1986 was a very good year for Scottish athletics in several ways: Despite the many problems associated with it, the Commonwealth Games was a real highpoint; some new stars appeared on the international scene, mainly Tom McKean and Liz Lynch, who had been well-known beforehand but who really came good and launched wonderful international championship careers and the ‘Scotland’s Runner’ magazine appeared for the first time. This magazine that went out of print in 1993 was a great source of information via the results pages obviously but also through the many ‘Upfront’ articles and stories by the editors Alan Campbell, Doug Gillon and Stewart Macintosh with regular contributors Lynda Bain, Fraser Clyne, Bob Holmes, Graeme Smith, Sandy Sutherland, Jim Wilkie and Linda Young. The photographs were first class and the letters pages gave readers an opportunity to contribute to the debate. Everyone was interested in and involved with the sport. It was a real loss when circumstances led to it’s demise. If you want to read the articles in their entirety or re-visit the magazine, just go to Ron Morrison’s website at

http://salroadrunningandcrosscountrymedalists.co.uk/Archive/Scotland’s%20Runner/Scotland’s%20Runner.html

It was natural then, that they should cover the Commonwealth Games in more detail and with more insight than the daily press. I’d like to look at the July to October issues of the magazine and quote from some of the excellent articles on the subject.

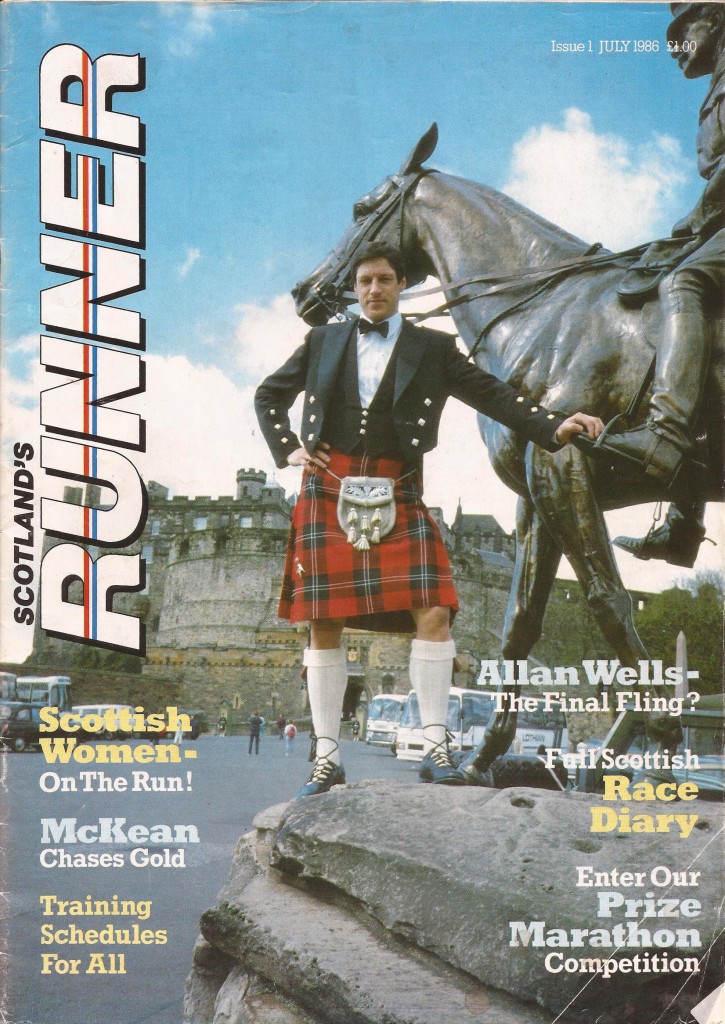

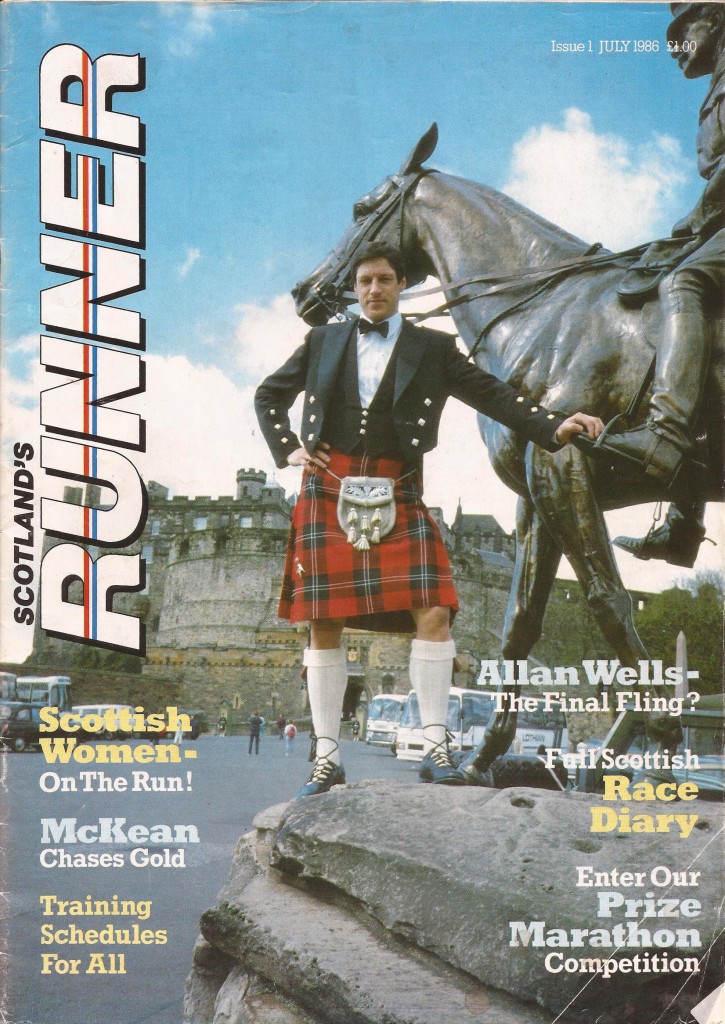

The first issue – cover above – was in July 1986 and among many articles of interest was one by Sandy Sutherland entitled ‘The Shoestring Games’, one by Fraser Clyne on marathon selection difficulties and an interview with Tom MacNab about Allan Wells.

