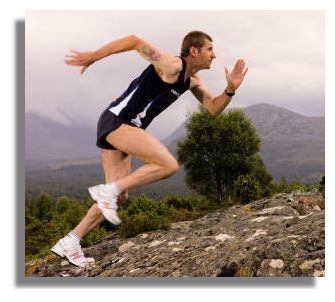

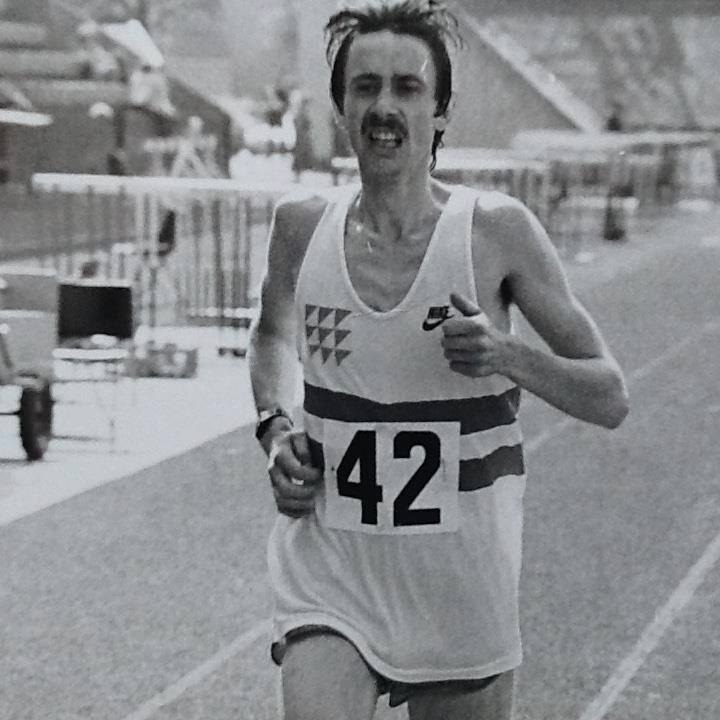

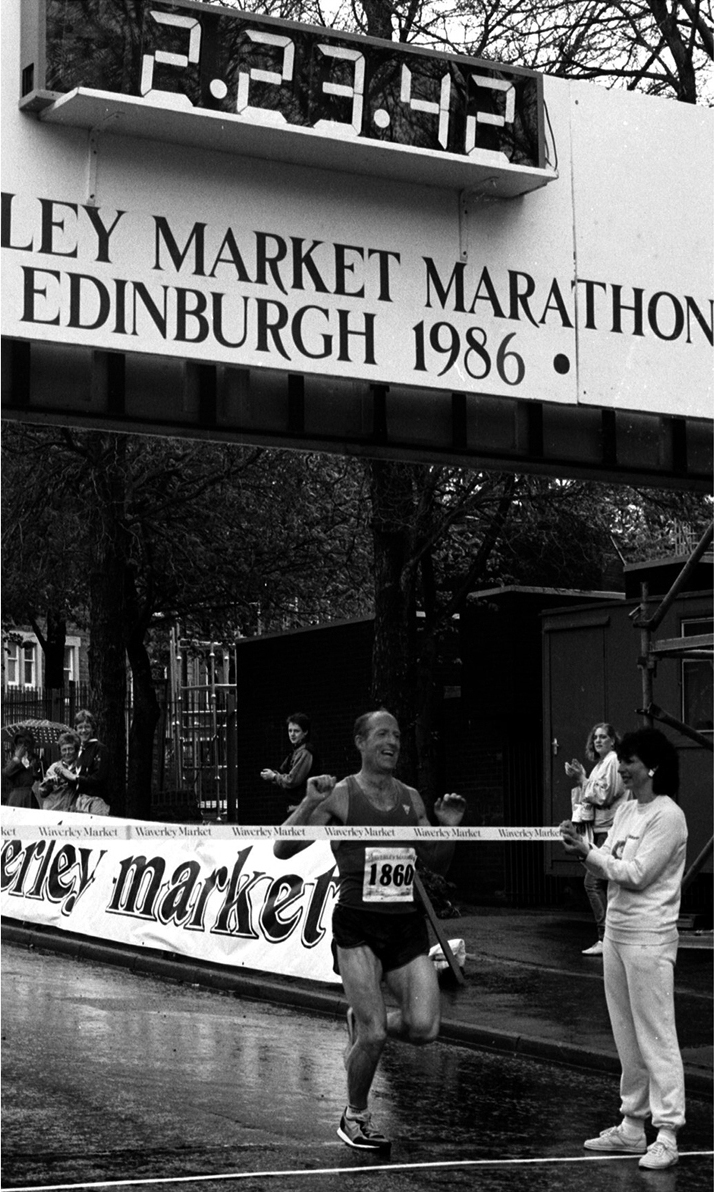

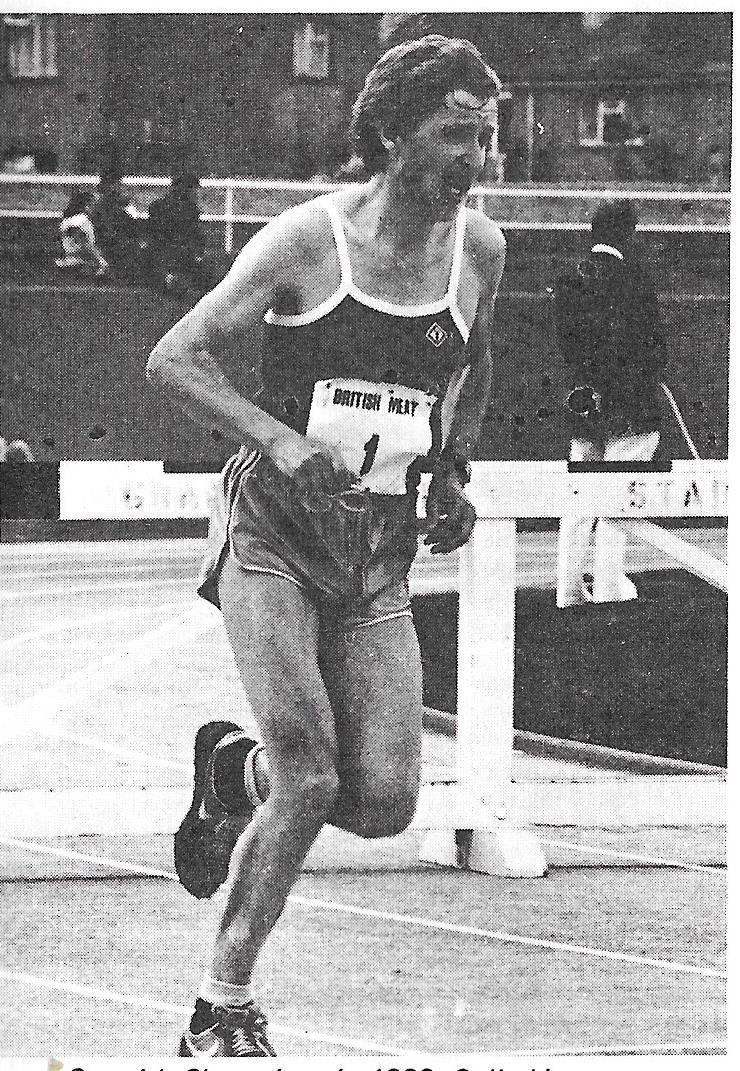

Simon Pride celebrates after winning the Belfast Marathon

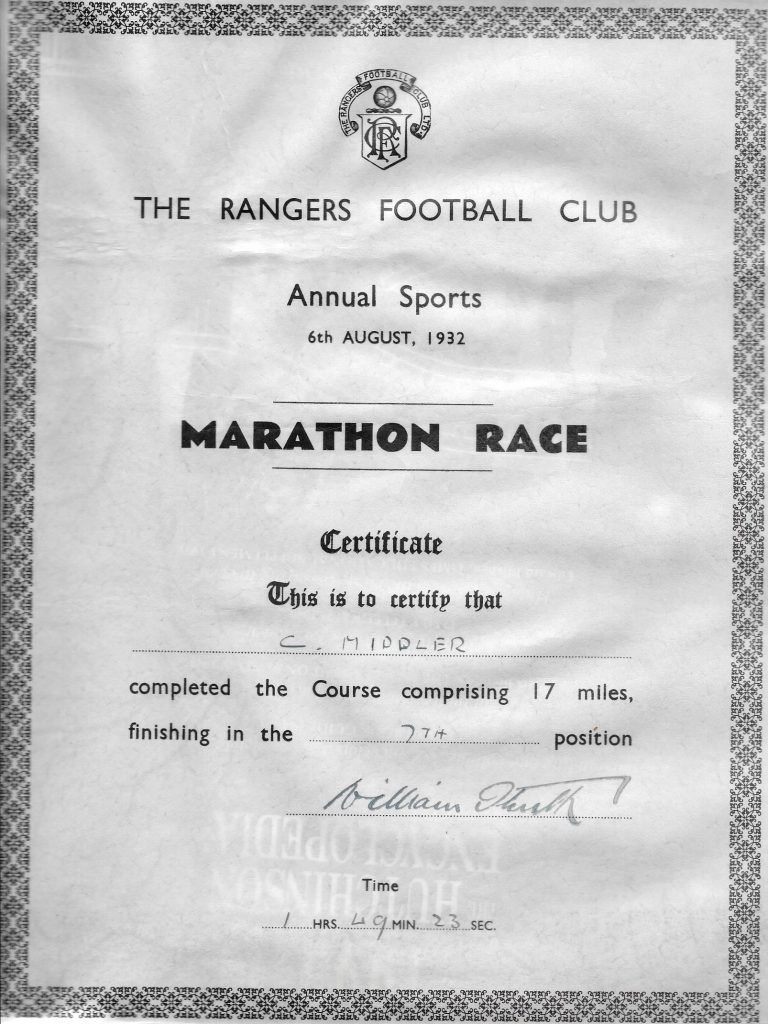

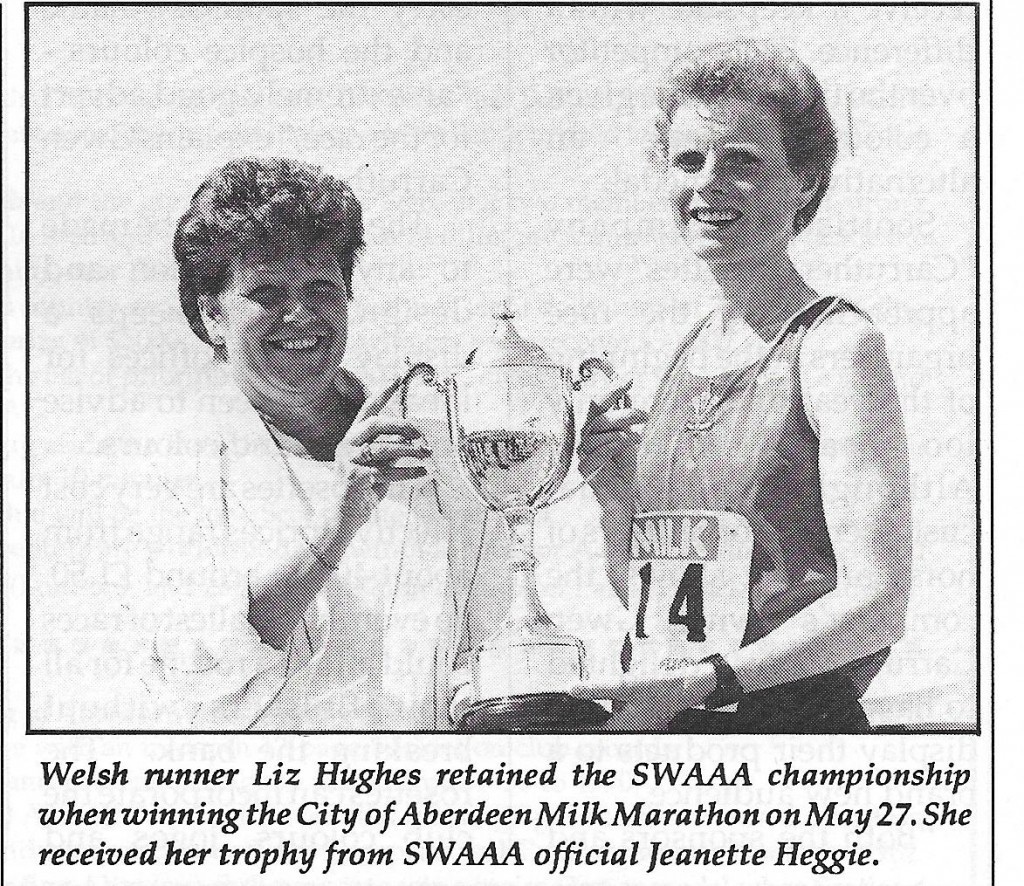

The Scottish Men’s Marathon Championship in the 2000s was dominated by two runners; one was Simon Pride (2000, 2001, 2004 and 2006) and the other was Jamie Reid (2002, 2003 and 2007). Amongst the winners of the Women’s title, Kate Jenkins, the Champion in 1997 and 2000, won again in 2003 and 2007. However Shona Crombie-Hicks and Ros Alexander (2005), Toni McIntosh (2009) and Trudi Thomson (2001) produced the fastest times during the decade, although Megan Crawford and Jennifer Emsley also ran well during 2013-2015).

