2) and Alistair Blamire (1)

Ian Gilmour, born in Salisbury (Wiltshire) of Scottish parents, is a Scottish International athlete whose exploits are known to very few in the sport at present. An international runner on the track and over the country, he ran for both Scotland and Great Britain while based in the English midlands where he was a member of the Wolverhampton and Bilston club. For a spell, Clyde Valley had probably the best steeplechasing double act in the United Kingdom with Ian and John Graham being the men responsible. The following profile has been written by their Monkland Harriers/Clyde Valley AAC team-mate Joe Small, who tells me that with Jim Brown having run a steeplechase in 9:06, the club probably had the best act in Britain. Over to Joe.

Ian Gilmour was an Anglo-Scot, born in January 1952, who managed to maintain a remarkably low profile whilst becoming a Great Britain internationalist and competing for Scotland at Commonwealth Games and in the World Cross-Country Championships. An Ayrshire born father qualified him to compete for Scotland Primarily known as a steeplechaser on the track, he was equally adept on the road and over the country.

He started his athletics career as a high jumper and was good enough to win the English schools junior title in 1966, equalling the championship record. He started to show some promise as a cross country runner around the same time, winning his county title having finished seventy third the year before. He only started training seriously when he started at Birmingham University in 1970.

He first came to prominence in Scotland when finishing third behind Ronnie McDonald and Jim Brown in the 1971 Scottish Cross-Country Championships junior race at Bellahouston Park. As a total unknown he hitchhiked up to Glasgow to compete and remembers Jim Brown saying to him after the race, “Who are you?” Discussions then followed between Ian and Tommy Callaghan, who coached Ronnie, and Ian thereafter ran for Monkland Harriers and subsequently Clyde Valley AAC when in Scotland. Following that third placing he competed in the ICCU World Junior Championships, finishing in thirteenth place in 24:49, which along with Jim Brown in third in 24:02 and Ronnie McDonald in fourteenth in 24:51 resulted in the Scottish team picking up the silver medals behind and England team consisting of Nick Rose, Ray Smedley and Steve Kenyon., an excellent result for the young Scots. On teh track in 1971 he was timed at 8:25.6 for 3000m indoors and was ranked third in the Scottish junior lists over 5000m with a time of 14:31.2, the two runners ahead of him being Jim Brown and Ronnie McDonald. Improvements in 1972 saw him record times of 3:51.7 for 1500m, and at 3000m and 5000m times of 8:11.6 and 14:07.0 ranked him fourth and tenth respectively in the Scottish senior lists for the year.