Elsewhere on this website I criticise the low number of athletes chosen to represent their country in the Games but there is an interesting item in the ‘Inside Lane’ page written by Alan Campbell. It reads: “Nobody loves a selector. Every jogger who ever stumbled blistered and leg weary towards a marathon finish thinks he or she can do better. So as the Commonwealth Games selectors brace themselves for the four yearly lashing, let’s set the record straight. The Scottish team’s original allocation of 33 male and 23 female places is smaller in real terms than in 1970. There were 35 men in Edinburgh 16 years ago and 21 women. But since then four events (400m Hurdles, 3000m, 10000m and marathon) have been added to the women’s programme. This allocation is given by the Commonwealth Games Council for Scotland who have consistently refused to increase the figure. That despite the fact that in overall terms Scotland is a stronger athletic nation now than in 1970 (although it does not mean we will win more than the four gold we took then.)

Pressure on the selectors to pre-select, especially in the marathon, was intense. There has to be something wrong with a system that does not get our fastest man on to the start line. But the selectors, with no room for passengers on a tight ship, dared not choose any but certain starters. Allan Wells and Tom McKean are among those over whom serious injury doubts have been raised on the run-in. The fact remains that a domestic Games remains the cheapest opportunity to blood young talent. Lack of funds, always the scapegoat when the Commonwealth Games are held overseas, should be less of a consideration now than ever before. The reality is that in the race to stage the first commercial Games the people who matter most, the competitors, have been left at the post. National Coach David Lease admits that there are good athletes who will not be in the team. That is a disgrace. But it is not the fault of the selectors, or the sponsors and public who have given generously, and who will give more before the curtain goes up on Scotland’s greatest show.”

So the small team was not down to the selectors, but to the Games Council for Scotland. That doesn’t make it much more palatable. The shortage of cash with which to run the show was dealt with later in the magazine in the ‘Up Front’ page. The item read:

“The Commonwealth Games faces a substantial cash crisis after the Government’s snub to a request for financial aid. Attempts to emulate the success of the Los Angeles Olympics by making the 1986 Edinburgh Games the first to be funded entirely by the private sector and public donations have failed. A yawning gap of £1.5 million lies between the Commonwealth Games and financial viability, but on June 2nd the Government refused to make any contribution despite the international kudos which could accrue to such a prestigious international event if it works successfully.

After considerable press speculation, Games chairman Kenneth Borthwick conceded at the end of May that only £12.5 million of the required £14 million has been raised and wrote to the Secretary of State, Malcolm Rifkind, to ask the Government to underwrite the loss. Mr Rifkind turned down the plea and reminded Mr Borthwick that when Edinburgh had bid for the Games, it had been on the basis that there would be no State funding available. He expressed his confidence that the £14 million target would be achieved. Games organisers hope that they have correctly detected a coded message between the lines of the Secretary of State’s reply where he asks to be kept informed of the situation. They harbour hopes that if they fail to clear the £14 million hurdle, some sort of cushion might be provided by Mr Rifkind.

Current sponsors will be approached and asked to consider increasing their contribution and Scots will be asked to make further donations to the public appeal which has had its target adjusted upwards to £2.5 million. Companies who have declined previous request for support and sponsorship will be contacted again and asked to reconsider.”

A sad and rather undignified situation in which to be placed – and the contribution to the discussion by the Secretary of State not at all sympathetic. Sandy Sutherland further through the same issue commented in more detail on the financial aspect in an article entitled “The Shoestring Games” which had the opening paragraph: “Sun and gold medals will make the XIII Commonwealth Games shine in a way that no amount of glossy PR will. And it certainly has not been sunshine and roses for the Games organisers who were faced with some unique problems and a whole new ball game compared to Edinburgh’s so-successful 1970 Games. Yet the cost-conscious 1986 event may yet prove to have done sport a favour – in the long run.” and continued (with a large illustration of the new scoreboard which had been bought second hand from Los Angeles to save money) as follows:

“The 1986 organisers must be praying that we find some new local heroes but with just over a month left before the opening ceremony at Meadowbank, it has to be admitted the portents are not good as over 3000 competitors and officials from up to 50 countries prepare to descend on Edinburgh. Venues, tickets fund-raising, South African rugby tours, Zola Budd, miniscule Scottish athletics teams – these are just some of the topics which have caused rows in the build-up period. The projected Scottish team of 23 women and 33 men is a big let-down for the competitors.

Money however has been the matter which has dominated these first commercial Commonwealth Games. When Scotland was awarded the Games in 1980 in Moscow it was by default – Scotland’s was the only hat in the ring and that somewhat prematurely, as the bid had originally been intended for 1990 or 1994. Edinburgh, the reluctant hosts, gave an assurance that no government money would be required to stage the event as no new facilities would need to be built, hence negligible capital expenditure. But that assurance came back to haunt them, particularly when a new Labour administration was elected in the city. They refused to go ahead with an ambitious project for the velodrome, but in the end however something approaching £400,000 was allocated to dismantling and rebuilding the old cycling venue. But it is much the same style as in 1970 with new wood, but still open to the elements with all the attendant risks should rain fall during the Games.

The city have also resurfaced the Meadowbank athletics track and spruced up the old stadium. A huge new scoreboard dominates the West end (but perhaps not big enough to shut out the awful prevailing wind?) and a photo-finish box in the stand shuts out at least 150 seats. Improvements totalling £4 million were budgeted for by the city, including some at the Royal Commonwealth pool, venue for the swimming events, and Balgreen, where a lot of bowls will be played and talked about. But that expenditure pales beside the organisational budget which at the time of writing stands at £14.1 million. Compared to what it might have been, that is quite small. The budget in Brisbane in 1982 was £17 million and, allowing for up to 25% increase in competitors, that figure might well have reached £28 million. Instead that has been halved.

“That is a fine achievement,” says Robin Parry, managing director of the consortium of accountants, Arthur Young, and publicity agency, Crawford Halls, charged with the task of raising the bulk of the funds, through advertising, sponsorship and licensing and other deals. Will they achieve their target?

“It’s finely balanced,” says Parry whose group will be fund-raising right up to the Games. “In particular, arena advertising tends to go at the last moment, but we have already definitely raised over £13 million and I’m optimistic of closing the gap.” The consortium’s conservative projection, from their various sources, including hospitality suites at the main arenas, is £8.5 million while the public appeal is expected to raise £1.5 million. TV rights – £500,000; tickets – £1.1 million; and programme sales, after sales of equipment and other items – £600,000; while £1 million was raised in early sponsorship. The appeal includes the Lottery, which could prove quite money spinner, and the “McCommonwealth campaign” which has had a lukewarm response in its initial stages at least. The Commonwealth Games book and the special £2 coin are two of the items which come under Parry’s remit and are two of the hardest to assess in terms of return.