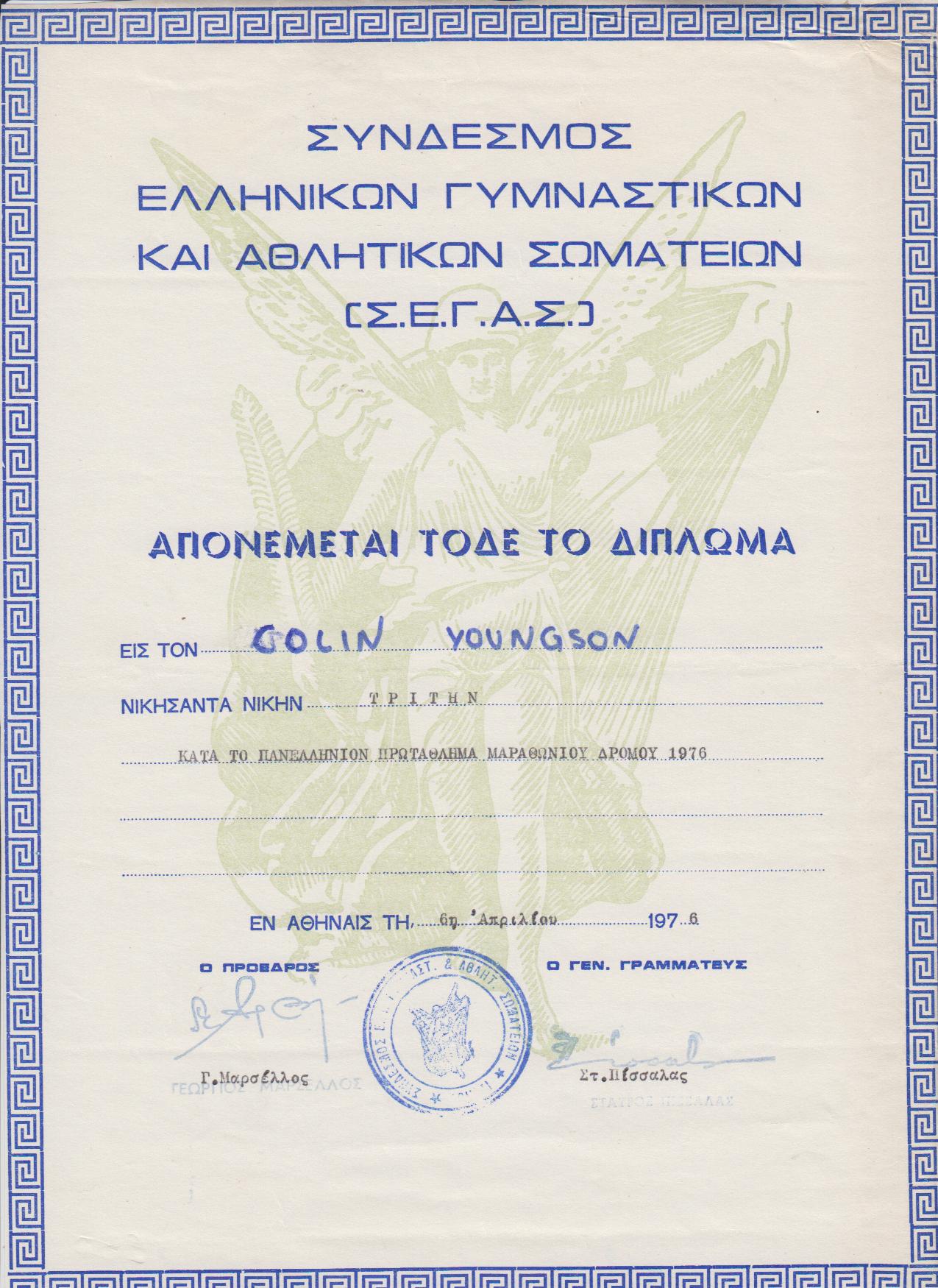

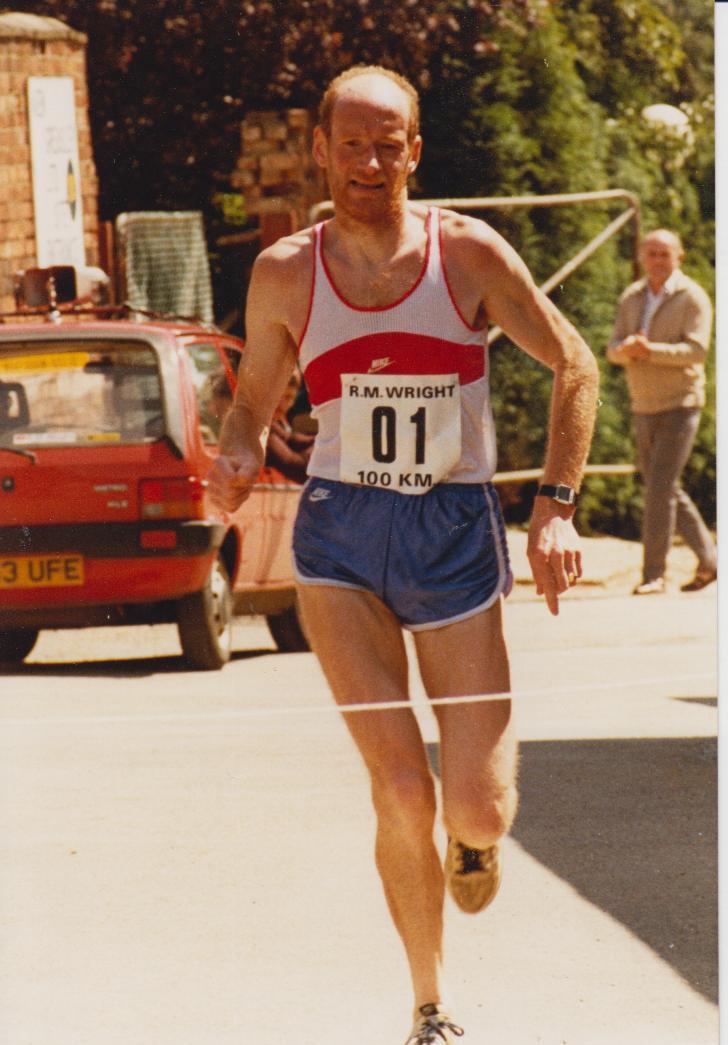

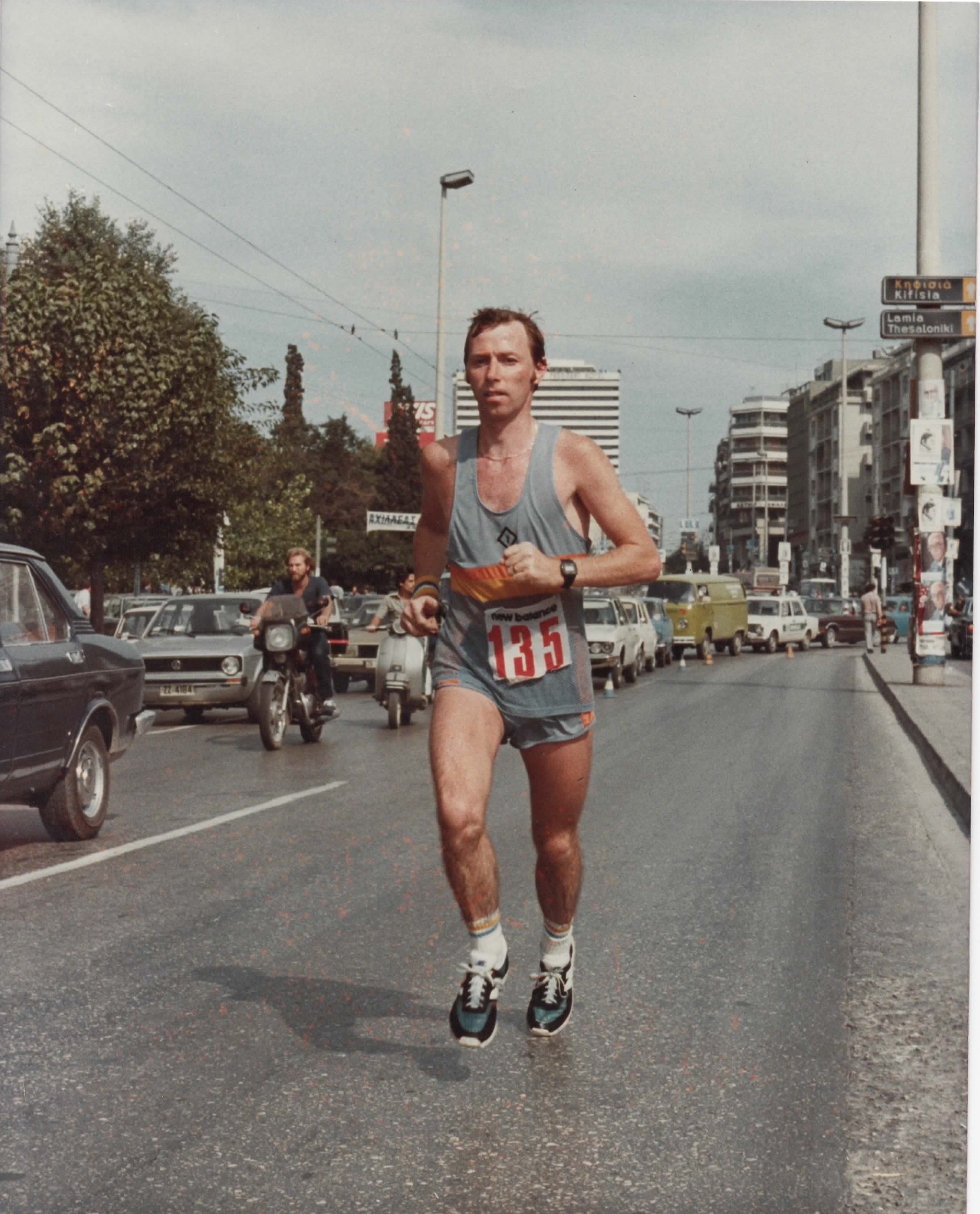

Simon Pride’s concentration from 2000 onwards on the marathon distance paid dividends. He recorded an excellent personal best of 2:16:27 in the 2001 London event and represented his adopted country, Scotland, in the Manchester Commonwealth Games marathon in 2002, finishing sixteenth.

After a brief return to ultra running when he finished third in the 2004 European 100K Championships in Faenza, Italy, Simon’s running reverted once more to shorter distances. Marathon victories include Belfast, Dublin, Lochaber and the Loch Ness event. He was Scottish Marathon Champion four times, in 2000, 2001, 2004 and 2006 (variously representing Keith, Metro Aberdeen and Forres Harriers). In addition he won umpteen 10Ks, 10 milers and half marathons as well as the M35 title in the Scottish Masters Cross Country Championships. Simon Pride was talented, versatile, brave and tough and his finest achievements (all as a Scotsman) were absolutely outstanding.

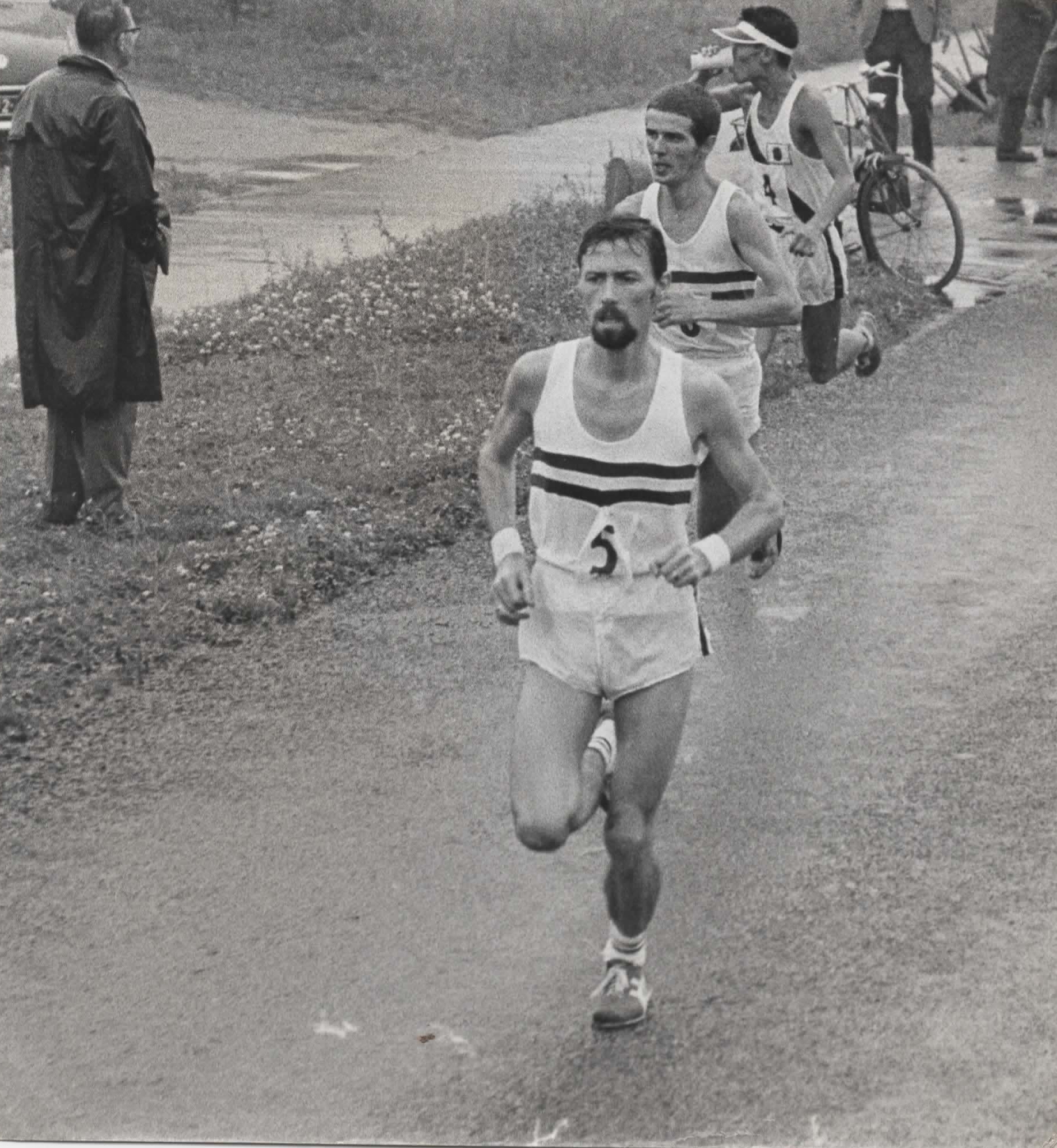

The 2001 Scottish Marathon Championships, for both Men and Women, started and finished in Elgin, as part of the Moray Marathons series on September 2nd. The Athletics Weekly report by Fraser Clyne was as follows.

“Simon Pride (Metro Aberdeen RC) retained the Scottish marathon title with a comfortable victory over a field of 162 runners, but women’s champion Trudi Thomson was in tears at the finish after missing the Commonwealth Games qualifying standards in tough conditions.

Pride, who clocked a Commonwealth qualifying time of 2.16.29 at London earlier this year, eased round the windswept course to finish in 2.28.34, well ahead of Martin Ferguson (City of Edinburgh – 2.32.50), who collected the silver medal for the second year in a row.

Ferguson had bravely tried to hold on to the former World 100km champion for much of the race but Pride proved to be much too strong over the last six miles. Robert Davidson (2.42.55) was third, while fourth placed Terry Coyle (2.43.48) was top M40.

The result virtually guarantees Pride a place in the Scottish team for next year’s Commonwealth Games in Manchester. He said, ‘I felt quite comfortable but there was a very strong headwind in the closing four miles which made things difficult. The time was unimportant. I just wanted to win and I’ve achieved that, so now I can relax. I’m happy.’

Pride also led Metro Aberdeen Running Club to the team title on a day when the North-East outfit also won the half marathon and 10k team trophies.

Trudi Thomson (Pitreavie AAC) came to the Moray race hoping to get the Games qualifying standard of 2.40, but the strong winds ruined any hopes she had of achieving that mark. She said, ‘I so wanted to get the standard. It was very hard in the first ten miles but, despite that, I was still on schedule at 20. Then it all fell away. I am so disappointed. I cannot believe how tough it was at the finish.’

Thomson, who was beaten by only six men, took little consolation from the fact that her 2.49.33 broke the course record of 2.51.09, set by Belgrave’s Frances Guy in 1987. Carol Cadger (Perth Strathtay) was second in 3.20.57 and Scarlett Courtney (Milne’s) took third spot in 3.21.54.”

Carol Cadger was a durable athlete who won the Scottish 50km title four times, in 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2002.

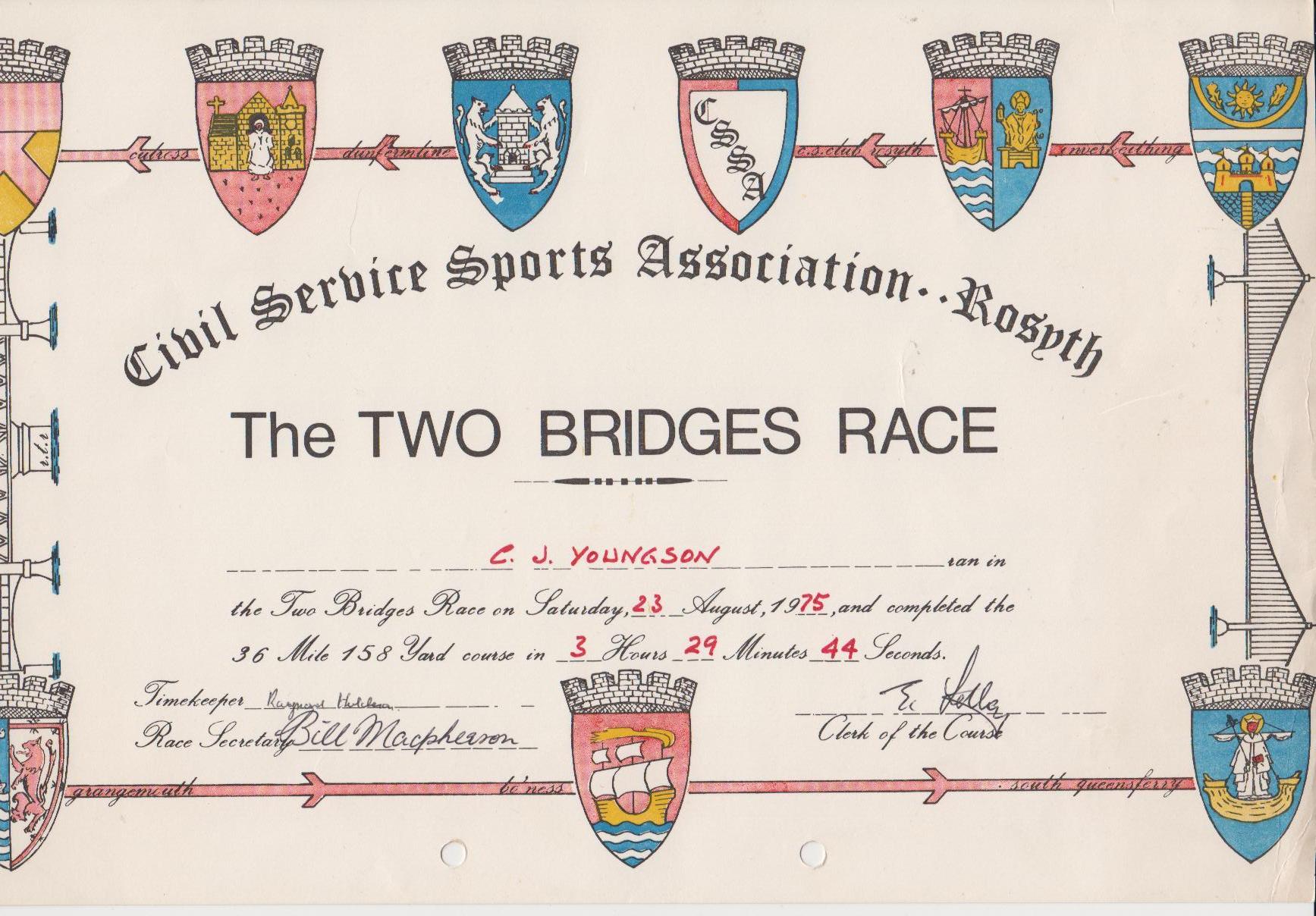

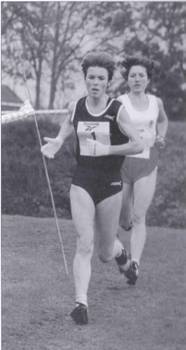

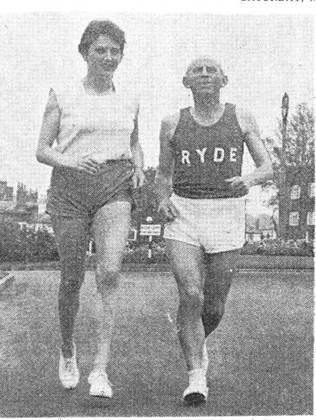

Despite the above reverse, near the end of a fine running career, Trudi Thomson had many highlights to look back upon. When she won her first Scottish Marathon title in 1992, she was only starting out. She raced a lot and was known for being a serious athlete who normally trained twice a day. At that time, a well-known former Scottish International steeplechaser and cross-country runner, John Linaker, advised her and was a frequent training companion. Trudi quickly became a good ultra-distance runner and in 1992 she also won the Two Bridges 36 mile classic in 4:48:51 and was to go on and win it in ’93 and ’94 as well. In 1993 she represented Great Britain in the World 100km Championships in Torhout and her team won silver medals.

In 1994 she won the Scottish veteran cross country and marathon titles, finished third in the UK Inter County 20 miles championship, and fifth in the Two Oceans 35 mile race in Cape Town. All this was merely training for an even more important race.

