A YEAR IN THE LIFE: SCOTTISH ATHLETICS IN SUMMER 1985

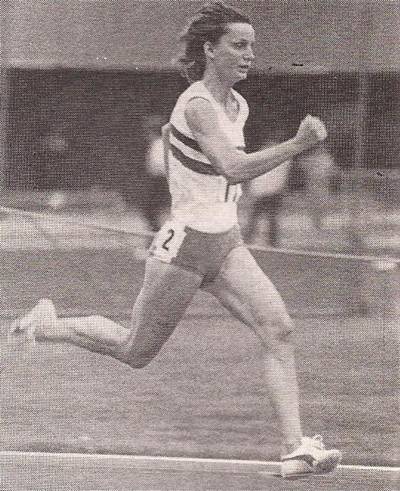

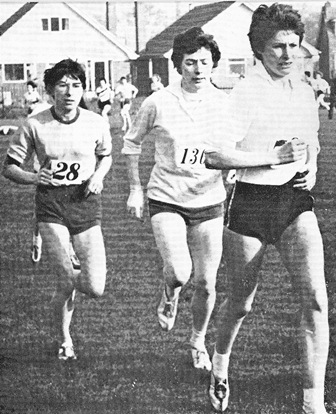

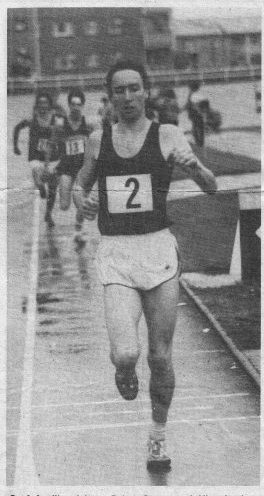

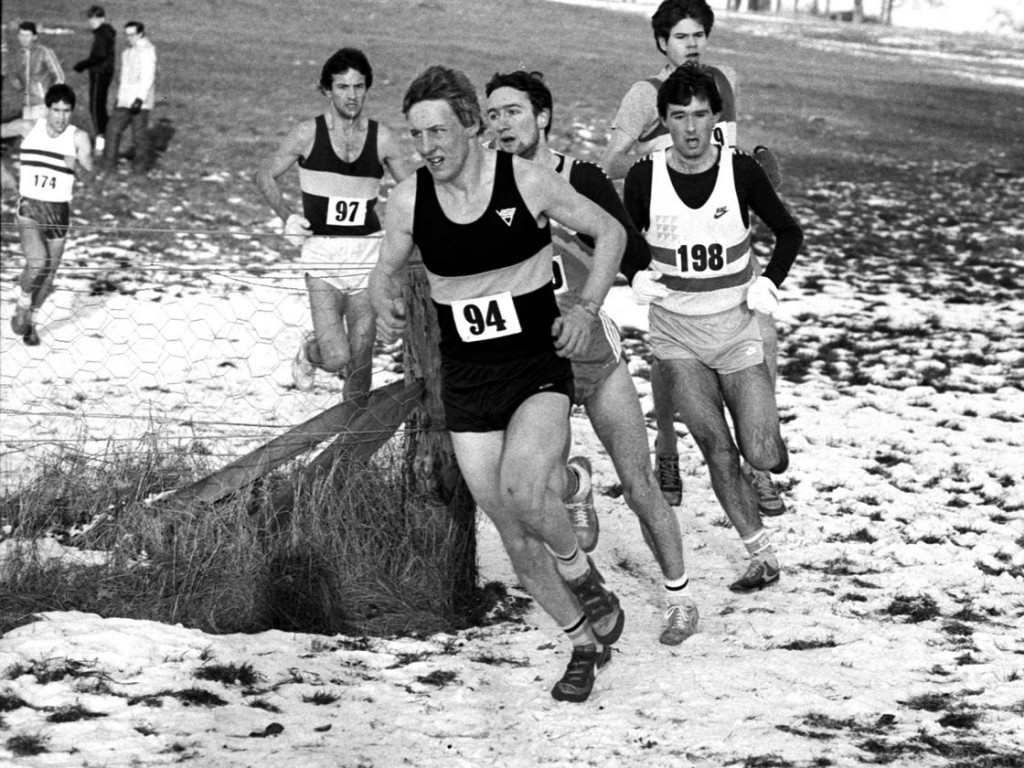

SAAA 1500m Championship, 1985: 37 A Currie, 1 A Callan, 17 J Robson

SAAA 1500m Championship, 1985: 37 A Currie, 1 A Callan, 17 J Robson

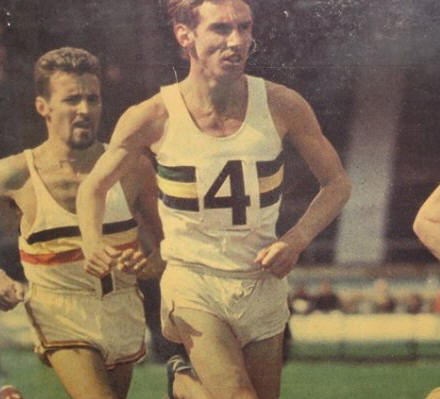

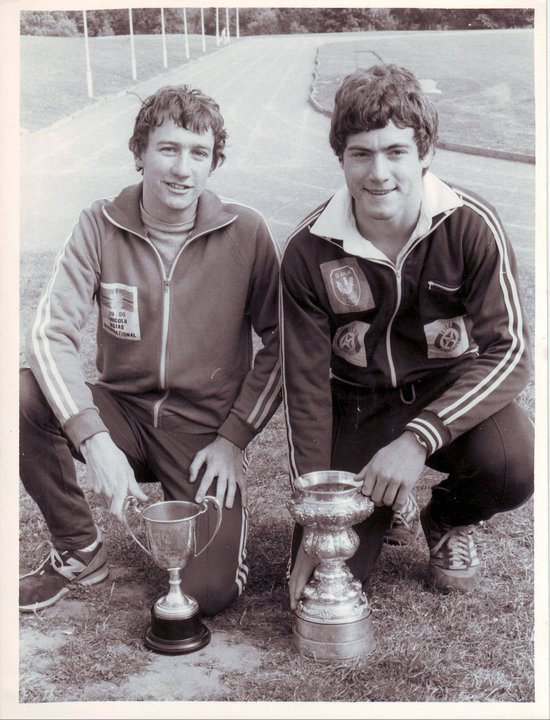

The high point of the 1980’s happened in 1986 and what was almost the low point was in the same year. The high point was the arrival on the scene of the ‘Scotland’s Runner’ magazine which ran from mid-86 to late 1993 and covered ALL of Scottish athletics in some depth. The Commonwealth Games of the same year was but a shadow of the 1970 Games. The financial shambles, the African boycott and the poor representation of Scottish athletes all contributed – a large part was played by the British government (particularly Malcolm Rifkind) but the result of the selectors deliberations also led to a disappointing event. With athletes like McKean, Lynch, Murray, Hanlon, Tennant, Callan, Currie, Robson, Williamson and Hutton at their disposal the team should have been bigger and stronger than it was.

1985 on the other hand was a very good year with athletes hopeful of selection performing often at the top of their game. The shape of the season had been evolving over the decades and the expectations of athletes in 1985 were higher than those of any preceding decade of athletics in Scotland. Physiotherapy, sports doctors, nutritionists and facilities were all more readily available. Performances should have been higher than before too. Assuming 1985 to be more typical of the decade than 1986, we can start our look at the year at the end of April.

The year started with a bang – the Rotterdam and London marathons took place on 21st April and Scots performed nobly in both. In London Allister Hutton finished third in what was only his second marathon in 2:09:16. Lindsay Robertson was 13th in 2:14:59, Jim Dingwall 18th in 2:15:24, Andy Girling was next in 2:15:38 and Andy Daly was 21st in 2:15:47. And Lynda Bain recorded a new Scottish record of 2:33:38. In