But tickets look like exceeding their target and, with the main sessions at athletics and swimming sold out within a few days of going on sale for postal applications last September, there could be quite a black market for these. Part of the problem for the organisers has been that they did not know how many seats were actually going to be available because the stadium capacity had not been settled due to the Popplewell Report on crowd safety and the extra room taken by hospitality units. It looks as if, despite the extra terracing, the Meadowbank capacity will be approximately 22,000 compared with well over 30,000 in 1970 when scaffolding doubled the norm. Sadly a priority ticket scheme intended for the real athletics fans, which would have given athletics clubs and others a month’s advantage over the general public, was so mis-handled that the dates merged. That is just another example of how the people in the sport appear to have been neglected in these Games. So in the end who will benefit?

Certainly the Games themselves. the inflationary spiral which has gone on through Christchurch, 1974, Edmonton, 1978, and Brisbane has been broken, and Edinburgh in particular because of the massive television exposure and the income from tourism (which has been estimated at £50 million). Certainly sport in general though rowing, back in the Games for the first time since 1958, with new purpose-built facilities at Strathclyde Park, could point to more obvious benefits than swimming or tack and field which have been short-changed on facilities (no warm-up pool or track for example) and competitors. But short-changed or not, track and field will be the centre-piece and showpiece of the Games, and the making or breaking of them. And our athletes have destiny in their hands.”

It’s a very interesting article and looking back Sandy’s comments towards the end of the penultimate paragraph about priority ticket schemes, is thought provoking. In the collection of club memorabilia that I inherited from James P Shields is a letter from the organising committee of the London Olympics of 1948 asking of any of our club members would like tickets for the event. nearer home, all clubs in Scotland were asked how many tickets they would like, where in the arena they were for and for what events. Here again is the idea that those who are involved in any sport should have priority in the availability of tickets is mentioned. It is worse than just a shame that this idea has been abandoned in favour of mass, elbows out, scramble for tickets at Olympic and Commonwealth Games.

For now I will hold back from re-printing Fraser Clyne’s article – sections of it will appear elsewhere soon – on marathon selection but will say that his conclusion was that “the 1986 Commonwealth Games marathon team should have been picked by no later than the end of 1985.”