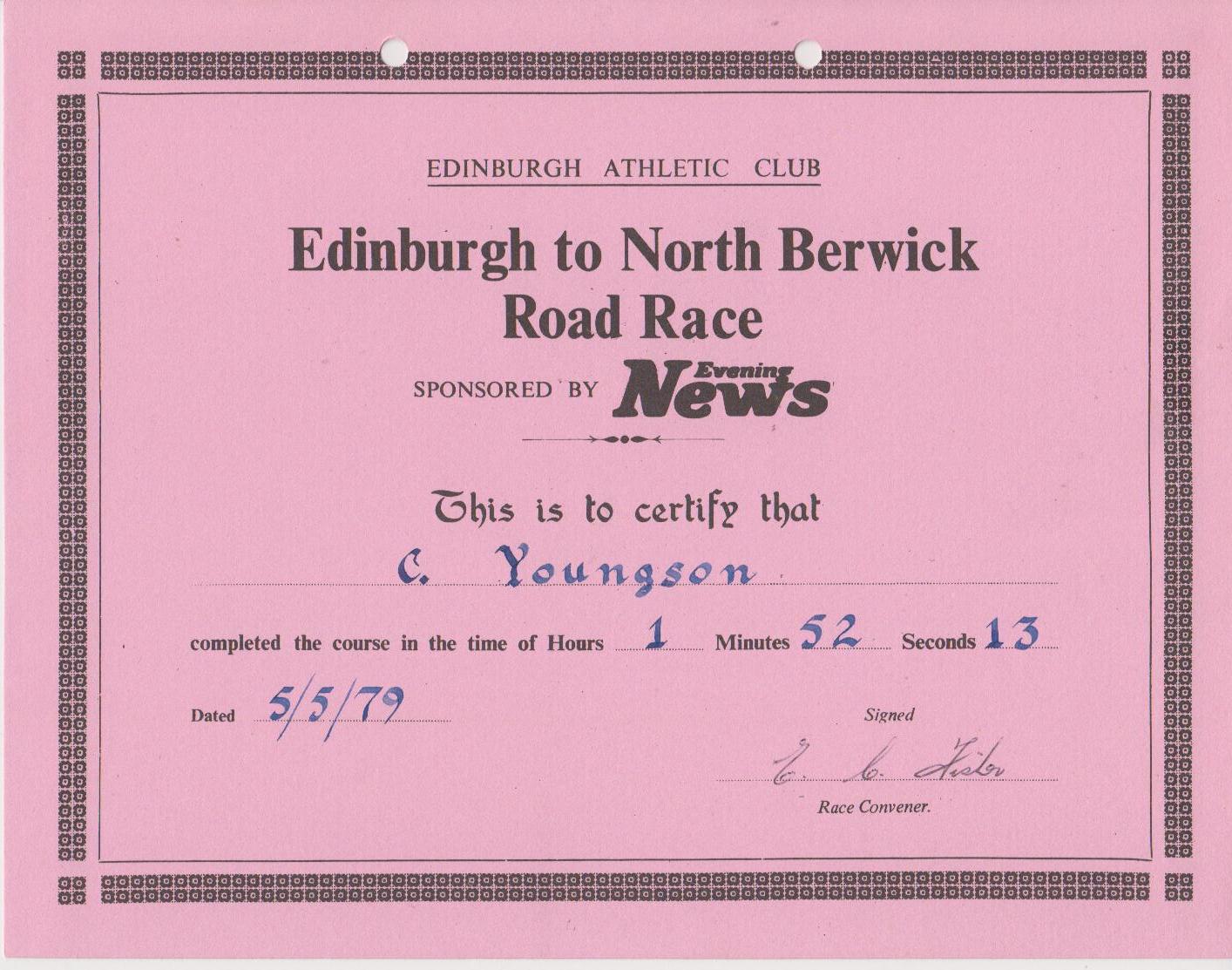

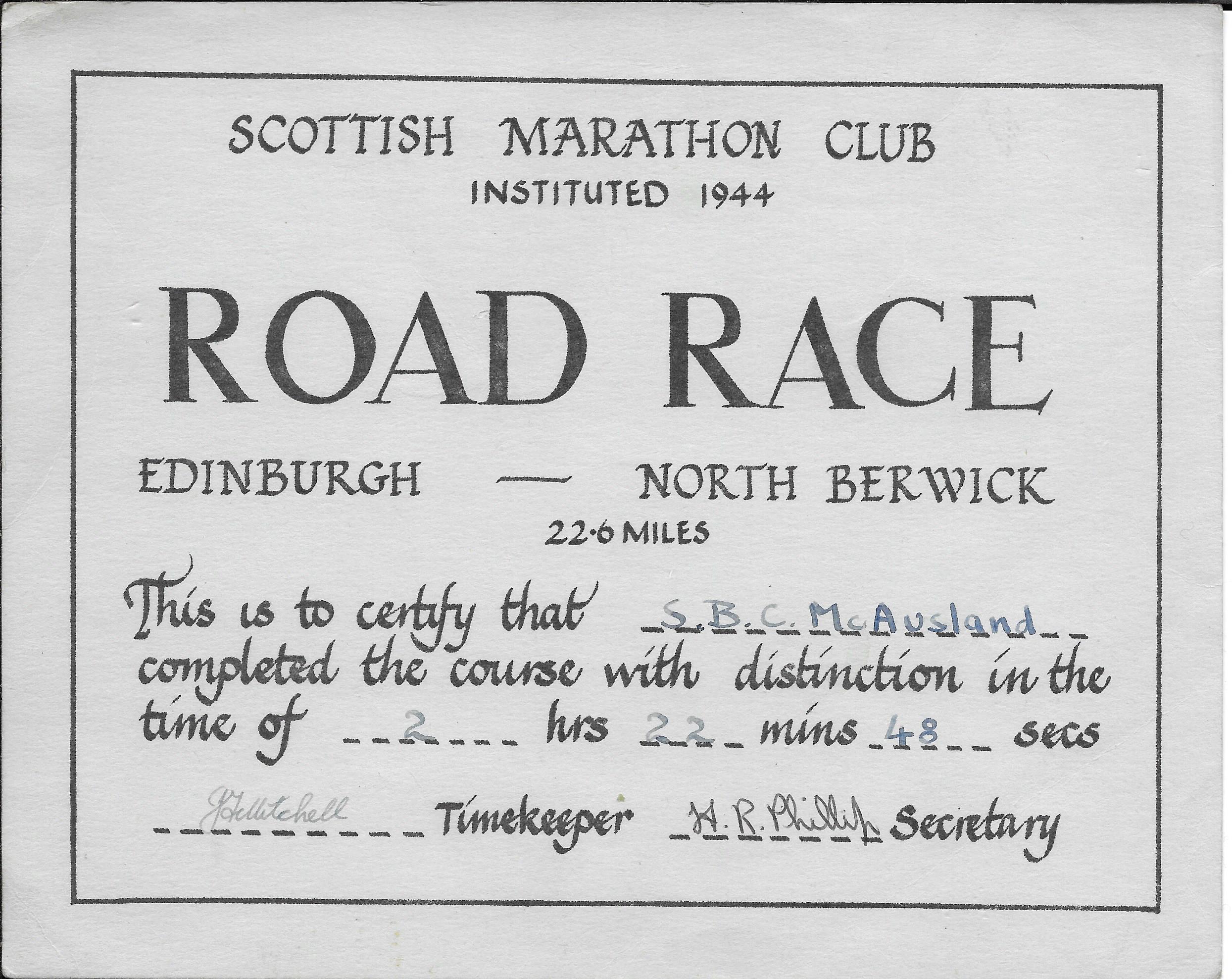

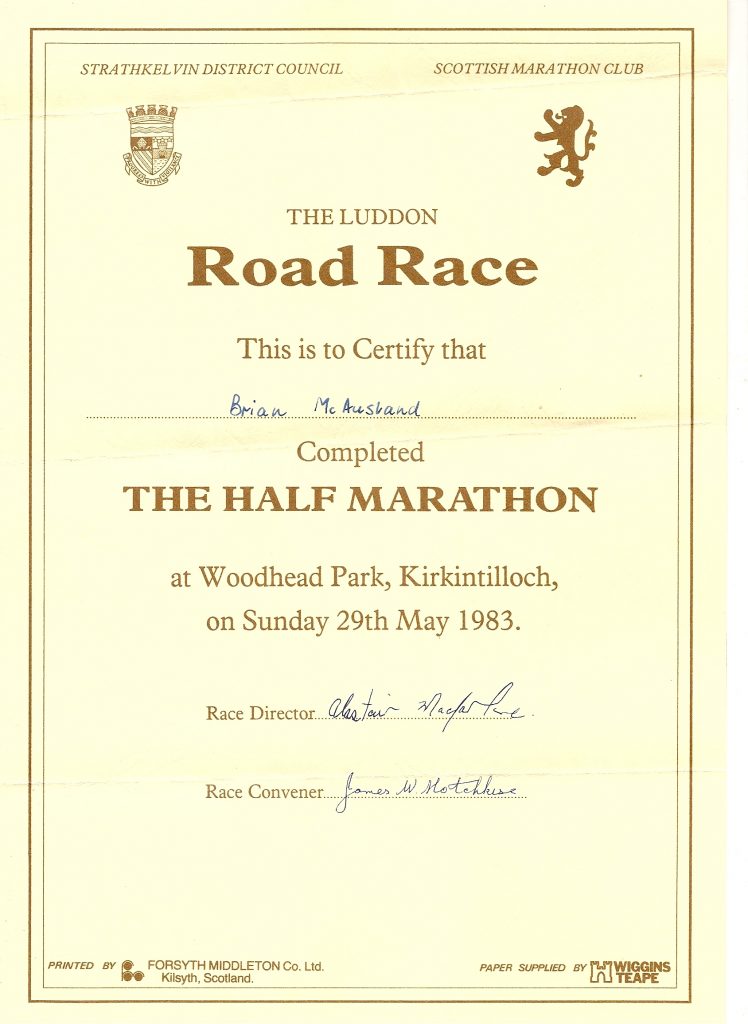

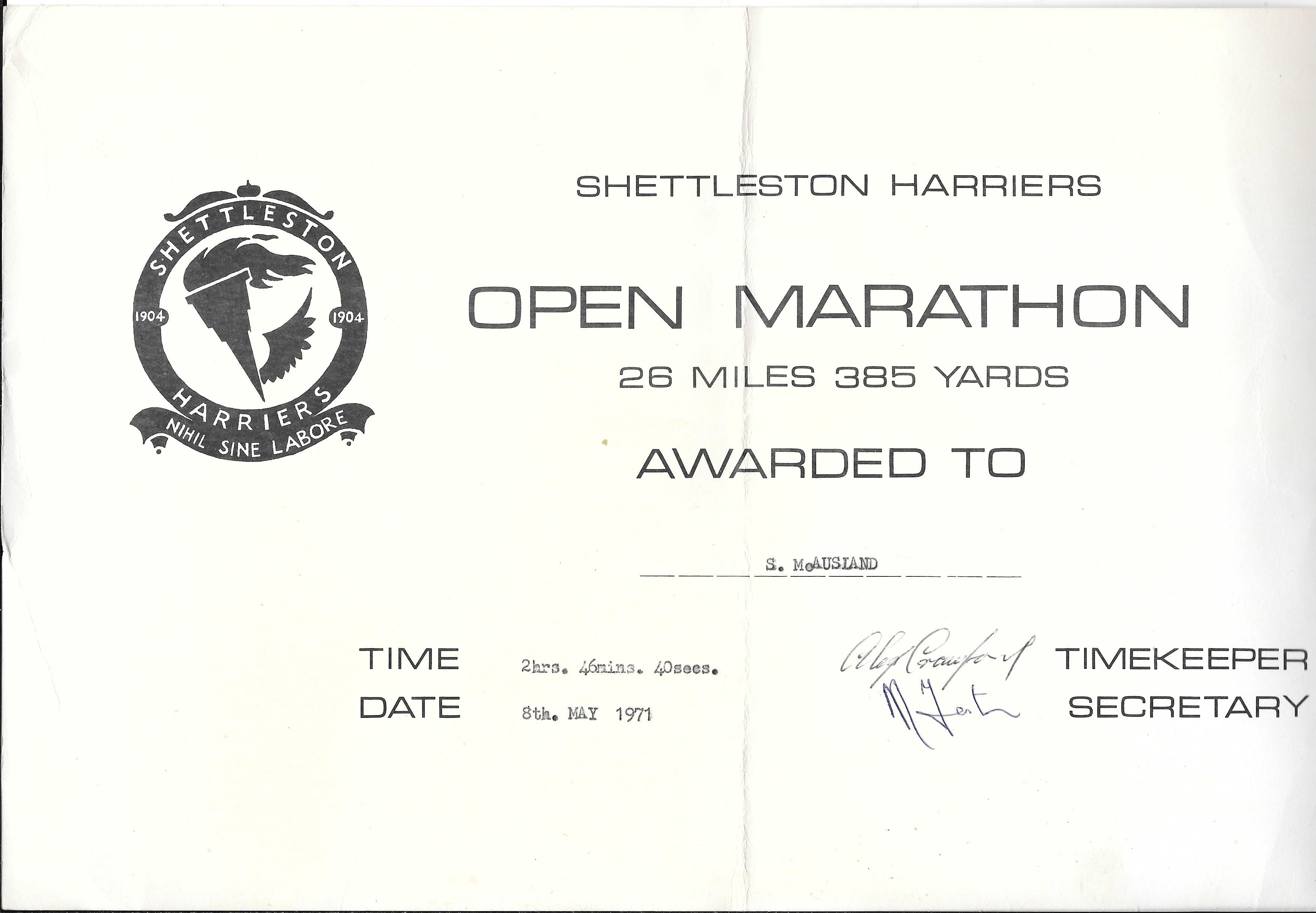

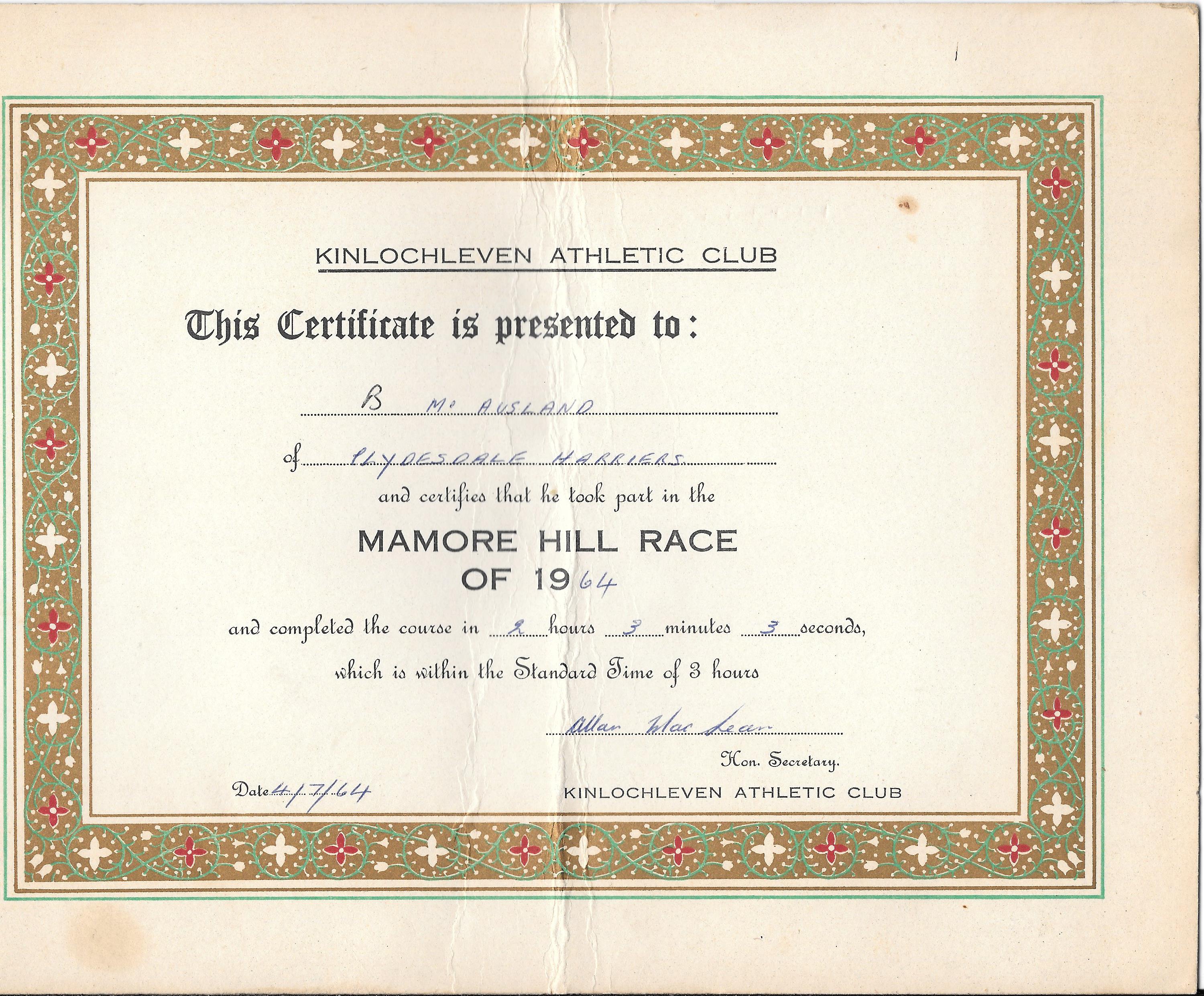

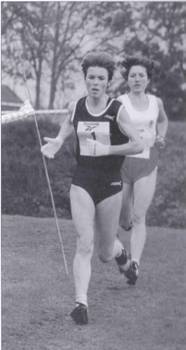

Trudi Thomson front-running a cross-country race

In the World 100km Championship at Lake Saroma in Japan, Trudi finished second individual in the 100K world championships in the wonderful time of 7:42:17 which was a Scottish and British record for the distance. She went on to win her third Two Bridges 36 Miles in a much faster time than before – 4:06:45 which is still the course record for this famous event which has sadly been discontinued.. The Edinburgh to North Berwick 22.6 miles road race was also won in a course record of 2:15:31. In addition she set a new personal best in the Dublin Marathon, recording 2.43.18. All this in the year when she celebrated her 35th birthday.