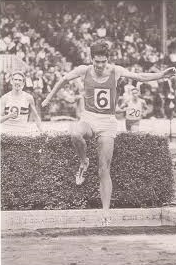

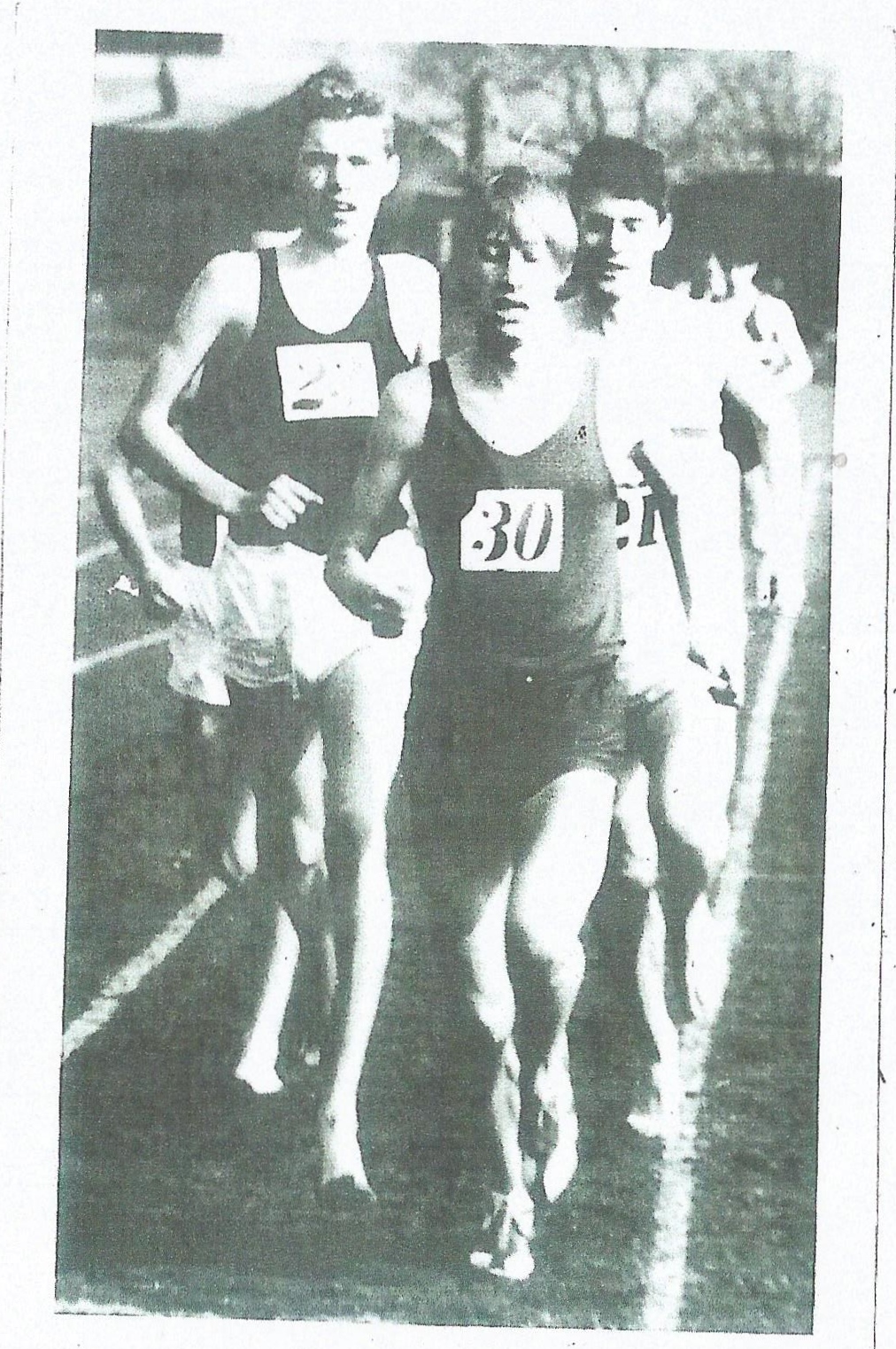

Ian is Number 6 behind Dennis Coates, number 18

1973 saw his first recorded steeplechase times. Indoors a third place Phillips Cosford Games in 5:35.6 kicked off his season. He finished fourth in the British Clubs Cup final with a time of 9:19.6 for the steeplechase, ending the year third in the Scottish rankings with a time of 8:56.6 behind Alistair Blamire and Bill Mullett. 1974 started with a victory in the AAA’s indoor 2000m steeplechase with a time of 5:34.6, good enough for second in the UK Ranking list. He also picked up a bronze medal in the World University cross-country championships. Outdoors in summer he had an early season clocking of 8:58.6 in a British League fixture, finishing second behind Gareth Bryan-Jones, followed by a third place finish in the Inter-Regional Championships with a time of 8:53.6. With four runs during the summer between 8:45.0 and 8:45.4 including second in the SAAA Championships, ninth in the AAA’s, third in the Scotland v Norway and third in the AAA’s inter-regional championships, he produced his consistently good performances, sufficient to rank tenth in the UK Best Performer lists for that year. At other distances, a 3:48.5 1500m indicated improvement at the shorter distance, he also recorded 8:17.0 for 3000m at Crystal Palace in a race which Ronnie McDonald won in 7:55.4.

The next year, 1975, saw further gains as he topped the Scottish rankings with a steeplechase best of 8:43.6. With six runs under nine minutes, including victories in the British Universities Championship, Scotland v Iceland, third in the British Cup match behind John Wild and Andy Holden and fourth in the Inter-Regional Championships, his position as Scotland’s number one steeplechaser was confirmed. At 5000m he finished fourth in the Scottish Championship in 14:04.0 behind David Black, Jim Brown and Jim Dingwall. An injury-hit 1976 followed with only two early season results recorded. Following an indoor 3000m in 8:12.6, a 5000m of 14:14.4 and an 8:59.2 steeplechase, both in May, were the only notable times for that year. The steeplechase time still saw him ranked third in Scotland.

Back in action in 1977, a victory in the AAA’s Inter-Counties championship in difficult conditions with a time of 8:48.4 was followed a week later with fourth in the UK championships with a personal best of 8:40.9. In the European Clubs Cup final Ian finished third in 8:48.8. The Phillips Gateshead Games saw a sixth place finish in 8:35.8, another personal best, the race being won by the Ethiopian, Tura. At 1500m he ran 3:48.9 in the AAA v Loughborough match and 3:51.5 in a British League fixture, finishing second to John Robson.