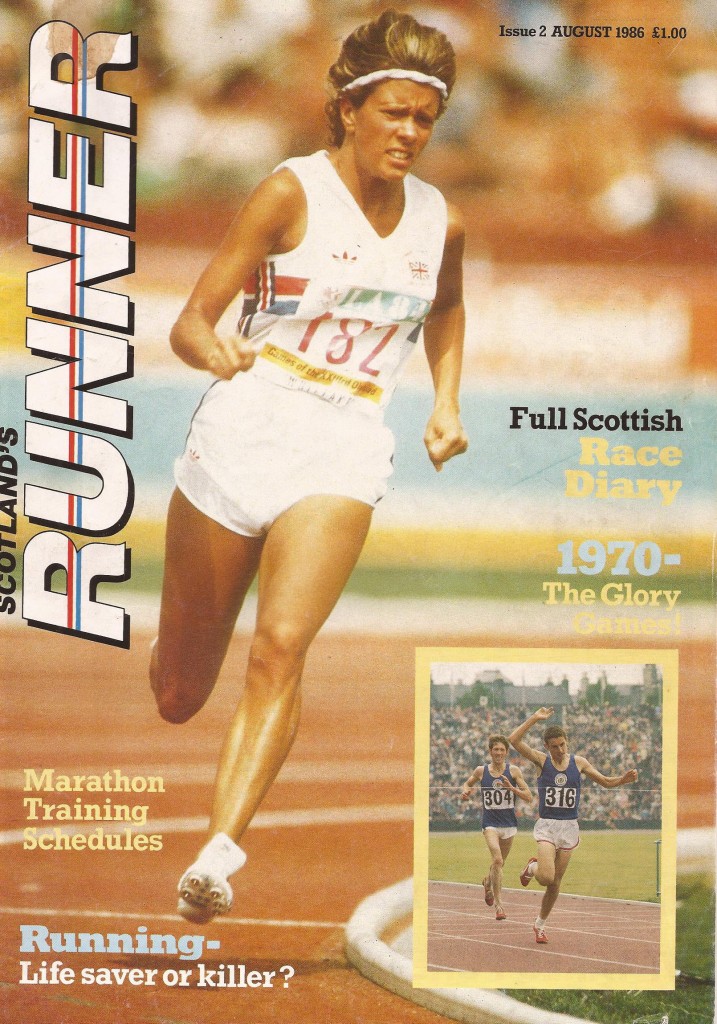

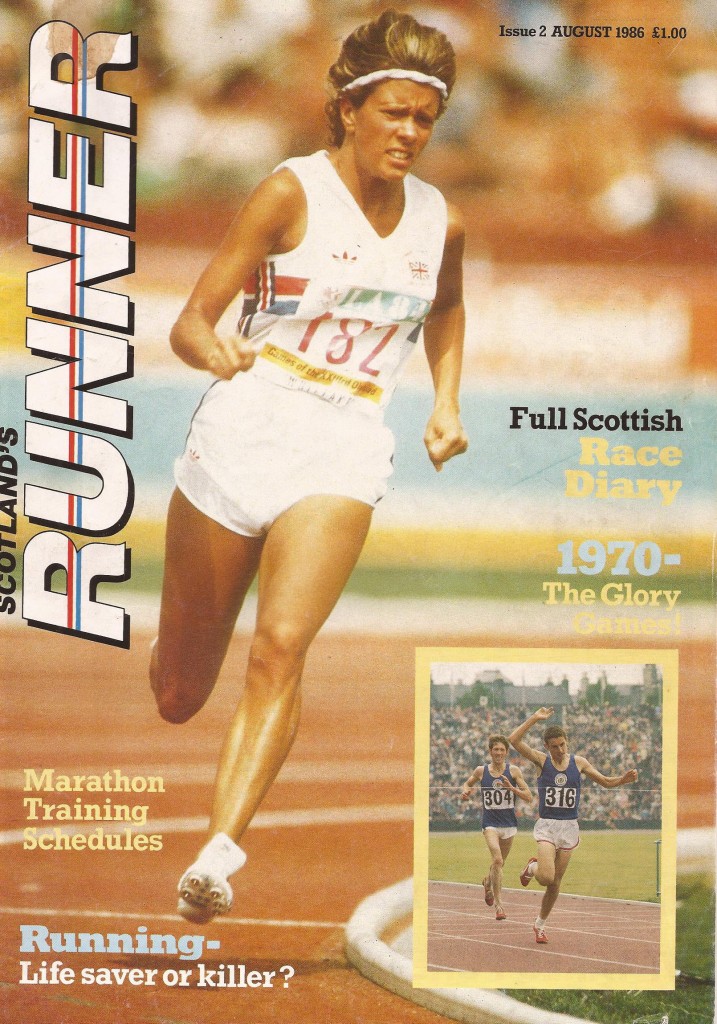

The above picture features Sandra Whittaker the quite outstanding sprinter, coached by Ian Robertson, who was one of the very best Scottish runners ever. It is most unfortunate, to put it mildly that she has been virtually ignored in recent years. A woman who in the Los Angeles Olympics set personal bests in the heats, and in the quarter-final has to be very special. She is still the only Scotswoman inside 23 seconds for the 200m. With talents like hers and her training partners and the Edinburgh group of the same period, there should surely be some website with profiles or tributes to our sprinters. However, in the second issue of “Scotland’s Runner”, the middle pages full-colour spread was an article by Doug Gillon which took a look back at 1970 and had what was called an optimistic look ahead. But first, in the very first page of the magazine was Alan Campbell’s ‘Inside Lane’ page with the dreaded news that many had anticipated but which no one wanted to hear: the boycott was now on. The article read:

“On July 9th, the darkest cloud hanging over the success of the Commonwealth Games finally burst over mountainous political pressure. Nigeria and Ghana announced their withdrawal over Mrs Thatcher’s attitude towards South African sanctions. Just 24 hours earlier, new Games trouble-shooter, Mr Bryan Cowgill, had felt justified in announcing a record Games entry including a full African participation led by … Nigeria. Yet no sooner were we digesting the good news in our morning newspapers than our kippers and toast were upset by the boycott announcement. The news came just in time for Scotland’s Runner’s final deadline for this issue. we cannot therefore give an in-depth analysis of the ramifications and repercussions. By the time you read this, any amount of political machinations – ranging from a full Afro-Asian-Caribbean boycott to a compromise salvaged from Sir Geoffrey Howe’s seemingly ill-starred trip to Southern Africa will have decided the fate of the Games. ……

The sanctimonious claptrap mouthed by Mrs Thatcher on the morality of sanctions against South Africa had already turned enough white stomachs – including ours – before Nigeria and Ghana took their precipitous decisions. In the light of the worsening political climate which dwarf the problems of the Games, a far more delicate hand than Mrs Thatcher is capable of playing was called for if the original boycott threat was to be finessed. Before returning to the subject of the boycott however let us not pass over the, now admittedly parochial, commercial and administrative problems which have bedevilled this Commonwealth festival from the outset.

After 18 months of rumour, evasion and a permanent smokescreen of optimism from the Games organisers, the truth emerged. The Games were on the brink of cancellation; the limited company, Commonwealth Games ’86 Ltd, was in danger if trading illegally, and Scotland would have become an international laughing stock. Part of the blame must lie in Canning House, the Games HQ, where a bewildering series of some 40 committees was spawned under the muddled leadership of Games chairman Ken Borthwick, a former Conservative Lord Provost of Edinburgh and a newsagent and tobacconist shop proprietor. Political wrangles with a new left-wing Edinburgh District Council administration did not give confidence that the organisation of the Games was progressing smoothly. The Government could and should have done much more, but their dogmatic commitment to the market economy blinded ministers to the contribution that a successful Games could bring to the future standing of Scotland and the UK.

To be fair, it had been made clear at the outset that these would have to be the Commonwealth’s first “Commercial Games,” but when the fund-raising consortium got tantalisingly near the £14 million target it was petty of Malcolm Rifkind. the Secretary of State for Scotland, to refuse to fight in Cabinet for the funds that would have bridged the gap and given his home city and Scotland an unbeatable opportunity to perform on the world stage. It would have been a very small amount to pay for the potential return in terms of future tourism and commercial interest.

Then the cavalry came riding over the hill. Robert Maxwell, publisher of Mirror group Newspapers, had (with nothing more binding than a handshake) apparently won control of the Games, unseated Ken Borthwick as chairman, and in the process won himself enormous publicity. But when the cavalry comes to the rescue they are supposed to fly in with a life-saving charge, not stand on the hill-top trumpeting for reinforcements which are still some way over the horizon. In return for his dramatic winning of the Games Maxwell seems to have offered nothing more than a promise to do three things: to campaign vigorously for further injections of commercial money, to explore advertising and sponsorship opportunities which the Games organisers had missed, and to demand that the Government throws some cash into the pot.

Major sponsors such as Guinness, who have put money rather than hot air, into the Games must wonder whether they have got the full return on their investments when one of the most formidable personal publicity machines in the UK won the top seat so cheaply. As one Scottish newspaper pointed out, it was as if the annual newspaper ‘silly season’ had started early this year; indeed if it was not for the fact that these indignities are being inflicted on our country and our sport it would be all rather comical. ….

Returning to the boycott threat, having apportioned blame in all directions for the commercial shambles, we would like to at least applaud the Scottish Commonwealth Games Council for having tried its damnedest to keep the Games intact (and indeed Edinburgh District Council, although their methods at last year’s Dairy Crest Games were less than diplomatic). The Games Council cannot be held responsible for the selfish attitudes of rugby administrators and players determined to flaunt the Gleneagles agreement on sporting links with South Africa now could they prevent the Daily Mail and the Home Office conspiring to polarise Commonwealth opinion over their handling of the Zola Budd affair. Whatever the situation on July 24th, Scotland’s Runner can only join sports lovers everywhere in hoping that the merchants and politicians finally got their act together in time to salvage the Games.”

This is not the entire article but he doesn’t mess around – he says what he thinks: and what he thought was endorsed by most of the Scottish sporting public. He mentions the Gleneagles Agreement had been signed at Gleneagles in 1977 and discouraged sporting contact with teams from South Africa because of their apartheid policies – read about it at this wikipedia link http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gleneagles_Agreement As far as the boycott of the Games by the African teams is concerned, it was a great deal to do with the Thatcher government’s attitude, Philly.com said frankly in 1986: “Thatcher is virtually alone in the Commonwealth in arguing that sanctions against South Africa will not work, but in October she persuaded the other heads of Commonwealth governments to appoint a delegation to find ways to open a dialogue between the South African government and black nationalist leaders.” Despite the agreement, England’s rugby team toured South Africa in 1984 although the Lion’s tour in 1986 was cancelled. The Edinburgh Games Committee took a very public stand against the English tour but to no avail. The whole story can be found at http://www.bl.uk/sportandsociety/exploresocsci/politics/articles/boycotts.pdf .