As a cross-country runner, Trudi Thomson won five titles (three W35 and two W40) as well as, in 1999, achieving W40 victory in the prestigious annual British and Irish Masters International Cross Country.

In 1995 she improved to: 10k in 34.59; Half Marathon in 74.48; and Marathon (Dublin again – in 2.38.23). Subsequently she ran for GB in the World Marathon Championships in Gothenburg, where she finished 22nd, three places behind Fatuma Roba who had won the Olympic Marathon in Atlanta.

Trudi Thomson’s successes continued for several years. For example, in 2000, the Valladolid Half Marathon was at the World Masters Championships where she won the W40 race in 78.16.

Trudi (far right) in the Royal Mail Letters team that won the 2003 Corporate Challenge in New York

In 2002, the Scottish Marathon Championship was held on 28th April, at the Lochaber Marathon in Fort William. Female gold medallist was Dawn Scott, twice silver medallist in the Scottish Hill Running Championship, from the local club Lochaber AC. Her time was 3.09.45. Second was Elaine Calder from Strathaven Striders (3.12.04) and third Debbie MacDonald from Hunter’s Bog Trotters (3.20.51.)

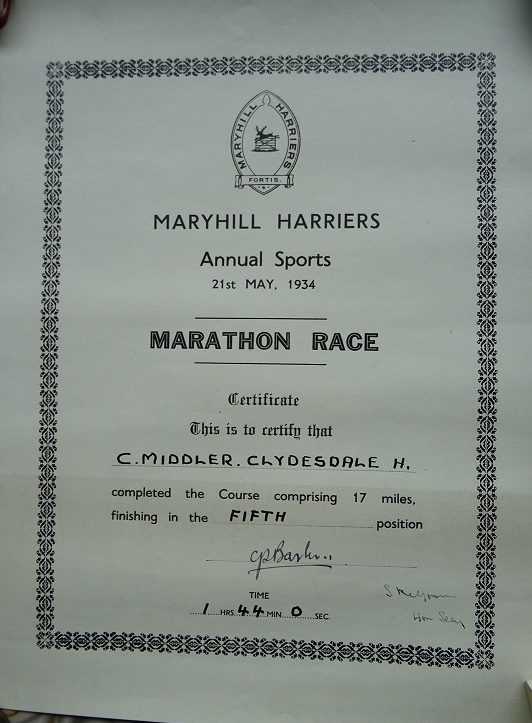

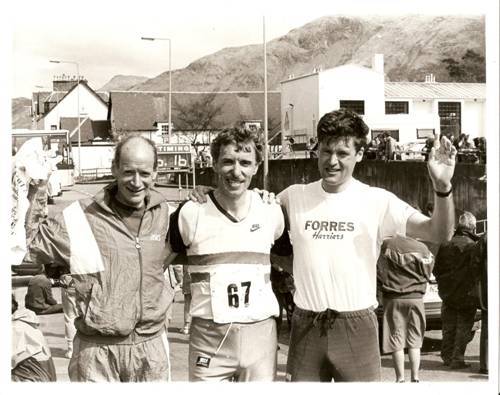

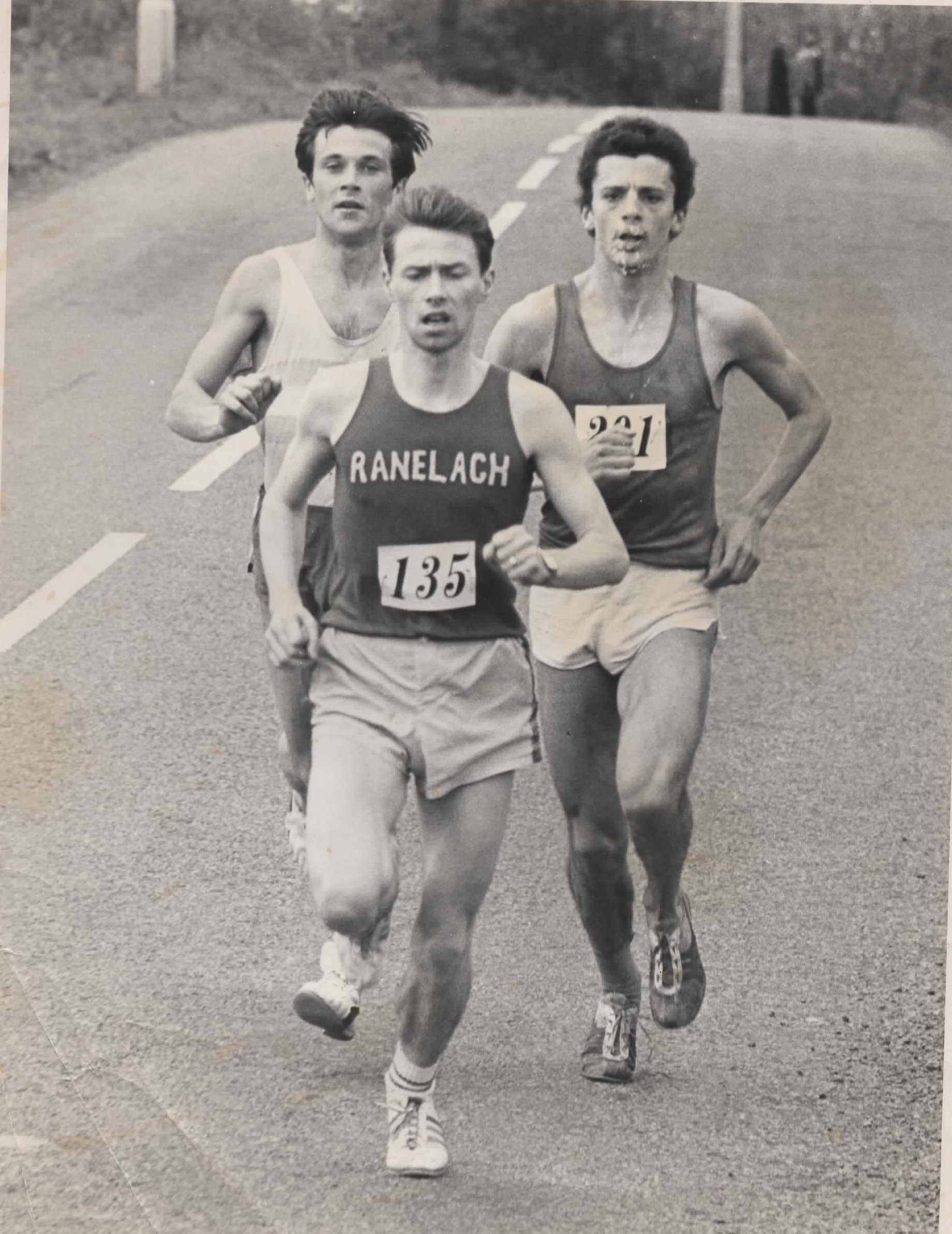

Jamie Reid (Law and District AC) secured his first Scottish Marathon title, recording the good time of 2.21.46. Some distance behind was silver medallist Brian Fieldsend (Inverness Harriers – 2.35.02) and third-placed Martin Ferguson (EAC – 2.36.20).

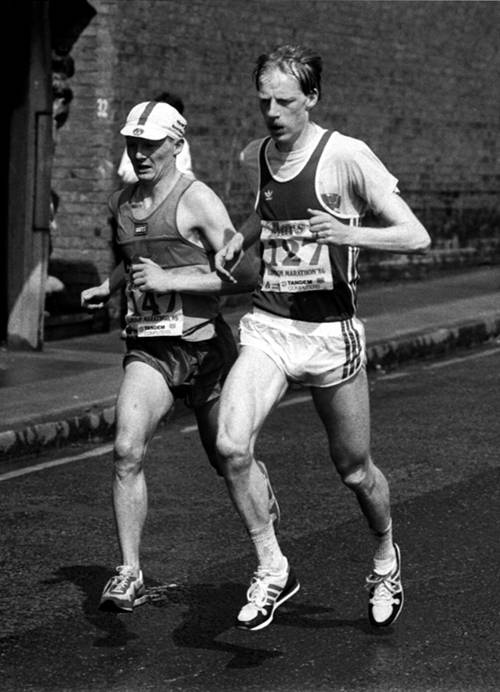

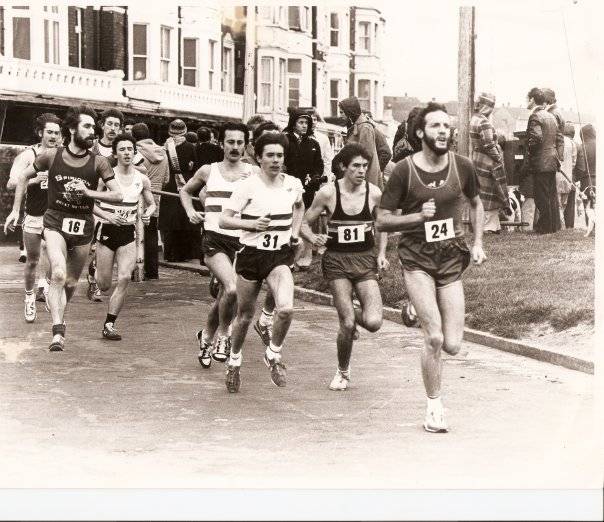

Jamie Reid

Back in 2000 after finishing a fine ninth in the Scottish Cross Country Championship, Jamie Reid’s 10k road best had been reduced to 30:49 and his marathon time (at London) to a lasting personal best of 2:21:16. Four weeks earlier he had taken the very last UK Inter Counties 20 Mile Championship at Spenborough in 1:47:59 running for the West of Scotland.

A very good year for Jamie Reid was 2002 when he ran 5000m in 14:35.43, 10,000m in 30:16.66, 10 miles in 49:46 and a half marathon in 67:07. In Lochaber, he ran right away from the rest of the field to win his first Scottish title in 2:21:46, just outside Simon Pride’s course record. During the summer he took his only Scottish track title winning the 10,000m gold at Grangemouth on a Wednesday evening in 31:14.31. He then switched clubs from Law and District AAC to Ronhill Cambuslang Harriers. This resulted in many team successes for Jamie Reid, including a Scottish Cross Country Relay win in 2003; Six-Stage Relay titles in 2005 and 2007; and 2008 National Senior Cross Country victory.

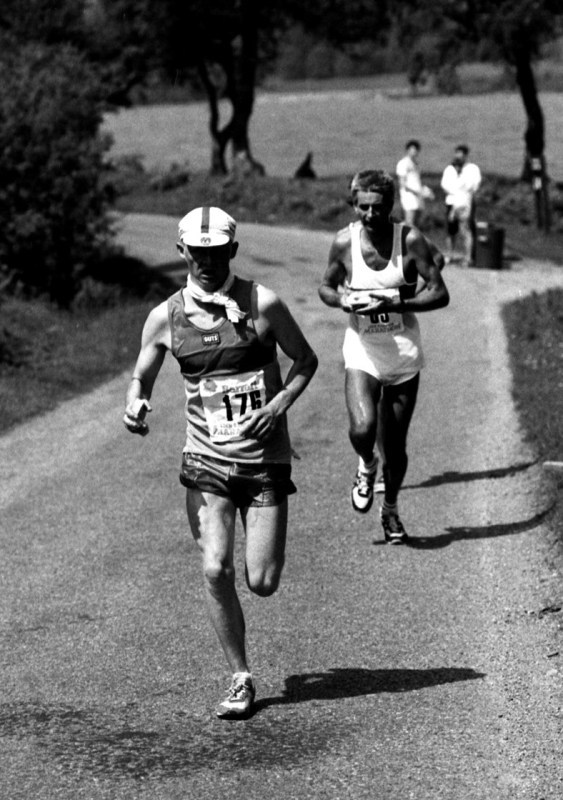

In 2003 Jamie Reid reduced his ten mile time to 48:51. Then on 31st August in the Elgin Moray Marathon in Elgin, over a much slower course, he retained his Scottish title in 2:34:08, still three minutes ahead of his closest rival James Snodgrass (Kilbarchan AAC – 2.37.20), with Andreas Merdes (Lothian RC 2.39.58) third.

Jamie in the Moray Marathon

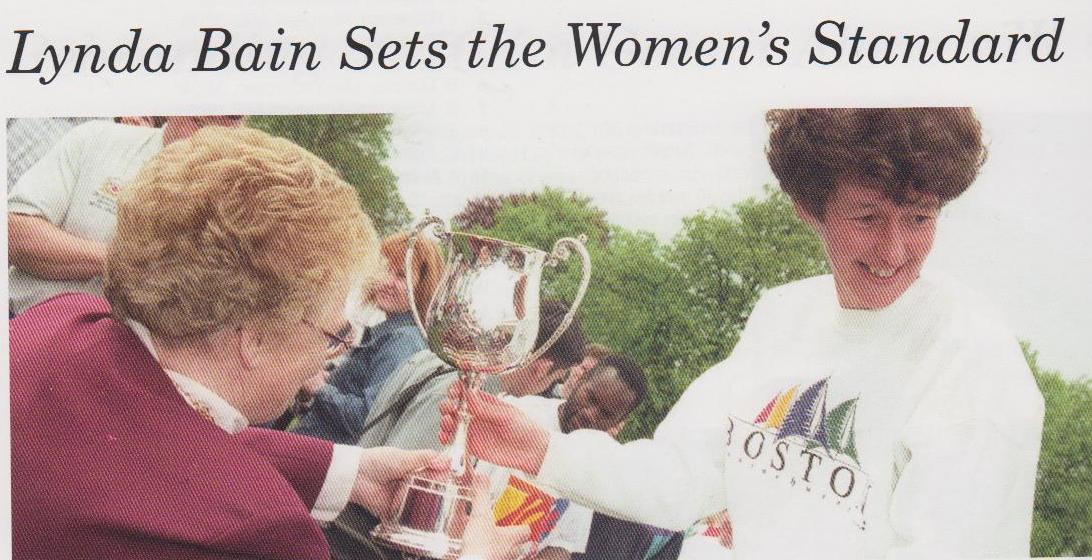

The 2003 Scottish Women’s Marathon victor at the Moray event was the indefatigable Kate Jenkins of Carnethy Hill Runners. Despite the marathon not being her best event, Kate won her third title at the classic distance, recording 3.09.18, with Morag Taggart (Dundee Road Runners) second in 3.10.14 and Margaret Anderson (Stonehaven AC) winning bronze in 3.18.04.

Kate Jenkins has had a long and very varied running career. In 2001, The Independent wrote an article about extreme hill-running, and especially the previous year’s West Highland Way race, including the following.

“More than 45 miles into the race, Kate Jenkins felt euphoric. On a hazy, sunny day she ran through birch-wood glades and over bubbling streams before careering into Glen Orchy in the Grampian Mountains. The formidable Ben Dorain towered over her path as she climbed steeply towards Loch Tulla, where the track headed north to Glen Coe.

Fifteen miles later, she was in desperate trouble. Her stomach was cramping, she felt faint and dizzy. Dehydration was setting in, she was losing her balance and she felt scared. In the middle of the desolate Rannoch Moor – a sombre expanse of peat bog covering 20 square miles – she started to panic. She had 35 miles still to run, and she didn’t know if she could manage five.

Kate, 27, who works for Scottish Forest Enterprise, was running the West Highland Way, from the suburbs of Glasgow to Fort William. For most fit people, it is a formidable 95-mile walk. For an élite few, it is an awe-inspiring hill run. In 18 years of races, fewer than 150 runners have finished; the West Highland Way is at the extreme end of a tough sport.”

“Kate Jenkins did eventually finish the 95 punishing miles of the West Highland Way in a record time of 17 hours 37 minutes. Holding off the dehydration, she fought through “a long silent spell of despair where I was convinced I had reached the limit”.

“It changed my life,” says Kate, who only began hill running seriously in 1996. “It makes you realise you are something you never knew you were. I wanted to spend more time with people who have experienced the same emotions. It is a high I will never experience again.””

Kate ran an incredible amount of races on all surfaces, for Gala Harriers, Carnethy Hill Runners and HBT. Between 1997 and 2012 she won the Moray Marathon twelve times! In addition she was Scottish Hill Running Champion in 1999 and 2001; and first Woman in the West Highland Way Race five times: 1999, 2000, 2003, 2004 and 2006. (She also won the 2004 Lairig Ghru Hill Race, which was 28 miles long, accompanied by Ben, the First Dog!)

Kate Jenkins en route to winning the 2006 West Highland Way Race

Simon Pride (Metro Aberdeen RC) was back to form in 2004, winning his third Scottish Marathon title with considerable ease. The event was held in Fort William once again, on 25th April, and Simon ran right away to secure gold in 2.21.21; with Andreas Merdes second in 2.37.50 and John Duffy (Shettleston H) third in 2.44.32.

Scottish Women’s Marathon Champion was Janet Laing (Portobello AC – 3.12.09), from Elaine Calder (Strathaven S – 3.3.18.44) and Maggie Creber (Carnethy HRC – 3.19.14).

In 2005, the event shifted to the Edinburgh Marathon. This had received significant sponsorship and was a genuinely Big City Marathon. The route had been changed to eliminate the tougher hills and was now a much faster course. Feedback from some of the competitors was generally positive: it was considered scenic and well-organised if a little expensive. There were 4421 finishers.