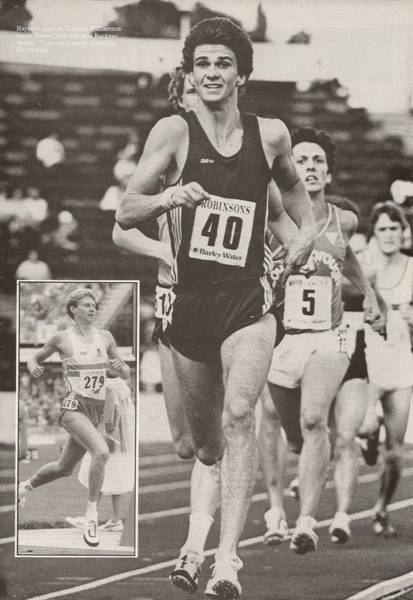

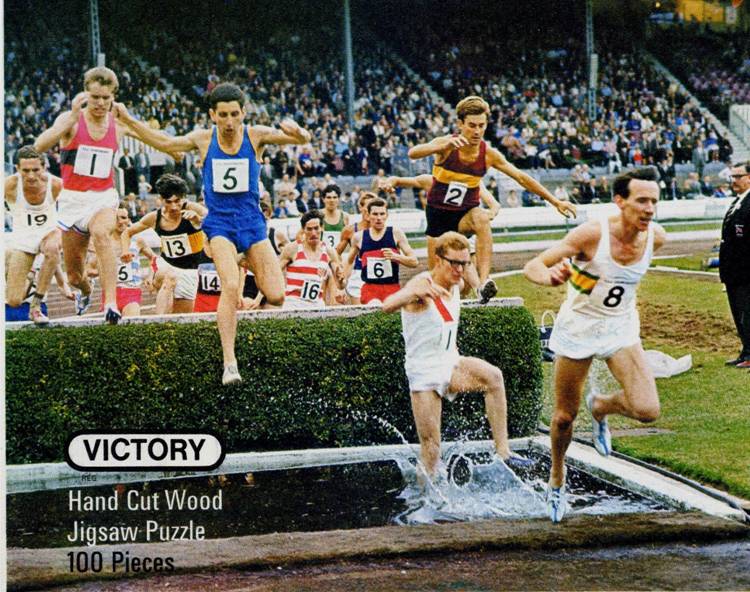

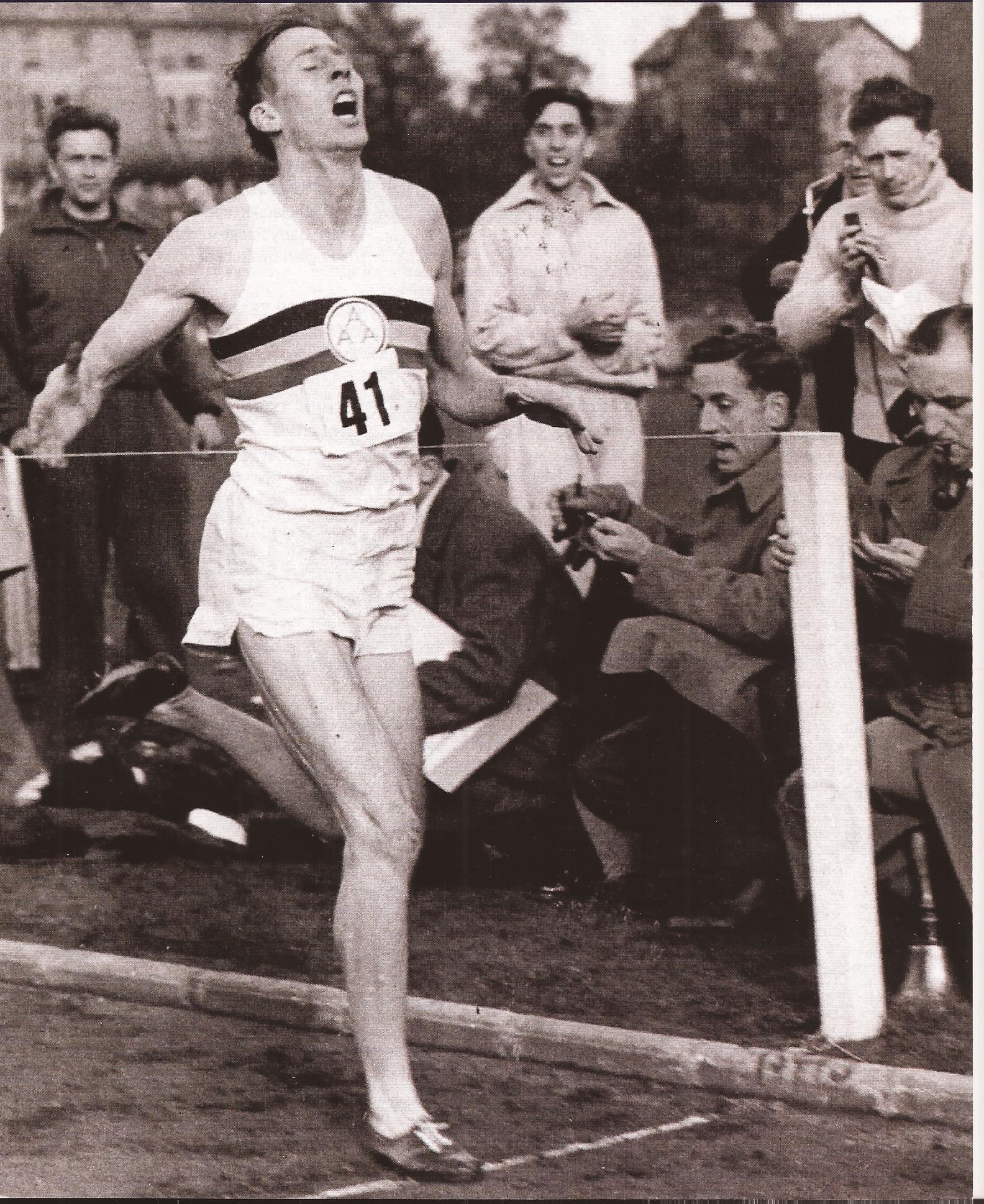

Arguably, Ian’s best year was to follow. In 1978 he ran his fastest ever time and represented Scotland in the Commonwealth Games in Edmonton. He ran a 1500m personal best of 3:47.6 in a British League Match finishing second to fellow Scot Laurie Reilly with a 5000m in 13:57.6 soon after. In the steeplechase, a British League match in early May saw victory in 8:48.8 heralding good times to follow. Ian was picked to represent Great Britain v East Germany over 3000m steeplechase in June. However the results seem to indicate that no steeplechase took place, instead he finished eighth in 14:35.08 with Lawrie Spence seventh. Nick Rose won in 13:26.6. Fourth place at the Phillips Night of Athletics at Crystal Palace in a time of 8:45.2 was followed by victory in the SAAA Championships in a time of 8:38.9, setting a National record and championship best performance; in second John Graham set a Scottish Native record of 8:44.1. In July Ian finished third in the UK National Championships at Meadowbank setting a new national record of 8:31.09 behind Dennis Coates and John Davies and securing a place in the Commonwealth Games team.

A fifth place in the AAA’s Championships in 8:43.7 followed.. At the Commonwealth Games in Edmonton, fourth in his heat in 8:56.53 secured his place in the final where he eventually finished eighth in 8:49.7, the winner being Henry Rono who led a Kenyan 1-2-3 for the medals. In September he ran 8:06.6 to finish fourth in a very close 3000m race at the McEwan’s Games in Gateshead, Steve Cram winning in 8:05.8 from Julian Goater, 8:06.0, and Lawrie Spence, also 8:06.0!