Doug Gillon’s major article in the middle of the second issue of the magazine. Starting with a look back at 1970 when Scottish chances of any gold medals were scoffed at (other than McCafferty – if we’re lucky!) Looking ahead, Peter Matthews (ITV commentator) said we would get two – silver for Parsons in the High Jump and bronze for Liz in the 10000m. Before looking at the prospects for 1986, he retells the story of an Englishman who wrote off Lachie’s victory over Ron Clarke in the 10000m by saying that a champion should win like a champion – from the front. Jim Alder came back at him. “England’s great athletics hero Chris Chataway in his epic duel with Vladimir Kuts had led for 20 yards – the last 20!” Doug says, in an article that is still worth reading, “There is certainly no lack of ambition. The American philosophy of ‘First’s first, second’s nowhere!” alternatively expressed by “winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing” is a sentiment that many home athletes share. They just are not as obtrusive about it as the Yanks. But on current ranking, at the time of going to press, the reality is that not one Scot tops the Commonwealth lists in his or her event. But the impact of national fervour cannot be underestimated. I believe that Scotland has genuine medal prospects in Tom McKean (800m), Allister Hutton (10000m), John Graham (marathon), Geoff Parsons (High Jump) and the 4 x 400m relay provided the squad can get their act together. I also believe that the hopes of gold are greater with the women. Nobody should underestimate the talent of Yvonne Murray in the 1500m and more particularly, the 3000m, of Liz Lynch in the 3000m and 10000m, or of Lorna Irving in the marathon. And Chris Whittingham has already carved three seconds from her 1500m personal best this year, running in Oslo, where she clocked 4:06.24, a time inside the Games record.

It will hopefully be third time lucky for her family. Her twin, Evelyn, competed in 1974 at Christchurch, both of them were in Edmonton where Chris placed fourth in the 1500m. In addition Christine’s husband Mike was edged out of the medals in the 400 metres hurdles in Brisbane. There are several other events with lesser medal prospects and national and native records will fall regularly.” The article continues with an appraisal of the Games as a whole.

The magazine contained other articles relevant to the Games – an interview by Bob Holmes with Geoff Parsons (who was to go on to win silver), several items in the Up Front section including one on the Guinness ‘Commonwealth Friendship Scroll’ travelling round the Commonwealth.