Africans filled seven of the first eight places. Zachary Kihara was first man in 2.15.26; and Russian Zinaida Semenova first woman in 2.33.36.

However Scottish Women’s Marathon Champion (fourth overall) was Shona Crombie-Hicks (Bourton) in the good time of 2.44.58; silver medallist Ros Alexander (Carnegie H – 2.48.25) was fifth overall); and bronze went to Elka Schmidt (Bellahouston RR – 2.54.16), seventh overall.

Scottish Men’s Marathon Champion (ninth overall) was Robert Gilroy (Ronhill Cambuslang H – 2.26.42); in front of his club-mate Jamie Reid (2.30.51); and third was durable former Scottish International Marathon runner Frank Harper (Carnegie H – 2.35.54).

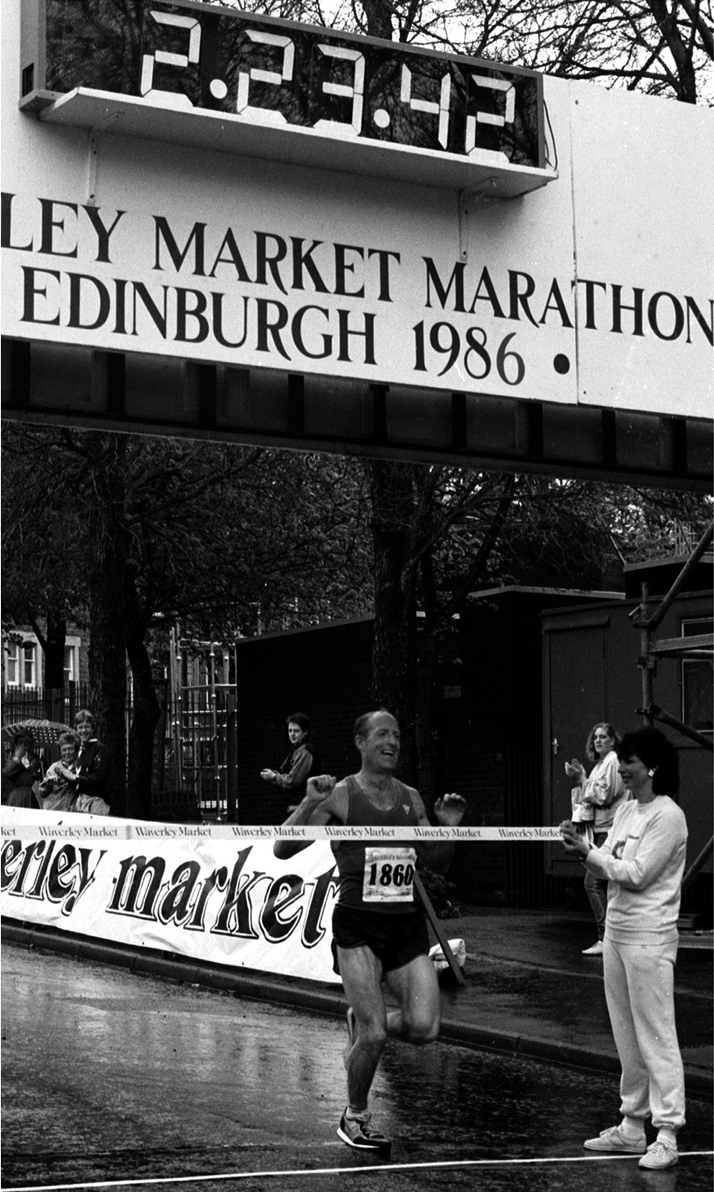

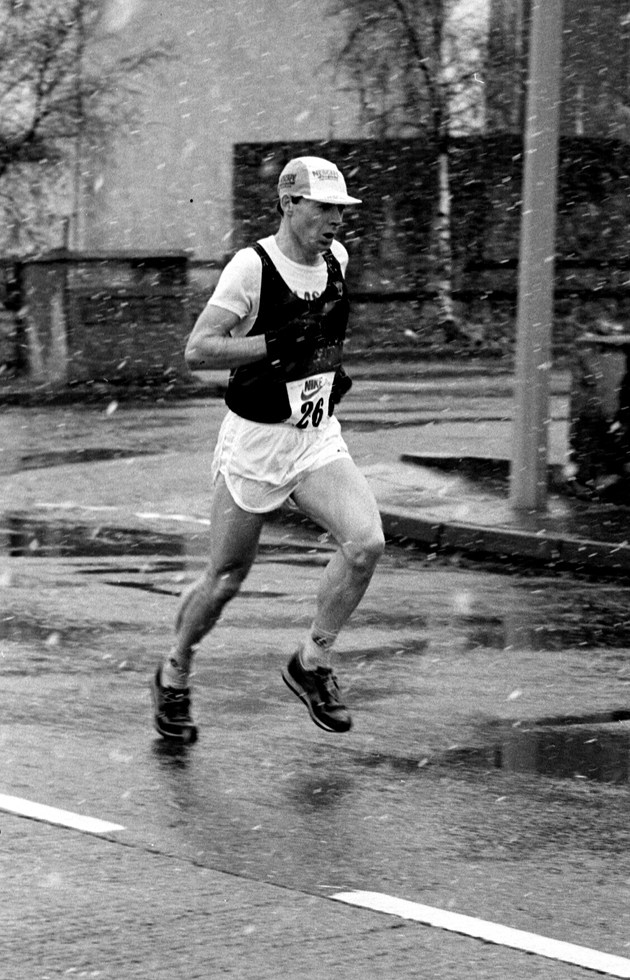

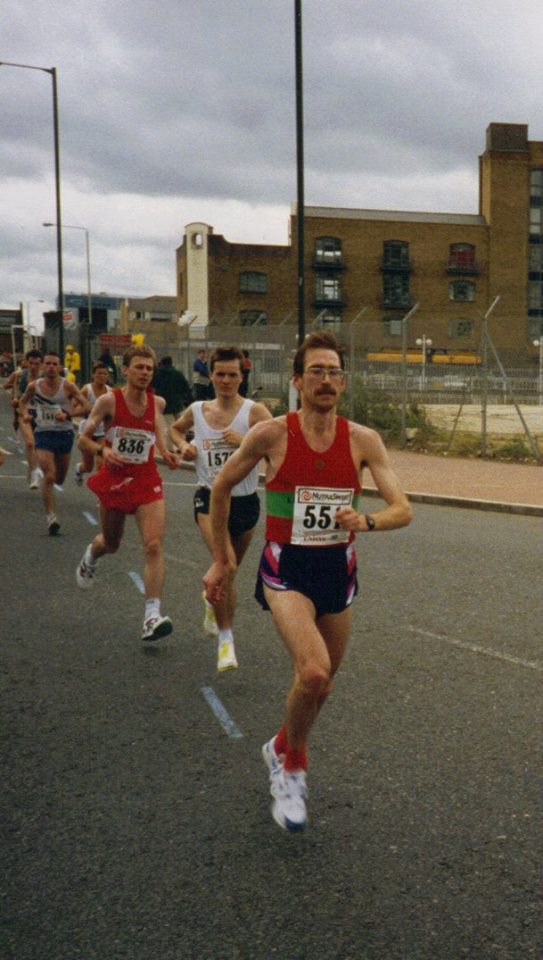

Frank Harper, aged 47, was first M40 in this Edinburgh Marathon. In 1986 he was fourth (first Scot) and set a new best of 2.18.44 while running for his country in the Glasgow Marathon.Then in 1988, Hammy Cox and he were first and second in the Aberdeen Marathon. When Doug Cowie (Forres Harriers) finished fifth, this ensured that Scotland defeated England (as well as Wales) for the only time in the Aberdeen Home International Marathon series.

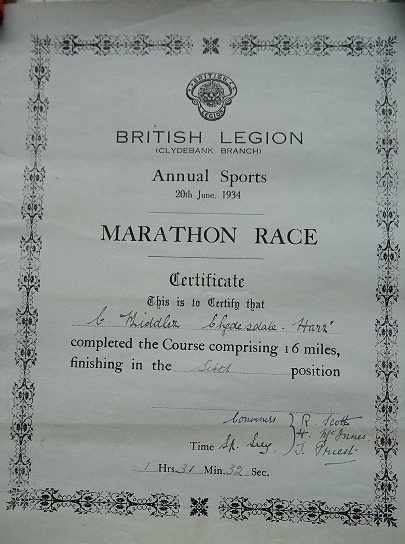

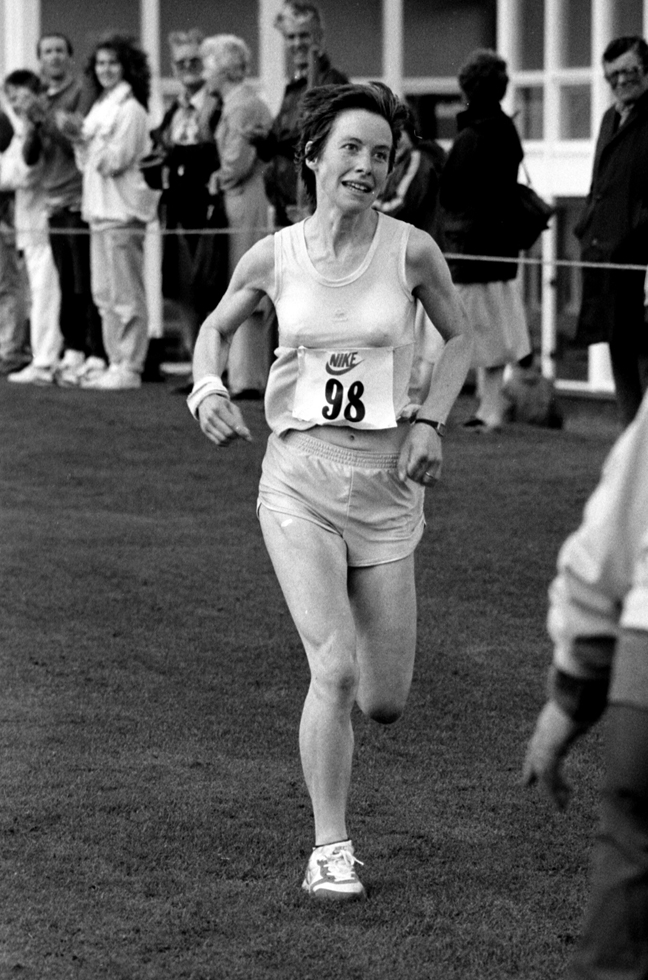

Shona Crombie-Hicks

Shona Crombie-Hicks was a former jockey who took up running to control her weight. She came originally from Aberdeen but moved to Portsmouth when young. Having become a marathon runner, she won her first three races: in Lanzarote, Manchester and Copenhagen. She was selected for the Scottish Marathon team in the 2002 Manchester Commonwealth Games but had to withdraw due to injury. Undaunted, once recovered she entered the 2003 Flora 1000-mile challenge, walking one mile every hour for 1000 hours, and finishing by running the London Marathon. The event started on March 2nd 2003. At 8.45 a.m. on April 13th, the five remaining competitors completed the 1000 miles together. Then they ran the London Marathon – and Shona Crombie-Hicks was by far the fastest, recording 3 hours 8 minutes! Later on, Shona set records for marathons in Lanzarote, Jersey and Guernsey. Her personal best time was an excellent 2.38.42 in the 2005 Berlin Marathon; and she also competed for Scotland in the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games.

As late as 2015, Robert Gilroy has continued to improve, due to hard training, involving well over 100 miles per week. He lifted the Scottish 10 miles road title in 2014; and has had many M35 victories including the British Masters Cross Country Championship; as well as many successes with formidable Cambuslang Harriers teams, for example winning the Scottish Masters Cross Country .

Robert Gilroy

2006

At the Loch Ness Marathon, near Inverness, Scottish Women’s Marathon Champion was Jennifer MacLean (City of Edinburgh – 2.58.57); second Iona Robertson (Bellahouston RR – 3.14.02); and third Erica Christie (Bellahouston H – 3.14.10).

Jennifer MacLean also won the 2007 Scottish Half Marathon Championship; and the Scottish Masters Half Marathon title in 2013. In 2009 and 2010 she was victorious in the W35 Scottish Masters Cross Country Championships.

Simon Pride (Forres Harriers) won his fourth and final Scottish Marathon title in 2.22.25; in front of the consistent Jamie Reid (Cambuslang – 2.24.04); and Stephen Wylie (Cambuslang – 2.30.09).

Stephen Wylie enjoyed considerable success during his running career. For example he won the Scottish 10 miles road title in 1993; was first in the Scottish Half Marathon Championship in 2003 and 2004; and lifted the Scottish M35 Masters Cross Country crown in 2009. Of course he had shared in many team wins with redoubtable Cambuslang teams.

2007

In Elgin, at the Moray Marathon, the Scottish Women’s Marathon title was won, for fourth and final time, by Kate Jenkins (Carnethy HRC – 3.10.43); in front of K. McKinnon (Carnegie H – 3.16.27); and L Schumacher (3.18.09).

Jamie Reid (Cambuslang – 2.33.11) won his third Scottish Marathon title, gaining revenge on Simon Pride (Forres H – 2.33.46). Bronze medallist was David Gardiner (Kirkintilloch – 2.38.07).

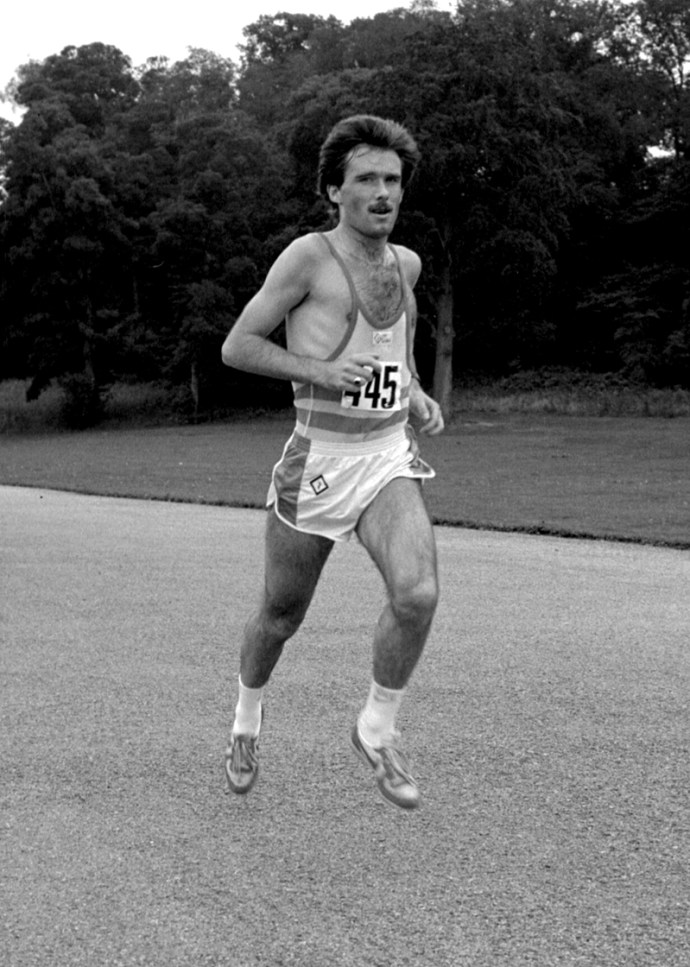

Jamie Reid wrote very frankly about this race: “My most recent Scottish title was at Elgin in 2007 where I had my first marathon victory over Simon Pride. The previous day, my girlfriend Roisin and I had driven north as she was competing in a a six-a-side shinty tournament near Inverness for her club, Tir Connail Harps from Glasgow. I spent the afternoon watching the tournament, drinking diluting juice and eating large amounts of cake! Afterwards we drove to a B&B in Elgin where we checked in and went out for a meal. We settled for some pizza and relaxed talking about the shinty that afternoon and the race the next day. I wasn’t really nervous as I wasn’t expecting much as recent races hadn’t gone particularly well. I had hit the over-training button again as I had logged a tremendous mileage (maximum of 144 miles per week), switching to this after my best ever fifth place at the National Cross-Country Championships in February. It hadn’t improved me, only made me worse. Never mind, I entered the marathon, hoped for a solid run and then I could look forward to the autumn relays – my favourite part of the season. The morning of the race we had coffee in the hall after picking my number up. I saw that Simon Pride was entered, along with Adam Reid from Peterhead and David Gardner from Kirkintilloch whom I knew fairly well.

Early pace was slow as the four of us settled down and let the countryside pass by. The day was warming up and there was little wind. I managed to get some drinks from Roisin as the race progressed, with the pace beginning to pick up as we passed Burghead (c14 miles). Simon and David pulled away and I knew it was too fast for me. In the distance I could see Simon moving ahead of David, but as we neared Lossiemouth, I could see I was gaining some ground. The sun by now was shining fiercely and I could sense a silver medal. I managed to pass David in Lossiemouth offering words of encouragement to each other, and I now looked to see how far ahead Simon was. He was out of sight.

Still, always believe – funny things can happen in the marathon. I finally caught sight of him as we entered the woods around 20 miles and I checked his lead in seconds. I can’t remember exactly but it must have been at least a minute. After a mile or so, I checked again – it was now around six or seven seconds less. A quick calculation in my head told me it would be close if we maintained the same pace, so I pushed on. Three miles to go, I could see Simon more clearly now and I calculated I could catch him by the end if we both maintained the same pace. Roisin was at this point in the car and she drove quickly back to the finish.