1979 saw another good run indoors to win the AAA’s 2000m steeplechase in 5:40.2. Outdoors two runs at Gateshead proved notable. A 5:35.95 2000m steeplechase for fourth on the the Scottish All-Time list. His first outdoor steeplechase saw an 8:34 timing, however an injury three days later prevented him running in the Europa Cup having just been chosen for the British team. A second place over 3000m steeplechase in the Gateshead International Games in 8:34.8 behind Rosendal of Norway, saw him again top the Scottish ranking list. A late season 5000m timing of 13:50 was followed by more injury, which together with a bout of food poisoning finished his season. A notable run on the roads saw him record a time of 47:25 for ten miles at Barrow.

After recovering from a bout of pneumonia in October 1979, he went altitude training in April 1980, however further injury in May 1980, to quote Ian, “ended my Olympic dream I was in the form of my life when ity happened.” Other performances that year were second to Gordon Rimmer in the Scottish Championships in 9:01.9, in the UK Championships he failed to qualify for the final with his time of 9:16.45 although later in the year he clocked a time of 8:43.75 and in the IAC/Coca-Cola International finishing in eleventh place. In September he competed in the British Meat Games finishing seventh in 8:51.55. At the AAA’s Championships a time of around nine minutes saw an eighth place finish. In 1981 he had times of 8:50.2 for second in a match in Yugoslavia, 8:59.6 for second in the SAAA Championships and 9:01.0 gave him a fourth place finish in an international in Greece.