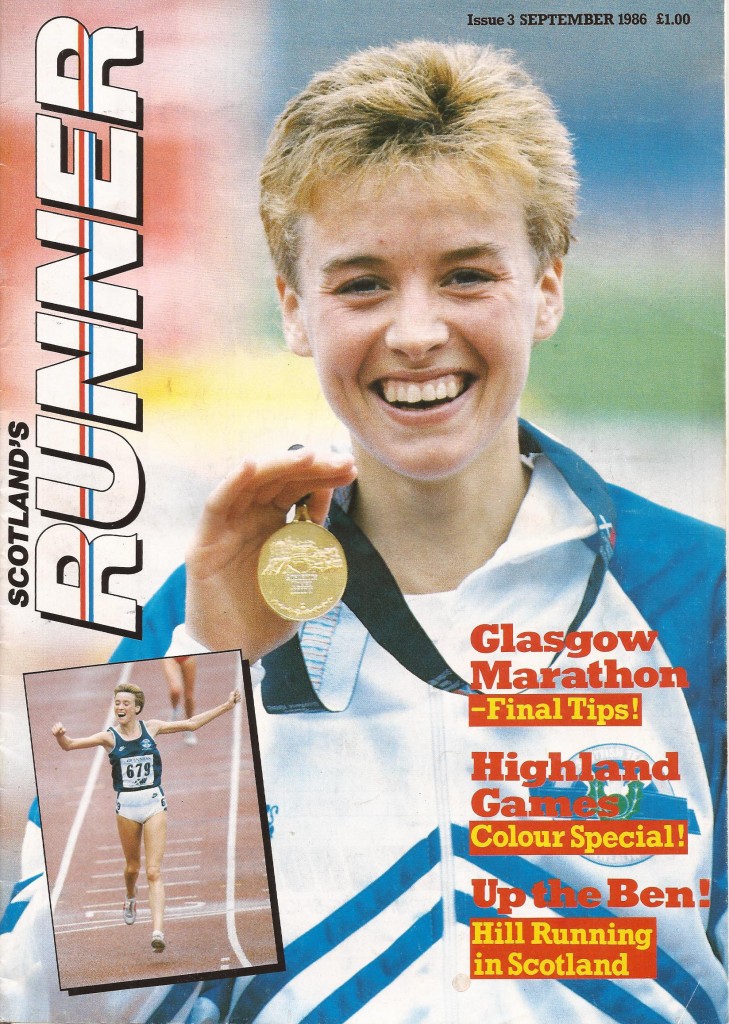

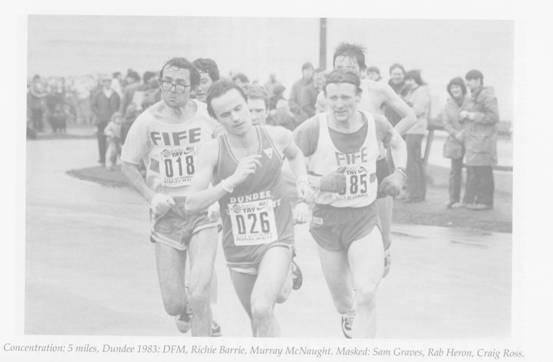

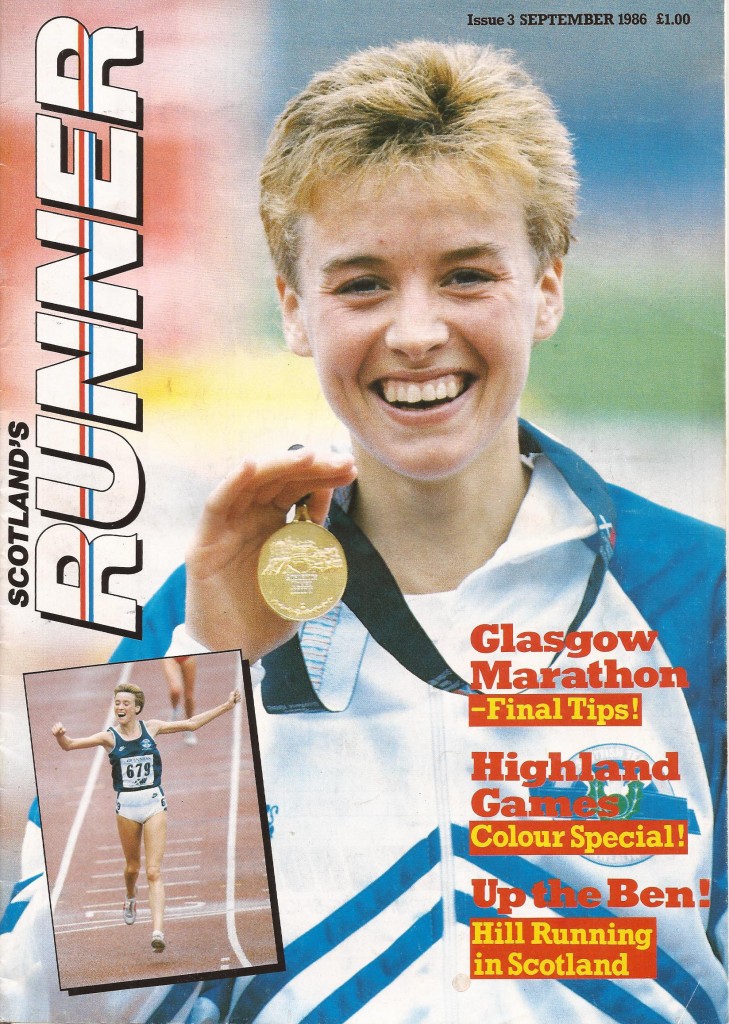

The cover picture of Issue Number Three, September 1986, tells the story! The men’s 10000m gold medal of 1970 had been equalled by the women’s 10000m gold in 1986. By the time the magazine hit the streets, the Games were over but the magic of Liz’s medal was still in the air and the delightful picture on the cover above just summed up everyone’s delight at the result. Doug was given the two middle pages to ‘Report On The Games’ with another superb photograph of the end of the women’s 200 metres showing the first three in full flight. Doug wrote:

” …. Jake Young, a teacher at Edinburgh Academy identified the talent of sprinter Jamie Henderson and commendably realised there were people better equipped than he to develop the boy’s potential. In less than a year under Bob Inglis’s care, Henderson had won gold and bronze at the World Junior Championships and bronze in the Commonwealth Games relay.

In cold statistics there were many who did not live up to expectation in Edinburgh. Injury in some cases saw to that. Janice Neilson never competed at all and Lindsey McDonald appeared to be limping during her warm-up and clearly competed in pain. Moira McBeath from Thurso who finished seventh in the final of the semi-final of the 400m hurdles is pregnant. Our three men’s 400m hurdlers all failed to match their best. Neither Allister Hutton nor Nat Muir came anywhere near threatening the Scottish native best for 10000m or 5000m which has stood since the 1970 Commonwealth Games, despite having run well inside these marks. The long jump of 7.51m that gave Dave Walker sixth place in 1970 was one centimetre further than sixth place in 1986; the heptathlon long jump of 6.39m by Moira Walls in 1970 would have won her the bronze medal in the individual event this time; and the Scottish women’s relay squad have still not run any faster than the 45.2 seconds which an Edinburgh Southern Harriers squad achieved to win the WAAA title in 1970.

Worse, the boycott would almost certainly have stopped us from winning at least two of the six medals won. But athletes can only beat those who turn up on the day. Sandra Whittaker surpassed expectation in becoming the first Scottish woman ever to win a Commonwealth sprint medal, maintaining her style spectacularly over the final 20 metres when it counted. The men’s relay squad succeeded against the odds. Cameron Sharp, nursing himself round with an excruciating back and leg injury after sacrificing his personal aspirations in the 200m to do so. And George McCallum tore his right hamstring yards before the vital final takeover to Elliott Bunney.

The highlight was of course Liz Lynch’s stunning 10000m victory. It was a great gamble for the Dundee woman who was ranked top of the 3000m starters. Had she known the 3000m would have been a straight final, she would have attempted the double. The girl from Whitfield in Dundee was another who had a haphazard introduction to the sport. She went with a group of friends to Dundee Hawkhill Harriers and left almost immediately. It was only later that she returned. It was the late Harry Bennett who converted Liz from a 100/200 runner to a distance athlete before she left to study in the USA at a junior college and then at Alabama. Yvonne Murray, who settled for bronze but made a brave bid for gold in the 3000m, was spotted playing hockey by her biology teacher, Bill Gentleman. Tom McKean however has had a more normal progress in the sport, a member of Bellshill YMCA since shortly after his eleventh birthday, and nursed delicately by coach Tommy Boyle. His silver medal behind Steve Cram was a national record and bettered a native one that had stood to Mike McLean, chairman of the selection committee for the Games since 1970. Geoff Parsons fell one short of his ambition to win gold but equalled his British outdoor record to do so.

At this time last year, Jamie Henderson was pulling on an Edinburgh Academy cricket sweater. The Games were something that would be happening in his native city the following year. He might buy a ticket or two and go and watch. Or he might not. Instead the sweater was resurrected like a prop from the wardrobe room of Chariots of Fire, and Henderson wore it on his way to the starting blocks for the men’s 100m final at Meadowbank last month when he became the youngest man to contest a Commonwealth sprint final since the 17 year old Dan Quarrier struck gold in the capital 16 years before. Henderson wore it again when he Groge McCallum, Cameron Sharp and Elliott Bunney came out to take the relay bronze. A year is a short time in athletics, but the progress made by Henderson in that time is perhaps the most heartening thing to emerge from the Commonwealth Games. And that is not to minimise the stunning success of the delightfully unspoiled Liz Lynch. For the emergence of the Edinburgh teenager in so short a space of time is proof that the basic natural resource of the sport is flourishing in Scotland. But we must have more input. Otherwise these resources will be burned and wasted like a puff of spent tobacco.”