Every step was taking me closer to Simon now and the Scottish title was back in my head. What will happen when I catch him? How much has he left? Is he tiring or just unaware that I’m coming through? I caught Simon just as we entered the outskirts of Elgin, around a mile to go, and I decided to give it a push on to try to discourage any attempt to try to stay with me. Thankfully for me it worked and I went on to win in 2:33:11 with Simon not far behind and David taking bronze – marathon title Number Three! A slow time for all three of us, and perhaps highlighting the dropping standard, but it was one of the few marathon races I’ve run which had been tactical and a real ‘race’. I knew that, due to injuries, Simon had been past his best (although he had won the Scottish Masters M35 title in 2006), and neither David nor I had been at our peak, but it remained a very happy day for me. The rest was spent celebrating with ice-creams in Lossiemouth before driving south to Aviemore where we spent the night and I stuffed myself with burger and chips, washed down with chocolate fudge cake and ice cream!”

2008

At the Lochaber Marathon, near Fort William, the Scottish Women’s Marathon Champion was Rebecca Johnson (3.05.18); in front of Louise Beveridge (Metro Aberdeen RC – 3.13.38); and Kate Jenkins (Gala Harriers – 3.15.35).

The Scottish Men’s Marathon title was won by Stuart Kerr (Kirkintilloch – 2.34.01); in front of Keith Buchan (Fraserburgh AAC – 2.43.12); and Paul Hart (Dumfries RC – 2.45.10).

2009

In the Edinburgh Marathon, Scottish Women’s Marathon Champion was Toni McIntosh (Ayr Seaforth AAC – 2.47.18); in front of Jennifer MacLean (EAC – 2.51.37); and Izzy Menzies (3.02.45).

Earlier in 2009, Toni McIntosh had won a silver medal in the Scottish National Cross Country Championship, behind multiple winner Freya Murray (who went on to run for GB in the 2012 London Olympic Marathon). While at Stirling University, Toni was Scottish Half Marathon victor in 2003 and 2004. In 2009 she won not only the Scottish Marathon but also the 10k and Half Marathon titles! In addition Toni was first Briton in the 2009 Great Scottish Run.

Toni McIntosh (right) on the podium after the 2009 Scottish Cross Country Championship.

The Scottish Men’s Marathon title went to Martin Williams (Ronhill Cambuslang Harriers) in the good time of 2.18.24. Second was his team-mate Chris Wilson (2.26.36); and third Robert Turner (Harmeny AC – 2.33.50)

Martin Williams was based in the Midlands and ran for Tipton Harriers and the Police. In 2011 he won a silver medal in the Scottish Half Marathon Championship. However his peak was in 2010. After a fine 2.17.36 in the Seville Marathon he ran representative marathons for Scotland in the Delhi Commonwealth Games and for GB in the Barcelona European Championships.

In 2010, the Scottish Marathon Championship, for the first time, was held outside Scotland – as part of the London Marathon, which is held on an extremely fast course. One effect of this innovation was that the winning times were much faster than usual. Two of our very best athletes: Susan Partridge and Andrew Lemoncello were worthy gold medallists.

Susan Partridge (VP City of Glasgow) won in 2.35.57, the fastest time set by a Scot in the history of the Scottish Marathon. Second was Shona McIntosh (HBT – 2.48.46) and third Nathalie Christie (EAC – 2.55.52). Shona won four Scottish Cross Country Championship team medals with the Bog Trotters, including gold in 2011. In London 2015 she improved her marathon best to an impressive 2.40.14.

Andrew Lemoncello (Fife AC) finished in 2.13.40, which was also the fastest time set by a Scot in the history of the Scottish Marathon; while Englishman Neil Renault (Edinburgh AC) recorded 2.18.29 for the silver medal; and Ross Houston (Central AC) ran 2.22.49 for bronze. Neil Renault’s fastest Half Marathon was an impressive 64.47; and he also won a silver medal in the 2012 Scottish Half Marathon.

For Susan Partridge this was merely one significant mark in a long, successful running career. In 2011 she represented Great Britain in the World Championship marathon in Daegu, Korea. Her international progress before that was impressive. She competed in: the World and also the European cross-country championships (helping Britain to team gold in the latter); the 2006 Commonwealth marathon; the 2010 European Marathon; and she had top-thirty places from the World Road Running and World Half-Marathon Championships.

She made an early impact on the Scottish cross-country scene, winning the National under-17 title in both 1996 and 1997. In 2003, Susan won the Scottish Athletics Federation Cross-Country title and then became Scottish Champion at 5000m.

In the 2005 London Marathon, Susan Partridge progressed to 2.37.50. In October, she ran for GB in the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships in Edmonton, Canada, finishing 25th in 73.49, only a few seconds slower than her personal best of 73.10, which was set when she won the Bath Half Marathon in March.

2006 was Commonwealth Games year and Susan’s preparations included a PB 10k (33.19) and a good half-marathon (73.14) in Spain, before finishing a solid tenth (2.39.54) in Melbourne, Australia on the 19th of March.

After some slightly less impressive performances, the 2010 London Marathon showed a return to form. As second British woman home, she was selected as part of the GB team for the European Championships at the end of July. After a couple of weeks rest, she got back into 90 to 100 miles per week training. In the heat and humidity of Barcelona she finished in 2.39.07 and Michelle Ross-Cope (14th), Susan (16th) and Holly Rush (20th) were the three scorers for the six-women GB team which won European Cup bronze medals.

The 2011 London Marathon produced a new PB (2.34.13), 25th place (3rd British woman) and selection for the World Marathon Championships in Korea at the end of August. There, in stifling conditions, she ran a calm, sensible race and came through strongly to finish a meritorious 24th (1st GB, 6th European), in 3.25.57) from the 54 starters.

London 2013 produced another outstanding run. The Scotsman reported: “When eventual winner Priscah Jeptoo pulled away, the Scot maintained a steady pace to cross the line 9th in 2.30.46, a time three minutes quicker than her previous best and good enough for fifth in the Scottish all-time rankings, earning a trip to Moscow in August for the World Championships marathon. After being the top British woman and inside the qualifying standard, the only question was whether Partridge (who also secured the 2014 Commonwealth Games standard) wanted to go to Moscow, and she certainly did.”

Susan Partridge moving strongly in the Moscow World Marathon

The afternoon of the tenth of August 2013 was a very humid afternoon in the Russian capital, when 72 athletes started the Women’s World Championship Marathon. Susan, who by now had a full-time job as a researcher in joint replacement at the University of Leeds, set off very carefully, well down the field. After reaching the finish in the Luzhniki Stadium, Olympic Park, she said, “It was all about places today. I was way back at the start and for a minute wondered if I’d been a little bit cautious, but once I got my rhythm going I started to come back and pick people off.” Live television coverage made clear how well Susan was moving up throughout the entire race. Eventually she crossed the line in 2.36.24 to secure a fine tenth place (third European). In the history of the event, Great Britain previously had only four top-ten finishers: Paula Radcliffe (1st in 2005); Joyce Smith (9th in 1983); Mara Yamauchi (9th in 2007); and Sally Ellis (10th in 1991).

Freya Ross, Susan Partridge and Steph Twell after the 2014 Great Scottish Run Half Marathon.

Then, in 2014, Susan represented Scotland in the Glasgow Commonwealth Games Marathon. Boldly, she kept up with the fast early pace but eventually, as first Briton, had to settle for sixth place in 2.32.18.

Susan said that she had no regrets and had given herself a real chance – a medal would have been great but “It was an unbelievable experience” in front of the cheering home crowd.

Susan Partridge in Glasgow

Andrew Lemoncello was an extremely successful Scottish male distance athlete, although his career was hampered by injury. Andrew grew up in St Andrews and attended Madras College. He joined Fife AC and was coached for several years by Ron Morrison.

Andrew showed immense promise, even before he was thirteen. Then he went on to win the Scottish Junior National CC in both 2002 (when Fife was first team as well) and 2003. In addition he had started running the steeplechase, winning the Scottish 2000m title in the appropriate year – 2000.

Andrew was offered a scholarship to Florida State University in Tallahassee, which let him train and race regularly with top athletes. 2005 was a busy and successful year. After a hectic Spring season in America, producing a number of track bests, in July Andrew triumphed at the AAA Championships, winning the steeplechase in 8.33.93. Subsequently he was selected for the Great Britain team for the Helsinki World Championships. As part of his build-up he won the Scottish 5000m title; but unfortunately did not get past the heats in Finland.

2007 was World Championship year once more and Andrew Lemoncello responded well. He won the Scottish East District CC championship, followed by a demanding series of races in America. A highlight was second place (behind Kenya’s Barnabas Kirui) in the NCAA steeplechase championships in June. Shortly after that, he was third in the European Cup. Then in Metz, France, Andrew ran a new steeplechase best of 8.23.74; and then won the GB World Trials and AAA Championship. Sadly, although he had no trouble retaining his Scottish 5000m title once more, Andrew fell ill, suffered side effects from an unfamiliar energy gel, and really struggled in his World Championship heat in Osaka. When he was interviewed (for The Winning Zone) a couple of months later, Andrew vowed to learn from the experience and also stated that he believed that he could indeed continue to be world class and that his longer term ambition was to become a successful marathon runner.

2008 was Olympic year. In March, having been fourth in the Inter-Counties CC selection race, Andrew Lemoncello ran for Britain in the World CC Championships in Edinburgh. He finished third in the European Cup steeplechase once again, and shortly afterwards came third in the AAA Olympic Trials. At the last moment he qualified for the GB team by running an outstanding new best of 8.22.95 on the 18th of July in the Paris Golden League. However he did not qualify from his heat in Beijing, despite running a decent time of 8.36.06. In retrospect, he believed he peaked too early. Then he came back to Scotland and, for the fourth year in succession, won the Scottish 5000m title, this time defeating the two Shettleston Eritreans.

Having retired from steeplechasing, Andrew Lemoncello pursued his marathon aspirations by concentrating mainly on the road, although in April 2009 he did run a very good PB for 10,000m (27.57.23) in California. Having run a Texan downhill half-marathon in 61.52, Andrew represented GB yet again, this time in the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships in Birmingham, where he finished a respectable 26th (First Briton) in 63.03. Then in December he was 29th in the European CC Championships in Dublin.

After a hard winter grinding out the miles, Andrew Lemoncello was ready to make his debut in the 2010 London Marathon, and although he had hoped to go a little faster, was quite happy about his eighth place (first Briton) and time of 2.13.40. When he continued to show fitness by being first man in for the UK at the Great North Run Half Marathon in September 2010, and had a number of good runs in 2011, all seemed well for London 2012. Sadly, Andrew Lemoncello tore a hamstring before he had a very bad time in the Fukuoka Marathon in December 2011 and did not have time to prepare for the Olympic Selection race at London (in April 2012). He did finish fifteenth (and second Brit in 2.15.24) but the time was too slow for the team.

Unfortunately, by the time the 2014 Glasgow Commonwealth Games came round, Andrew Lemoncello had not shaken off his injury problems. Nevertheless he acquitted himself well in the 10,000m, finishing twelfth and first Briton.

Andrew Lemoncello in Glasgow

(The following section, from 2011 to 2015, is based almost entirely on reports by that former World-Class marathon runner and current eminent sports journalist, Fraser Clyne.)

2011

Great Britain international Tomas Abyu (Salford Harriers) defeated a field of more than 3,000 runners to win the 10th anniversary Baxter’s Loch Ness marathon yesterday while runner-up Ross Houston (Central AC) turned in a fine performance to collect the Scottish national title.

Ross Houston in 2012

Abyu, who also won in 2003 and 2010, recorded 2hr 20min 50secs to finish 15secs ahead of Houston who was rewarded with a personal best time.

Although there was little between the top two at the end of the 26.2 mile race, Abyu felt he was always in control.He said:“I had a very good run in the second half of the race. Ross Houston was pushing the pace, but I felt very comfortable.”

Houston, who won the Scottish 10Km title a fortnight ago, was also happy with the outcome. He said:”We were running together until the 16 mile mark when Tomas made a break. I couldn’t stay with him, but after a while the gap he had opened never increased. I finished quite strongly, which was pleasing and I’m delighted to win the Scottish title. I had hoped to get under 2:20 but that will have to wait for another day.”

Chris Wilson (Ronhill Cambuslang) clocked 2:25:15 to take third position for the second time in three years. His club-mate Kerry-Liam Wilson won bronze in 2.31.06.

Veteran Lisa Finlay (Dumfries Running Club) set a personal best time of 2:59:14 to win the Scottish Women’s Marathon title, as well as the Scottish Masters gold medal. [She went on to win the Scottish 10 miles title in 2014; as well as Scottish Masters titles in 2014 (10 miles); 2013 (Marathon) and 2015 (Half Marathon).]

Shettleston’s Carole Setchell (3.02.56) slashed her best time by 15 mins to take the silver medal while ultra distance specialist Gail Murdoch (Carnegie Harriers) took bronze in 3:09:37.

Finlay said:”There were a lot of good runners taking part, making for stiff competition. I ran my own race, sticking to my plan and was delighted to win, and even knocked a few seconds of my previous best. It’s a lovely course and the spectators along the route were really warm and supportive.”

Bellahouston’s Erica Christie maintained her remarkable record of consistency when finishing eighth. The Glasgow athlete has been an ever-present since the race was first held in 2002 and has never finished outside the top ten.

Scottish Athletics reported:

Scottish Marathon Masters results:

Lisa Finlay (Dumfries RC – 2.59.14), Gail Murdoch (Carnegie H – 3.09.37), Erica Christie (Bellahouston H – 3.18.29).

Kerry-Liam Wilson (Ronhill Cambuslang H – 2.31.06), Grant Wilkie (Corstorphine AC – 2.42.55), Roger van Gompel (Dundee HH – 2.46.12).

2012

Ross Houston destroyed a field of 3,960 competitors to win yesterday’s Baxters Loch Ness marathon at Inverness and in doing so the 32 year-old Central AC athlete picked up the Scottish men’s title for the second year in a row.

The race got off to a flying start with German athlete Oleg Ranzow setting a hot pace which only Houston tried to match. After five miles, however, Ranzow began to fall back leaving Houston with the unenviable task of running the rest of the route on his own from the front. He battled on bravely to complete the course in 2hours 20 mintes 24 seconds which was just 11 seconds outside the course record set by Kenya’s Simon Tonui in 2009.

Houston said:”We were doing five minute miling for the first few miles which was probably too fast. I was on my own after about four or five miles, and that was quite hard, but despite that I still thought I could get under 2hr 20mins. From about the 20 mile mark, however, I found it hard and I just wanted it to be over. But it’s another step forward for me and it’s great to win this race and the national title.”

Ranzow paid for his early exuberance and finished 13th in 2:50:27.

Aberdeen’s Ben Hukins came through to take second position in 2:29:17 after a hard battle with Ronhill Cambuslang’s Kerry-Liam Wilson who picked up the bronze medal in 2:30:36.

Hukins said:”It was tough. I realised after about 10 miles that I wasn’t going to get the time I was hoping for, so I just concentrated on finishing as well as I could. Kerry-Liam caught me at 22 miles so I had to work hard to get away from him again to get second position.” Ben Hukins had previously had success on the track, having won four Scottish Championship bronze medals: one for 1500m and three for 10,000m.

Terence Forrest from Grantown on Spey won the Gerald Cooper Memorial Trophy for the first Highland runner to complete the marathon. Forrest recorded 2:48:34 for 10th position.

Avril Mason (Shettleston Harriers) ran a well-judged race to win the Scottish Women’s Marathon title in 2:54:54 which is a lifetime best by 23secs. She also won the Scottish Masters gold medal.

She said:”I’m pleased to win, but to be honest I was hoping for a quicker time. The pace was too fast early on. I ran with Lisa Finlay and Jill Knowles for the first nine miles. I got away from Jill around the halfway mark and I was clear of Lisa after about 17 miles. It’s nice to win the Scottish title as it’s my first championship medal, and to be quite close to a personal best time is also pleasing.” Avril also won Scottish Masters titles in 2014 (Half Marathon) and 2015 (10 miles).

Finlay (Dumfries Running Club), last year’s winner, had to settle for the silver medal on this occasion, but took some consolation from running her fastest ever marathon time of 2:57:55. She said:”I’m inside my personal best but I don’t think I ran too well as I started too fast and I was hanging on towards the end. “Avril ran beautifully and judged it very well.”

Jill Knowles (Scottish Prison Service AC) took the bronze medal when recording 3:03:07 on her marathon debut.

Erica Christie (Bellahouston Harriers), who has now competed in all 11 Baxters Loch Ness marathons, maintained her fine record in the race by finishing first in the over-50 age group, 11th overall, in the women’s division of the race with a time of 3:12:46.

Ross Houston in the 2014 Commonwealth Games Marathon

Ross Houston has had an excellent running career. As a member of Central AC (and Aberdeen University) he played a big part in Central’s team wins in the National Cross-Country Championships – in 2011, 2012 (when he won individual bronze), 2013 and 2015. Ross won the Scottish 10k title in 2011; and the Scottish Half Marathon in 2012. Concentrating on the marathon, in 2013 he ran 2.18.28 in Frankfurt. In 2014 Ross ran for Scotland in the Glasgow Commonwealth Games Marathon, finishing 16th in a good time of 2.18.42. His Scottish team-mate, Kilbarchan’s Derek Hawkins, was ninth (2.14.15) and first Briton. Then in 2015, Ross Houston tried ultra-distance and was an immediate success: racing to a clear win (6.43.35) in the Anglo-Celtic Plate 100km, which won him not only the Scottish title but also the Home Countries International match.

Scottish Athletics reported:

Scottish Marathon Masters results:

Avril Mason (Shettleston H – 2.54.54), Lisa Finlay (Dumfries RC – 2.57.55), Jill Knowles (Scottish Prison Service – 3.03.07)

Kerry-Liam Wilson (Ronhill Cambuslang H – 2.30.36), Marcus Scotney (Hoka – 2.32.28), Scott Bradley (Carnegie H – 2.34.36).