Having moved to Teeside in 1981 (and trained with Denis Coates) he had, by his standards a poor year while adjusting to the new environment. In 1982, having decided to concentrate on road running, he produced a third place finish in the Great North Run behind Mike McLeod and Kevin Forster. A time of 29:19.9 for 10000m on the track was followed by a 28:51 10K on the roads in Manchester. Numerous road race wins in 1982 culminated in victory in the Holmfirth 15 in November, timed at 75:03. He also surprised himself by recording a personal best 8:01 for 3000m on the track at Stretford behind Dave Lewis. His career at the top level ended in 1983. However there was an attempt (unsuccessful according to Ian) at the marathon distance recording 2:27 in London,”I knew I was struggling beyond the halfway mark and it showed.”

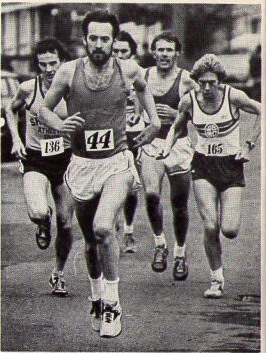

Ian Gilmour (186) in a road race in England for Wolverhampton and Bilston

On the roads, his best running came in the Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay. He took part in the race on six occasions, appearing to have a preference for the fourth stage. Aftre running the Second Stage in his first appearance in 1972, he finished fourth on the First Stage the following year. He ran equal fastest on the fourth stage in 1974 sharing the same time as steeplechase rival Alistair Blamire. 1975 saw him run the fastest leg on Stage Four to help Clyde Valley to third place, repeating the fastest time on the Fourth Stage in 1980 as Clyde Valley won the race for the second time in a row. One other run to be mentioned was in the inaugural Scottish Six Stage Road Relay in Strathclyde Park in 1979. Picked to run the last leg, Ian was handed a lead of 26 seconds over Edinburgh Southern Harriers with a close finish anticipated. Unfortunately he was up against an inspired Allister Hutton who closed the gap within two miles and finished over 90 seconds ahead of Ian. As he passed us near the finish he shrugged his shoulders as if to say, “What could I do?”

Equally at home on the country, he represented Scotland on four occasions at the IAAF World Championships with a best placing of 74th in 1973. Further finishes were 110th in 1975, 84th in 1978 and 122nd in 1981. At the Scottish Cross-Country Championships his best performance was a third placing in 1975 behind winner Andy McKean and runner-up Adrian Weatherhead. Other results included eighth place in 1973, sixth in 1978 and fifth in 1981 helping Clyde Valley to third place in the team race.

What happened next? Now living and working in Austrralia, Ian is qupoted as saying “work took over, but I have never stopped training. I love it too much. I took up triathlon when I moved to Australia and finished tenth in my age group at the 2009 World Championships at the sprint distance, representing Australia.” He also says that prior to concentrating on athletics when he was eighteen, his main sporting interest was golf where he played off a handicap of 4! Ian says “Having a Scottish father who got me taught by a professional; when I was ten was a great help” An outstanding all round sportsman then: high jumper, golfer, steeplechaser, road and cross country runner and now a triathlete!

In summary, Ian was an excellent all-round distance runner, whose time of 8:31.1 for the 3000m steeplechase still ranks fourth on teh Scottish All-Time list, 23 years later, and his 8:38.9 SAAA title win in 1978 still remains the Championship Best Performance. On a personal note, having run on the same team in a number of races with Ian I would describe him as a very modest, thoroughly decent individual who, as the saying goes, ‘let his running do the talking.’

At the Scottish Championships in 1978 Ian was awarded the Crabbie Cup which was awarded annually to the athlete whose performance in the Senior Championships is considered by the General Committee to be the most meritorious – having been won by all the real top stars over the years (Allan Wells, Menzies Campbell, Lachie Stewart, etc – it is a real honour.

![Rosemary%20finish[1]](http://www.scottishdistancerunninghistory.scot/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Rosemary-finish1.jpg)

![Rosemary%20AW[1]](http://www.scottishdistancerunninghistory.scot/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Rosemary-AW1.jpg)

![Rosemary%201970%20800[1]](http://www.scottishdistancerunninghistory.scot/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Rosemary-1970-8001.jpg)

![Rosemary%20at%20Glasgow[1]](http://www.scottishdistancerunninghistory.scot/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Rosemary-at-Glasgow1.jpg)