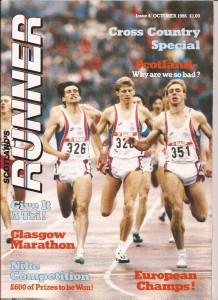

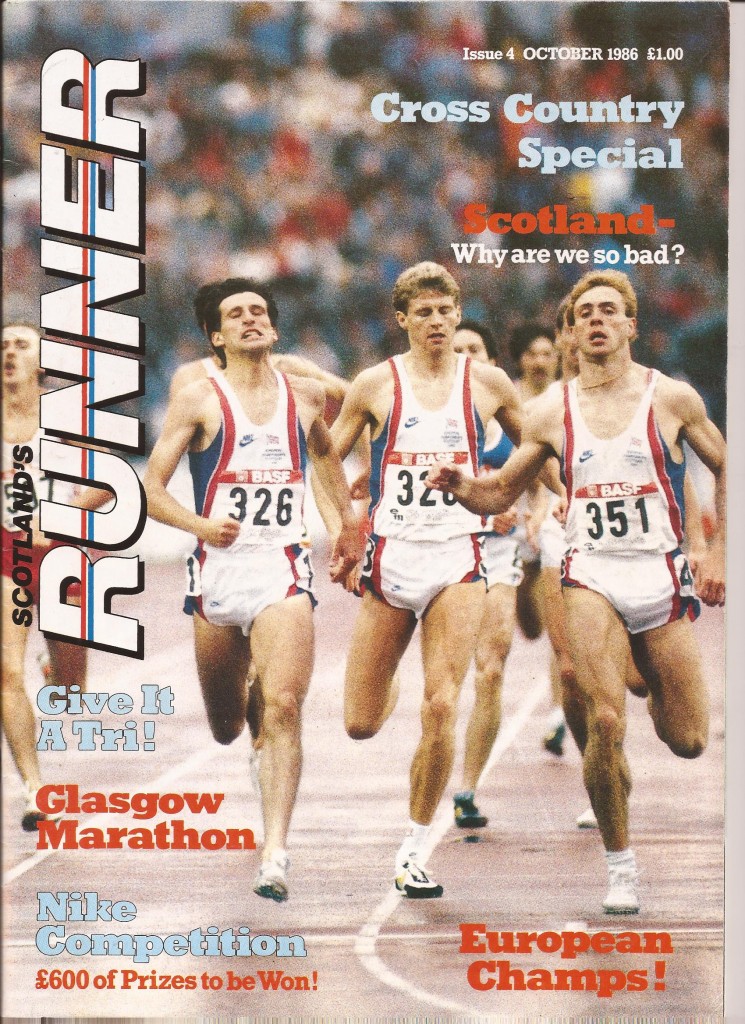

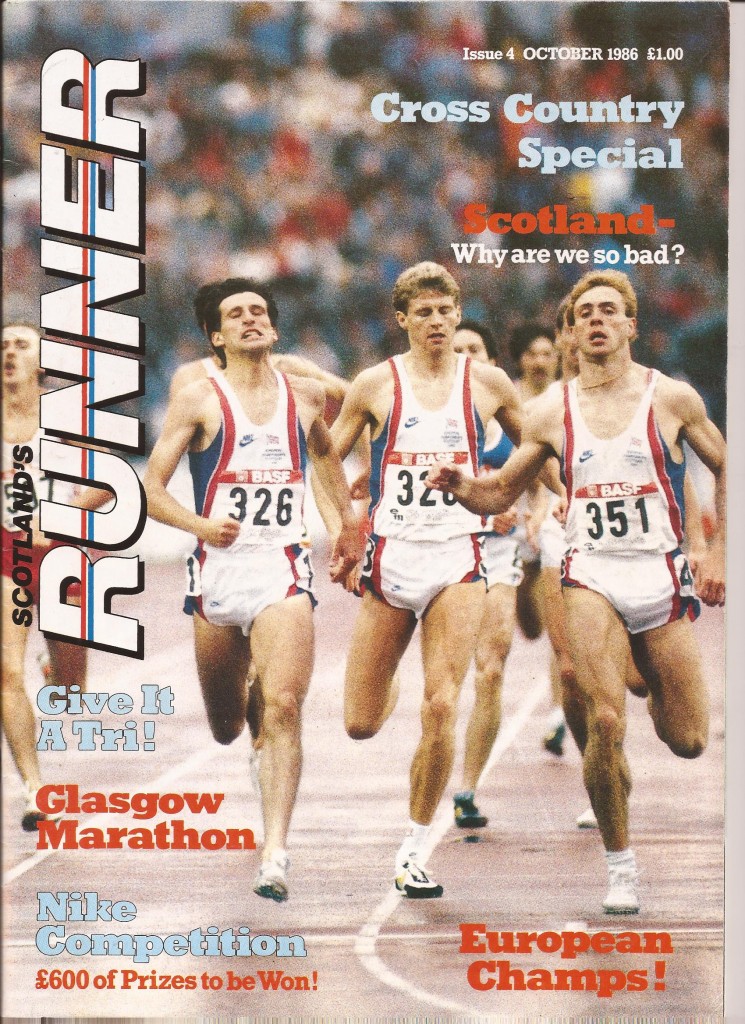

That is most of Doug’s article and it was the only major one in “Scotland’s Runner” that month. The following month brought an article by John Anderson under the title of “Why Are We So Bad?” and a report by Doug Gillon on another event that certainly affected the Commonwealth Games – the European Championships later that year.

John’s article read:

” … we have a cultural heritage second to none, one which promotes the twin elements of dedication and passion. The Scottish tradition is to learn well and fight hard to achieve. We must harness that.

POTENTIAL

Clubs come in all shapes and sizes, some well organised and well resourced others which barely survive from year to year. Some clubs have a large variety of facilities and can provide their members with a complete range of opportunities, coaching and competition, supported by an excellent organisation. Such clubs however are limited, largely through no fault of the club but either because they are geographically isolated, or by the nature of their limited resources they are unable to provide comprehensive opportunity to those in their area. It is important to recognise the contribution made by schools. The Scottish athletic tradition has been to a large extent built on the excellent network developed at this level. But this marvellous tradition is in jeopardy as teachers consider whether they can afford to continue. If the school involvement dimishes, this will pose further problems for clubs and the development of the sport.