2013

Kenyan Tarus Elly was in commanding form as he cruised to an impressive victory ahead in yesterday’s Baxters Loch Ness marathon. The Manchester-based athlete, who comes originally from the western Kenyan village of Eldoret which has produced so many world class distance runners over the years, was making his marathon debut.

The 28 year-old never looked to be in any danger of losing and although his winning time of 2hr 27min 21sec was more than seven minutes outside the course record set by his compatriot Simon Tonui in 2009, Elly looked as though he is capable of running faster in the future.

He said: “I was very cautious at the start because it was my first marathon. But after six miles I was feeling good and I thought that the other guys wouldn’t be able to stay with me. I began to pull away and ran the rest of the race on my own. Before the start I was looking for a time of between 2:28 and 2:30, so I am very happy to get 2:27. The course is really good and I couldn’t believe how perfect the conditions were. It was amazing. Now that I’ve done my first marathon I know what it’s all about and I’d really like to come back next year and hopefully run much quicker.”

Edinburgh University’s Patryk Gierjatowicz, picked up the Scottish marathon title when finishing runner-up in 2:30:39. The postgraduate maths student becomes the first Polish athlete to win the national title. Although delighted to win the award Gierjatowicz was disappointed with his time.

He said: “I’m pleased to be Scottish champion but my time wasn’t so good as its about four minutes outside my best. I slowed down quite a lot over the final two miles. It’s frustrating because I have been injured recently and wasn’t able to do all the training I wanted to do.”

Ross Clark (Hunters Bog Trotters – 2.36.05) smashed his previous best time to finish in third position overall and second in the national championship. He said:”I can’t believe it. I’ve taken seven minutes off my previous best time which I set at Rotterdam last year. I’ve trained really hard for this race and I was aiming for a place in the top ten but to finish third and win a national medal is just amazing. I had an added incentive as I was also running to raise funds for Yorkhill children’s hospital as my nephew was looked after there and I wanted to support their work.” Roger Van Gompel (Dundee Hawkhill Harriers – 2.36.35) won Scottish bronze.

Megan Crawford (Fife AC) enjoyed a marathon debut to savour by setting a new course record of 2hr 46min 37secs to win the Baxters Loch Ness marathon women’s title and the Scottish championship gold medal. The Edinburgh-based runner shaved two secs off the previous leading mark for the course set by Ethiopia’s Dinknnesh Mekash Tefara in 2010. Crawford pulled away from Romanian favourite Alina Nituleasa after the halfway mark and went on to win by more than three minutes.

She was ecstatic about winning the race and collecting her first national title. She said:”I had absolutely no expectations as it was my first marathon but it’s a nice feeling to win. I knew I was running well in the lead up to the race as I finished third in the Moray half marathon recently. After that I felt I could run a decent marathon time but I had no idea how it might go. I ran with the Romanian runner until around the halfway point when I began to get away and from there on I just kept going.”

Nituleasa was well below her best when finishing second in 2:50:21. The Romanian blamed her exhausting travel arrangements for contributing to the result. She said:”I had a three hour train journey from my home to the airport, then a three hour flight to London. Then I was on a bus for 13 hours to get here. In all, it took me 26 hours so I was very tired.”

Lisa Finlay (Dumfries), who won in 2011 and was runner-up last year, finished in third position in 2:52:25, but she was delighted with the outcome. She said:”I’ve got to be pleased because it’s a personal best time by more than two minutes.”Lisa was also first in the over-40 age division of the Scottish championship and second overall.

Carole Setchell (Shettleston Harriers), who was second in 2011, set a personal best time of 2:57:10 to take the Scottish bronze medal when finishing fourth overall.

Patryk Gierjatowicz (907) racing hard in an Edinburgh University vest.

2013 RESULTS BAXTERS LOCH NESS MARATHON

Men: 1 T. Elly (Salford) 2hr 27min 21sec; 2 P. Gierjatowicz (Edinburgh University) 2:30:49; 3 R. Clark (Hunters Bog Trotters) 2:36:05; 4 R. Van Gompel (Dundee Hawkhill Harriers, over-40) 2:36;35; 5 R. Smith 2:37:39; 6 A. Simpson 2:41:42; 7 W. Dashper 2:42:22; 8 R. Spooner 2:43:21; 9 C. Hill (Cosmic Hillbashers) 2:43:43; 10 A. Rouse (Edinburgh AC) 2:44:02. Over-40: 2 R. Harrison 2:51:35; 3 A. Howlett 2:52:12.

Over-50: 1 P. Davies 2:48:42; 2 A. Kot 2:58:21; 3 T. Coyle 3:02:46. Over-60: 1 R. Blake 3:19:15; 2 T. Summerscales 3:41:46; 3 G. Arthur 3:43:13.

Women: 1 M. Crawford (Fife AC) 2:46:37; 2 A. Nituleasa (Romania) 2:50:21; 3 L. Finlay (Dumfries, over-40) 2:52:25; 4 C. Setchell (Shettleston) 2:57:10; 5 J. Malko (Corstorphine) 2:58:30; 6 J. Emsley (Central AC) 2:58:40; 7 J. Gordon (Kinross) 3:02:23; 8 C. Black (Shetland) 3:04:31; 9 V. Hunter 3:07:25; 10: K. Morgan 3:08:22. Over-40: 2 G. Beaton 3:10:25; 3 B. Gibson 3:11:13. Over-50: 1 I. Burnett (Carnegie Harriers) 3:17:13; 2 E. Christie (Bellahouston) 3;18:48; 3 C. Catterson (VP Glasgow) 3:20:13. Over-60: 1 J. MacLeod (Metro Aberdeen) 4:04:28; 2 L. Gray (Inverness) 4:20:59; 3 E. Hendry 4:24:19.

Scottish Athletics reported:

Scottish Marathon Masters results:

Lisa Finlay (Dumfries RC – 2.52.25), Jillian Gordon (Kinross RR – 3.02.23), Charlotte Black (Shetland AAC – 3.04.31).

Roger van Gompel (Dundee HH – 2.36.35), Adam Rouse (EAC – 2.44.02), Barry Paterson (Falkirk VH – 2.49.26).

2014

Manchester-based Tomas Abyu returned from a lengthy spell of training in Ethiopia to claim his fourth Loch Ness Marathon title in fine style today (Sunday 28th September)

The African athlete looked composed throughout the 26.2 mile race which started on the high ground between Fort Augustus and Foyers and followed a route along the south shores of Loch Ness before finishing at the Bught Park in Inverness.

Abyu, who is a former Great Britain international, sprinted strongly through the finishing tape in 2hr 22min 41sec to add to his previous victories in 2003, 2010 and 2011.

He said: “I’ve been training in Ethiopia for a long time and I only returned last week when I decided to do the race. I felt quite easy for the first 16 miles, then it got tougher, but I had been able to pull away from the others before halfway so I just kept it going.

“I like running here. The countryside is very nice and it’s a good course. I certainly want to come back again next year to defend my title. In the meantime I hope to recover quickly so I can do the Yorkshire marathon in a couple of weeks from now.”

Edinburgh-based Polish athlete Patryk Gierjatowicz (Hunters Bog Trotters) collected the Scottish title for the second year in a row when finishing in the runner-up position in a personal best 2:24:17, while last year’s Loch Ness champion Tarus Elly (Salford) was third in 2:25:37.

With neither Abyu nor Elly being eligible for Scottish medals, the national silver went to Kerry Liam-Wilson (Ron Hill Cambuslang Harriers), who was fourth overall in 2:28:56 and the bronze was collected by John Sharp (Inverclyde AC) who was fifth in 2:31:58. Wilson also won the over-40 age group title.

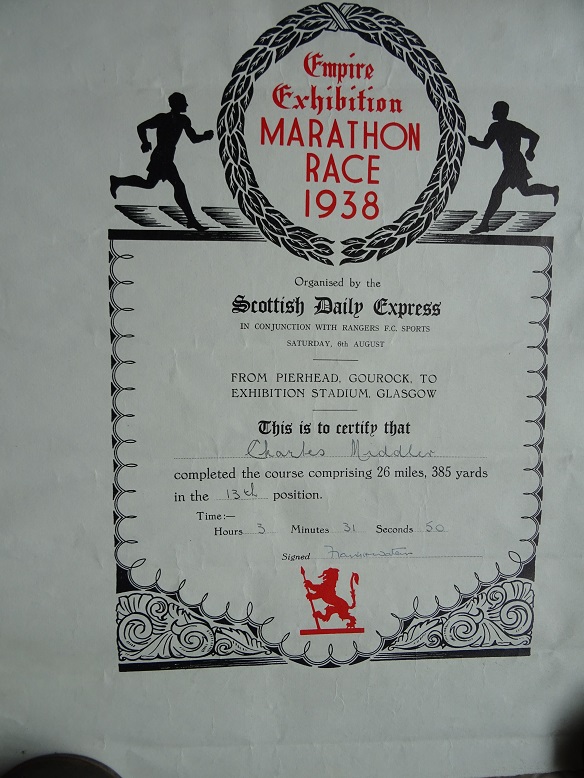

Kerry-Liam Wilson has been the outstanding M35/M40 Scottish Veteran Harrier for several years. Kerry has won: five BMAF titles (two cross-country, ten miles, 10k and 5k); 24 Scottish Masters championships (including three marathon titles); and nine SVHC. In 2015, he contested the World Masters Marathon in Lyon, France, finishing fourth overall (3rd M40) after a truly valiant effort. He was first Briton and helped GB to team silver. He runs huge mileages in training and deserves every success.

As a Senior, Kerry-Liam won bronze medals in the Scottish Marathon championship in 2011 and 2012; before improving to silver with a personal best 2.28.58 in 2014. He also won bronze in the 2013 Scottish Half Marathon Championship.

Kerry-Liam Wilson in the 2015 World Masters Marathon

There was a dramatic finish to the women’s race in which Jenn Emsley (Central AC) held off a late challenge from title-holder Megan Crawford (Fife C) to take the top prize in a new course record time of 2:46:10, knocking 27secs off the previous standard. Crawford was also inside the old record, which she set twelve months earlier, when finishing just 15 secs behind, while Shona McIntosh took the bronze in 2:53:15.

Emsley was delighted with her day’s work which in addition to the record yielded a Scottish title, a personal best time and a winner’s cheque for £1,500.

She said: “I am very happy but surprised to have run a quicker time than I did at the London marathon, as I think Loch Ness is a harder course. But my training had been going well and I feel I’ve finally justified the hard work I’ve been doing.”

“There were four of us for the first 10 miles then the Romanian runner, Alina Nituleasa, dropped back. Megan then seemed to drop back and I eventually pulled away from Shona. Then, near the end, I could see that Megan was beginning to close up on me again so it was just a case of keeping going and not getting caught.”

Crawford had mixed feelings about her performance which was admirable given that she suffered from stomach problems throughout the race. She said: “I’m a bit annoyed but at the same time I’m really happy for Jenn. I had to stop so many times during the race because of my dodgy tummy and every time I got going I was trying to make up ground. I eventually got past Shona and then began to close on Jenn. I am convinced that if there was another mile I might have caught her.”

Jenn Emsley and Patryk Gierajatowicz: 2014 Scottish Marathon Champions

Terry Forrest (Cairngorm Runners) won the HSPC Gerald Cooper Memorial Cup, presented to the first Highland runner, for the third year in a row when he completed the course in 2:39:13. This was an impressive performance given that he started at the very back of the field.

Erica Christie (Bellahouston Harriers), who has competed in all 13 Baxters Loch Ness marathons, maintained her fine record of consistency by winning the over-50 women’s title in 3:14:20.

Scottish Athletics reported:

Scottish Marathon Masters results:

Beverley Gibson (Fife AC – 3.07.57), Gail Murdoch (Carnegie H – 3.08.52), Erica Christie (Bellahouston H – 3.14.17).

Kerry-Liam Wilson (Ronhill Cambuslang H – 2.28.56), Scott Bradley (Carnegie H – 2.35.44), Russell Whittington (Bellahouston RR – 2.43.19).

2015

Record-breaker Megan Crawford was in exuberant mood after winning the women’s title in today’s Baxters Loch Ness marathon. The Fife AC runner completed the scenic Highland course in a time of 2hrs 44min 50secs to obliterate the previous women’s record of 2:46:10 set by Central AC’s Jenn Wetton last year when Crawford finished 15secs behind in second position.

Megan Crawford celebrates her 2015 victory

Belgrave’s Gatenesh Tamirat, the 2014 Jersey marathon champion, finished second in 2:57:44 with Shona McManus (Kelvin Runners – Scottish silver medal) pipping Gillian Sangster (Dundee Road Runners – Scottish bronze medal) by 41secs to take third spot in 3:02:06.

Crawford, who improved her fastest marathon time to 2.40.26 in London this April, pocketed the Scottish title for the second time in three years and was ecstatic with this result. She said: “I love this marathon. It’s definitely one of my favourites and I was actually having fun out there. One of my main motivations for doing it was to try to win the Scottish title again and I’ve done that so I’m very happy.

“I ran with Gatenesh for the first 17 miles. I was reluctant to go in front before then so I just stayed with her. I’d thought about making my move on the hills after about 19 miles, but then decided to push on a bit earlier than that. When I made my move she didn’t stay with me for too long so I kept pushing and decided that if I fell apart it would just be my own fault. But I was fine and I knew I was on track for a good time so I kept it going. I’m hoping to do the half marathon in Glasgow next week so I hope I recover quickly.”

Tarus Elly, who returned from visiting family and friends in Kenya four days earlier, won the men’s race for the second time in three years. The tall African, who has been living in Hyde for a number of years, was only a few seconds outside his best time when sprinting home in 2:25:19.

Four-time previous champion and title-holder Tomas Abyu, from Salford, had to settle for second position in 2:27:37 while Edinburgh-based Patryk Gierjatowicz (Hunters Bog Trotters) collected the Scottish national title for the third year in a row when finishing a further 10secs behind. Kenyan athlete Benjamin Bartonjo, who was expected to be a strong contender for the top prize, never appeared.

Patryk and Megan on the podium

Elly said: “I spent a month at my old home at Eldoret in Kenya and only got back on Thursday so I’ve not at much time to get acclimatised to being back here. When I was in Kenya I didn’t train as much as I planned because I spent a lot of time visiting people. But I’m pleased with my run today. This is one of my favourite races so I always like to do it. When I first came her two years ago I won and last year I was third.

“It started at a steady pace and I was with Tomas and Patryk for the first 10 miles. Tomas then opened a gap but I just kept an eye on it and didn’t let it get any bigger. At 22 miles I closed up on him, pushed on a bit and I could tell he wasn’t able to come with me. By 23 miles I was ahead and just kept it going.

“I never realised I was so close to my personal best time. I was just pleased to be winning the race but if I had known the time, I might have pushed on a bit more.”

Fourth-placed John Newsom (Inverness Harriers – 2.32.54) won the Gerald Cooper Memorial Cup which is presented to the first Highland runner to finish the marathon. The sponsors of the award, HSPC, will now make a £1000 donation to a charity of his choice. Newsom also took second position in the national championships while his clubmate Donnie Macdonald collected bronze when finishing fifth overall in 2:33:28.

John Newsom won Scottish Championship medals, not only in the Marathon but also in the 10k road, Half Marathon and Senior National Cross Country.

Scottish Athletics reported:

Scottish Marathon Masters results:

Gillian Sangster (Dundee RR – 3.02.47), Gail Murdoch (Carnegie H – 3.07.40), Dorothy Mathie (Portobello RC – 3.12.39).

Russell Whittington (Bellahouston RR – 2.44.39), Crispin Walsh (BellaHouston H – 2.45.20), Alasdair Campbell (Moray RR – 2.50.34).

24/04/2016 London Callum Hawkins Kilbarchan AAC 2:10:52 Tsegai Tewelde Shettleston H 2:12:23 Derek Hawkins Kilbarchan AAC 2:12:57

24/04/2016 London Freya Ross Edinburgh AC 2:37:52 Lesley Pirie VP City of Glasgow 2:41:13 Gemma Rankin Kilbarchan AAC 2:46:34

At the 2016 London Marathon (and Scottish Championship), his second event over the distance, Callum Hawkins finished eighth overall, and was the first British-qualified athlete to finish, in a time of two hours 10 minutes and 52 seconds (a Scottish Marathon Championship Record). This time was inside the qualifying time of two hours 14 minutes needed to earn him a place in the Great Britain team for the 2016 Summer Olympics to be held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He was joined in the men’s marathon by fellow Scottish athletes, Tsegai Tewelde and his brother Derek Hawkins.

Callum Hawkins finished ninth in the marathon at the 2106 Olympics in a time of 2:11:52.

Freya Ross, who represented GB at the 2012 London Olympic Marathon, won her first Scottish Marathon title.

Scottish Athletics reported:

The Scottish Marathon Championships were held within the Virgin Money London Marathon at the weekend and we’ve already mentioned the three Senior medallists for Men and Women with Callum Hawkins and Freya Ross taking the titles.

It was gold success on the team front for Edinburgh AC in the Men and Fife AC in the Women’s race with the cumulative times (rather than positions) the scoring system for the Scottish Marathon. Champs. Edinburgh AC also took the bronzes in the Women’s race.

Here are the Results:

Men’s team: 1 Edinburgh 7:53.50 Neil Renault 2:23.31, Joshua Arthur 2:37.35, Keith Dunlop 2:52.44;

2 Hunters Bog Trotters 7:56:34 Patryk Gierjatowicz 2:24:00, Dave Ward 2:36:57, Michael Taylor 2:55.37;

3 Bellahouston Road Runners 8:16.54 Russell Whittington 2:43.54, Greig Glendinning 2:45.05, Robbie Hayman 2:47.55.

Women’s team: 1 Fife AC 9:23.30 Katie Jones 2:58:02; Hilary Ritchie 3:12.34; Alison McGill 3:12.54;

2 Carnegie Harriers 9:26.26, Joanna Murphy 3:04.45, Gail Murdoch 3:09.23; Kirstin Lownie 3:12.34;

3 Edinburgh AC 9:43.32 Tanya shields 3:04.23, Elaine Davies 3:17.39, Nicki Gibon 3:21.30

Scottish Marathon Masters results:

Men: 1 Jeremy Rossiter (Skye & Lochalsh) 2:29.41; 2 Stephen Allan (Kirkintilloch) 2:38.11; 3 David Cole (Cambuslang) 2:39.08

Women: 1 Marie Baxter (Garioch) 2:57.22; 2 Gail Murdoch (Carnegie) 3:09.23; 3 Yana Thandrayen (Portobello RC) 3:12.21

23/04/2017 London Robbie Simpson Deeside R 2:15:04 Craig Ruddy Inverclyde AC 2:22:22 Andrew Lemoncello Fife AC 2:24:11

23/04/2017 London Susan Partridge VP City of Glasgow 2:37:51 Fanni Gyurko Central AC 2:41:29 Katie White Garscube H 2:42:39

Susan Partridge, who had run for GB in European and World Championship marathons (and for Scotland in the Commonwealth Games marathon) won her second Scottish Marathon title. Katie White, a top-class Scottish and GB W35 cross-country champion, had every right to be pleased by her marathon debut.

Fraser Clyne reported in the Aberdeen Press and Journal:

“Robbie Simpson will spend a couple of weeks relaxing with his family in the peaceful setting of Finzean on Deeside after achieving a Commonwealth Games and World Championship qualifying time of 2hr 15min 04secs when finishing 15th overall and second Briton in Sunday’s Virgin London marathon.

The 25 year-old Deeside Runners club member, whose performance was a personal best time, knocking 34sces off the mark he recorded on his debut at London last year, also picked up his first Scottish senior men’s marathon title in the race.

Now he can now look forward to a return trip to the UK capital in August for the world championships where he’ll be joined by fellow Scot Callum Hawkins (Kilbarchan AAC) who was pre-selected.

Welshman Josh Griffith, who finished 15secs and one place ahead of Simpson, is the third man on the Great Britain team.

Simpson will, however, have to wait until later in the year to find out if he has done enough to earn a place on the Scotland team for the 2018 Commonwealth Games at Australia’s Gold Coast.

Although he had been hoping to run even faster, Simpson admitted to being pleased with the outcome.

He said: “I’m happy to qualify for world championships as I thought I only had an outside chnace given who else was running in the race.

“I would rather have had a faster time but the early pace was too fast and we paid for that later on. I was in a group of about eight and we had a pacemaker aiming to go through halfway in around 67mins which would have been perfect.

“But we were about 30secs too fast at 10km which was too much. I had to stay with the group but most of them slowed down in the second half.

“I was able to run with Josh Griffith from about 10 miles onwards and sometimes he would be ahead, other times I would be in front. At the end I couldn’t quite stay with him. I felt tired from about 15 miles and it was hard, but I was able to just keep pressing on.

“I knew we were the first two Brits and if I could hold on I would be guaranteed a place in the Worlds.”

Simpson hopes to recover quickly before returning to Mittennwald in Germany where he has been based for the past couple of years.

He said:”There’s not really a lot of time between now and the world championships so I’ll need to think through my preparations.

“I’ll probably talk with Callum (Hawkins) as he had a similar period of time between getting Olympic selection at London last year then performing really well at Rio later in the summer.

“I’d be interested to hear what he did. I don’t think I have to change my training very much and I’m not sure if I need to do many other races.

“When I go to London in August I’m going to try to pace it better. There will be less pressure to go chasing a time so I’ll concentrate on trying to keep to an even pace and hopefully I’ll feel stronger until later in the race.”

Having achieved world championship selection, Simpson is also keeping his sights on the possibility of a 2018 Commonwealth Games place, having satisfied the Scotland qualification requirement of running faster than 2:15:30.

He said:”The other Scots guys who I thought might be contenders didn’t do so well in London. Andrew Lemoncello fell right back and ran a slow time while Tewolde Tsegai dropped out.

“Hopefully my time will be good enough but the qualification period doesn’t end until October.”

Robbie Simpson, a world-class GB mountain runner, was selected for the 2017 World Championships but was injured and couldn’t take part. However, his London 2017 performance ultimately earned him selection for the 2018 Commonwealth Games Scottish team. He won a fine bronze medal in the marathon.

Scottish Athletics reported:

Scottish Marathon Masters results:

Lisa Finlay (Dumfries RC – 2.58.13) from Mairi Stanley (Garscube H – 3.07.13) and Lynne Stephen (Fife AC – 3.15.12).

David Lindsay (Garscube H – 2.37.24) from Keith McIntosh (Wimbledon W – 2.38.20) and Louis O’Hare (Kirkintilloch O – 2.38.44).

29/04/2018 Stirling Michael Wright Central AC 2:29:19 Patryk Gierjatowicz Hunters Bog T 2:33:10 Tom Roche Insch Trail RC 2:33:38

29/04/2018 Stirling Alison McGill Fife AC 3:02:35 Michelle Mackay Dundee RR 3:05:01 Rhona Anderson Dunbar RR 3:09:56

Fraser Clyne reported for the Aberdeen Press and Journal:

“Oldmeldrum athlete Tom Roche was overjoyed to pick up two national medals when making his marathon debut in the Scottish championships at Stirling.

The Insch Trail Running Club member posted a time of 2hr 33min 38secs when striking bronze behind Central AC’s Michael Wright, who won in 2:29:19, and Edinburgh-based Polish athlete Patryk Gierjatowicz who was runner-up in 2:33:10.

Roche, winner of the 2017 Dyce half marathon, also scooped over-40 age group gold to complete a very successful first attempt at the distance.

He said: “It surpassed all my expectations. I was hoping for a time of under 2:40 and if all went well I would have been happy with 2:37. I never believed I could go under 2:35.

“Then to get bronze in the national championships and first in my age group was a real bonus. It’s all a bit of a dream.”

Roche paced the race to perfection, working his way through the field and running the second half of the course faster than the first half.

In the closing stages he briefly overhauled two-time previous Scottish champion Gierjatowicz to move into the silver medal position but the Pole responded and regained the advantage.

Roche said: “I was running with a couple of guys to begin with but after about eight miles I was feeling good so decided to push on. I managed to get myself into third position just after the halfway point.

“But after 15 miles Donnie Macdonald from Inverness Harriers caught up with me and we were engaged in a cat-and-mouse battle until about 21 miles when I pulled away.

“Then I could see Patryk ahead and I caught him at about 24 miles. He looked shocked but was able to respond and pulled away from me again. I tried to stay with him but my legs were very tired and I slowed a bit over the final two miles although I was safely clear in third position.”

Donnie Macdonald, who had competed in the Manchester marathon earlier in the month, finished fourth in 2:37:09.

Alison McGill (Fife AC) won the women’s title in 3:02:35.”

Scottish Marathon Masters medallists:

In the men’s race Tom Roche took the gold as well as the overall bronze. Silver went to Chris Devine (Newry City Runners AC) in 2.38.58 and bronze to David Lindsay (Garscube H) in 2.45.11.

Similarly, on the Masters women’s podium, top place went to overall bronze medallist Rhona Anderson, with silver headed for Julie Gordon (Inverclyde AC) in 3.13.41 and bronze to Shona Donnelly (Bellahouston RR) in 3.15.08.

Garscube Harriers took the men’s gold medals thanks to the efforts of David Lindsay, Ian Thomson and Craig Shields. Silver went to Linlithgow and the bronze to Dundee Road Runners.

28/04/2019 Stirling Michael Wright Central AC 2:29:32 Kevin Wood Fife AC 2:30:52 Donnie Macdonald Inverness H 2:34:19

28/04/2019 Stirling Jennifer Wetton Central AC 2:56:06 Lesley Hansen Inverness H 3:04:50 Rhona van Rensberg Fife AC 3:09:55

Both Michael Wright and Jenn Wetton won their second Scottish Marathon titles.

Scottish Athletics reported:

Scottish Marathon Masters Team medals:

Men’s 1 Inverness Harriers; 2 Fife AC; 3 Moray Road Runners

Women’s 1 Central AC; 2 Linlithgow AAC; 3 Perth Road Runners

Rhona van Rensburg is our Masters gold medallist as well as bronze medallist in the Senior race, under the rules of our Road Running and Cross Country Commission for national championship road events. The other Masters medallists were Allie Chong of Giffnock North AC (3.23.40) and Elspeth Jenkins of Moray Road Runners (3.23.42).

Following home the Inverness athlete Donnie Macdonald, the other Men’s Masters medallists were Paul Monaghan of Greenock Glenpark Harriers (2.40.13) and Alasdair Campbell of Moray Road Runners (2.49.07).

Rhona Anderson (Dunbar RR – 3.12.08) won the V50 Women’s gold, with the other medals there for Shona Young of Lothian RC (3.31.33) and Sandra Band of Bellahouston Road Runners (3.54.48). Andy Alexander of Moray Road Runners (3.02.18) took the Men’s V50 gold with the other medals there for Gordon Dryden of Bellahouston Road Runners (3.09.54) and Bruce Taylor of Garioch Road Runners (3.10.21).

In the Men’s V60 category, there was gold for John Robertson of Peterhead AC (2.34.19), silver for Garry Henderson of Moray Road Runners (2.40.18) and bronze for William Sutherland of (Whitemoss AAC – 2.49.07). Timothy Kirk (Kidderminster and Stourport) is our V70 champion (3.38.34).

The Daily Record reported:

“Organisers of the Stirling Marathon were this week in the firing line over cash prizes for race winners and a medals bungle.

Jennifer Wetton, who won last month’s women’s marathon, has hit out after receiving just £200 as the prize. That’s 80 per cent less than the £1000 won by the male and female marathon winners in last year’s race.

The row erupted just a day after it emerged some runners in the Stirling Marathon and half marathon crossed the finishing line and were presented with the wrong medals.

Some of the medals handed out to runners congratulated them for finishing events in Manchester and Bristol rather than Stirling.

Mrs Wetton, a sales co-ordinator with Norbord, was less than impressed with her winnings from the organisers, the Great Run Company.

The 32-year-old, from Wallace Park, said: “Before the race, the prize structure wasn’t available from the information tent the day before the race. The only information that could be given was that there would be a meeting that night to decide the prize money and athletes could come to the information tent on the morning of the race to find out the decision.

“I’m not sure if this was actually possible as on race day morning as anyone with chance of winning a prize was busy preparing to run rather than going to the information tent.

“In 2018, the winners were awarded £1000 so we could only assume that it would be similar this year. However, after winning the race, posing for photos covered in the main sponsor’s branding and speaking to the press positively about the event, we found out, via email, that the 2019 winners were only getting £200. Obviously, I was disappointed with this and couldn’t understand why the prize money had been cut so dramatically. Great Run justified it by saying they were bringing it in line with their other non-televised events. Stirling is the only full marathon that Great Run organise. While £200 is a reasonable sum for a win in a 10k event, it is lower than a lot of half marathons pay and significantly lower than other marathons.”

To add insult to injury, it was also discovered that winners of the men’s and women’s half marathon races received the same prize money as the full marathon winners.

Mrs Wetton added: “Great Run say that they view both distances and the participants in each to have equal standing. Yet the entry fee for the half is only £36 compared to £58 for the marathon. Without meaning any disrespect to the half marathon runners, a full marathon is significantly harder than a half marathon and requires a lot more training. It’s double the distance – I can’t understand how both races can have equal standing. Had I run the half marathon, I could have been racing again this weekend but as I ran the marathon I’ll spend the next four to eight weeks recovering.

“I would like to have known the prize structure in advance so that I could have made a more informed decision when planning my 2019 racing calendar.

“When the race is on the same weekend as London and in the same month as many other high profile marathons, Stirling will need to offer more incentive if they want to attract quality athletes. Great Run are a business though so are probably more concerned with profit than having fast times winning their non-televised races.”

A spokesperson for the Great Run Company said; “Prize money for the Great Stirling Run was brought in line with our other non-televised events in 2019. We apologise that this information was not publicly available sooner and it was an oversight on our part that it was not posted on the website before the event.

“The prize structure for 2018 was removed after last year’s event and we reserve the right to change our prize structure from year to year. The following statement was in place on our website, which we believe made it clear that we were changing the structure for this year. Prize money is available for British athletes at this event but is yet to be confirmed for 2019.”

A Stirling Council spokesperson said: “Prize money for the winners of the Great Stirling Marathon is decided exclusively by the event organisers and is not a matter for Stirling Council’s consideration.

“We have the utmost respect and appreciation for all participants in the Stirling Marathon events – whether they’re running to support a charity or to beat a personal best record – and we are proud to welcome them to our wonderful city.”

Runners lining up for the Edinburgh Marathon, later this month, will be competing for a £1000 cash prize.

Second and third placed runners will pocket £700 and £350 – more than Mrs Wetton and Michael Wright collected for winning their races. Entry for the Edinburgh Marathon costs £60.

In previous years, athletes running in the Balfron 10k received prizes with a monetary value of up to £250.

Winners of the London Marathon, which was staged on the same day as Stirling’s event, won £39,000 for first place, £22,000 for second, £16,000 for third and £10,500 for fourth.

In relation to the medal bungle, the Great Run Company said: “We are aware of a very small number of runners who received the wrong medal at the event. Anyone who has not already been in touch to let us know can contact info@greatrun.org and we will send them a replacement directly.”

2020 Stirling (and Scottish Championship?) Marathon was cancelled due to the Covid Pandemic, as were the 2021 and 2022 Scottish Championships.

“The decision to switch the 2020 Stirling Marathon from spring to autumn will give local and national runners more flexibility to prepare for the course in a packed events calendar, and should allow more people the opportunity to take part in what is a popular event located in Scotland’s historic heartlands.

The 2020 event will take place on the same course as 2019, with slight refinements along the route with a half marathon also taking place on Sunday 11th October.

Last year’s winners Michael Wright and Jenn Wetton, both of Central AC, also attended the launch. Michael Wright said: “The marathon has had tremendous involvement from local communities, volunteers, charities and runners from all over Central Scotland and beyond. I’m delighted that it’s returning next year. All being well I’ll be trying to complete a hat-trick of wins!”

Jenn Wetton commented “It’s a wonderful marathon course with fantastic supporters along the route. The back drop of Stirling Castle and Wallace Monument make this one of the most awe inspiring runs I’ve ever taken part in. I’m especially pleased that the prize money for elite athletes has been significantly increased to reflect the status and importance of the new look event.”

2023

London

Luke Caldwell claimed the men’s gold in the Scottish Marathon Champs at the TCS London Marathon

And Masters athlete, Sara Green, crowned her remarkable recent achievements by taking the women’s gold with a strong run in London.

Hundreds of Scots made the journey south to savour the renowned atmosphere and the enthusiasm of runners and spectators wasn’t dampened by cool and wet April conditions.

Luke represented Scotland at the 2014 Commonwealth Games on the track and raced for GB and NI last summer in the European Champs in Munich but unfortunately was a DNF on that occasion,

This time he finished sixth in the British Champs event with a run of 2:13.29 in London to head the Scottish podium.

Taking the silver medal will be Weynay Ghebresilasie as the Shettleston Harriers athlete came home in 2:15.41.

Our bronze medallist in the Men’s race is Fraser Stewart of Cambuslang Harriers with the Scottish Half Marathon champion coming up with un of 2:18.34 to improve his PB by six seconds.

Sara Green had an excellent run as she maintained the kind of performance level that has been the norm this past winter in cross country and road running.

The Gala Harriers athlete clocked 2:44.41 and that will land her another share in our Road Race GP.

Germany-based Scot, Natalie Wangler, is the silver medallist after a run of 2:51.09 and the bronze is headed for VP-Glasgow athlete Rhian Dawes. Rhian was home in 2:52.15.

Law and District AAC athlete, Jessica Robson, had a superb run to break three hours with 2:59.27. We make that sixth all-time on a list of UK U20 performances.

It was almost an improvement on close to 10 minutes from marathon debut in Germany last October. Well done to Jess and her coach, Eddie McQuillan!

Commonwealth Games wheelchair marathon silver medallist, Sean Frame, raced the distance for the second time in less than a week.

After competing in Boston last Monday, Sean was back out in the T53/54 event in London and clocked 1:38.43 for 15th place in the race.

Joanna Robertson made her debut and the Aberdeen AAC athlete finished 17th in the Women’s T53/54 in 2:28.16.

In the Scottish Marathon Masters division, Sara Green won W40 gold from Alison McNeilly (Dundee RR – 2.58.53) and Gillian Blee (Garscube H – 3.08.38)

W50 champion was Mairi Stanley (Garscube H – 3.21.26) from Paula Ross (Highland HR – 3.27.51) and Claire McCormick (Bellahouston H3.32.51).

Jacqueline Heilbronn (Dundee RR – 3.48.49) won W60 gold, from Helen Mackie (Forfar RR – 3.55.12) and Shirley Wieland (Bellahouston RR – 4.18.47).

M40 Champion was Jack Letson (Inverness H – 2.31.05) from Graeme Doig (PH Racing Club – 2.33.21) and Colin Thomas (Bellahouston H – 2.33.53).

Tommy Gavin (EAC – 2.39.26) was first M50, from Stuart Robertson (Perth RR – 2.40.33) and Bruce Taylor (Garioch RR – 3.10.21).

First M60 was Alexander Potter (VP City of Glasgow – 3.08.00) from Jeremy Tomlinson (Fife AC – 3.19.51) and John Robertson (Peterhead AC) 3.27.17).

Malcolm Hammond (PH Racing Club – 4.04.47) won the M70 division, from Phill Thompson (Moray RR – 4.41.03.