But however many clubs there are, and no matter how well equipped and funded, they cannot function without the voluntary club official. Like the clubs they come in all shapes and sizes, but have in common a desire to give their time freely in order to ensure that others enjoy the full range of opportunities in athletics. These people must fulfil many functions. They have to be first-class administrators, able to deal with the secretarial and financial aspects of the organisation, and they certainly have to deal with fund-raising since most clubs usually exist on a hand-to-mouth basis at best. There also have to be coaches to advise the young athletes and there must be conpetitions organised, and the structure to provide the numerous judges, timekeepers and other officials. So, on the plus side, Scotland has a multitude of willing voluntary helpers, the backbone of athletics without whom the sport would cease to exist, or at least would exist in a very limited form. We also of course have outstanding performers who have emerged to put a little dash of colour on Scottish athletics. In addition to the one or two jewels in the crown is the very substance of athletics, the performers. Some argue that athletics is about providing for these people rather than for the elite, but the argument of course is specious because all athletes are part of the sport. The top encourages the bottom. Aspiration and achievement are recognised throughout the sport and therefore those who achieve the highest levels act as a stimulus to those whose performance and talent are not at that level. It is important to identify at the outset that the pursuit of better performance is the driving force within athletics. One cannot just take part.

If it is accepted that all athletes are aspiring to improve and that officials are there to help bring this to fruition, we have to look at whether the existing structure achieves these ends. The sport, including cross-country and road running, is too fragmented for effective management structure. Any management consultant would feel that the ability to implement new initiatives would be restricted in view of the small population and large land area. The existing structure does not ensure that those who live in the more outlandish places are given an equal opportunity with those in the central belt. There are many self evident criticisms which might be directed in terms of management organisation and structure given the current framework, but suffice to say that the current structure is a nonsense and cannot achieve even a small part of what it sets out to do. We need organisation and radical change.

The problem of scale outside the central belt means that athletes are not given equal opportunity – or even an adequate opportunity – to take part in club athletics or competitions. This is compounded by the fact that very few clubs are able to offer a full range of facilities in terms of road running, cross-country and all the various forms of athletics – throwing, jumping, pole vault, etc. In many cases they even lack the required level of coaching expertise. It is therefore necessary to find ways in which the resources might be used more effectively and efficiently. In some if not all parts of Scotland the competition structure leaves a good deal to be desired , Certainly there are many very good competitions available. These have grown over the past few years and are a credit to those who organise them. But they are centred largely on the central belt and tend to leave others in isolation. There are different modes of competition, the lifeblood of the sport, which might be brought into such areas to the benefit of the raising of standards.

Competition is based on the existing club set-up but this is clearly inadequate. What we must do now is build on that structure which has stood the test of time. The older clubs must pool their resources, building an area structure on top, evolve the concept of more wide-ranging competition. This could take the form of inter-area matches in throws, jumps and pole vault, others in sprints and hurdles, others still in the middle distance races. It should not be beyond the wit of man to devise this. Scots traditionally reflect great national pride. It is in evidence in all the national sports events when the Scottish people demonstrate their loyalty and pride in their heritage. Sadly this very often is not reflected in the way in which our organisations function. It may well be suggested that there is no really strong national feeling or sense of responsibility in Scottish athletics, that the sport is too parochial. that it sells itself almost exclusively to individual clubs and those within these clubs concern themselves with ‘The Club’ rather than examining how the whole national scene can be improved.

We must examine the sport’s funding in Scotland and different methods of financing must be promoted and developed. Certainly if further development is to come then the whole area of sponsorship and support from local authorities, quite apart from national level involvement must be scrutinised. As a Glaswegian I am ashamed to note that in spite of being one of the largest areas of population, Glasgow has languished behind not only Edinburgh, but many other smaller places between Glasgow and Edinburgh in its provision of facilities. It borders on a national disgrace that Glasgow has only recently acquired one synthetic track for its entire population – this from a city which promotes itself as being ‘miles better.’ One track is inadequate and even the new Kelvin Hall project will only scratch the surface of the lack of indoor facilities. Until that is resolved nationwide, Scotland’s adverse weather conditions will certainly limit the development of technical events.

Tradition is a two edged sword. It can be a positive or a negative weapon. In Scotland the young are taught that the club is the focus of all activity, superseding all others. By definition all else falls by the wayside. Youngsters are taught to be hostile to other clubs, to succeed at the expense of others. What is taught is negative. We should be sharing our limited resources. Very, very seldom do you hear of clubs sharing their knowledge, expertise or facilities or assisting other clubs. All the clubs in the Edinburgh area, for example, could be pooling their resources. There would be enough coaches to go round and a scouting system could be developed to tap into the schools. Instead they are too frightened of the possibility of poaching. The clubs are too selfish. The questions they must ask themselves are, “Is the sport bigger than the club? Do they care enough about the sport they profess to believe in to change things?”

The allegation of Scottish small-mindedness is one that has to be looked at. We Scots have to bury our parochial attitudes in the interests of national development.

SOLUTIONS

The control, administration and management of Scottish athletics must be re-structured and reorganised. A diverse and fragmented administrative structure leads to inefficiency and ineffectiveness. A single administrative office was a step forward but one body for a country the size and population of Scotland is the answer. The form that body should take and the responsibilities it should have are matters which can be resolved with goodwill on all sides. This questions the motives of the adults who run Scottish athletics. It is the officials, who put in many hours of effort, who actually control the sport. The athletes themselves, although capable of decisions, are motivated by participation rather than politics, and it will always be thus. So the responsibility for the future lies with those officials, and they now carry an onerous responsibility. No doubt the vast majority of national officials come altruistically into the sport, but over the years that altruism becomes blunted. The fragmented nature of Scottish athletics is perpetuated by misguided individuals reinforcing the separate entities of the sport, men’s and women’s track, men’s and women’s cross-country. There is little to suggest in recent years these incumbents have made any effort to bring the organisations together for the good of the athletes and the sport. Instead they seem intent on retaining their power.

They have the power to run the sport more effectively, but that will require sacrifices from them. The tendency is to focus attention on their own club’s particular role. What is needed is a magnanimity of spirit and attitude in the interest of the sport nationally. These people must look beyond their own role and examine the contribution which could be made if they took a less parochial stance. The leaders of Scottish athletics must do precisely that … lead Scotland into building a new structure, one more efficient and effective, one able to respond rapidly to the needs and demands of the athletes. We should be riding on the high of the enthusiasm generated by the Commonwealth Games and the success Britain achieved at the European Championships at Stuttgart. We owe it to the new generation of Scottish athletes.”

That’s John’s article and it makes interesting reading. At the time it was written, Scottish athletics was governed by the SAAA, SWAAA, SCCU and SWCCU – he was one of the first to propose the amalgamation of the four bodies into the Scottish Athletics Federation, and as usual with John, the priority was always the good of the competitors. A lot of what he has said about competition and clubs away from the central belt has also come to pass.