Rotterdam, John Graham was second in 2:09:58. Two Scots inside 2:10 on the same day. There were three marathons the following week – Lochaber where Colin Martin of Dumbarton won in 2:26.58 (a course record), in Dundee where Murray McNaught won in 2:20:25 and in Galloway where P Haworth of Keswick defeated Mike Batley (VP) by four minutes in a course record of 2:27:10. In the first women’s league match at Meadowbank, Ann Clarkson won the 1500m in 4:32:33.

May is traditionally the start of the summer track and field athletics season and in 1985 there were three track meetings, a half marathon, the Edinburgh to North Berwick 22 miler and Scots running fast times in an invitation meet in Gateshead. The two biggest meetings were the SWAAA East and West District championships. In the East District Championships on Saturday, Shona Urquhart won both discus and javelin – the latter with 50.28m, just two metres short of her national record. Yvonne Murray won the 1500m in 4:22.8 and Karen Macleod won the 3000m in 9:52.8. At the other end of the M8 in Glasgow Sandra Whittaker was the best performer when she won 100 and 200 metres championhips in 12.1 and 242. Carol Sharp won the 800m in 2:10.4, Elspeth Turner won the 1500 in 4:32 and Audrey Sym the 3000m in 10:23.4. The Men’s Track League was now run with all eight teams competing against each other in all four matches and at the first meeting Chris Black, who by now was concentrating on the shot putt, won three events – the the shot (16.27m), discus (45.82) and the hammer with 63.08m. 19 year old Alistair Currie ran 4:04.4 at Gateshead and brother Alan ran 4:09 after doing the pace making. Alan Puckrin ran 14:13.8 when winning the 5000m at the same meeting. Tommy Murray beat 1400 runners in the Cunninghame Centre Half Marathon in 68:28. Robin Morris won his second Edinburgh to North Berwick 22.6 miles road race in 1:57.24. These were all on the Saturday but Yvonne Murray travelled to Glasgow on Sunday for the Gaymers Old English Cyder 3000m through the streets of the city centre. 20 year old Yvonne won in 8:50.88 from Angela Tooby (8:56.7). Lynda Bain was 16th in 9:26, Violet Blair 21st in 9:33 and Christine Price 22nd in 9:36. In the men’s 10000m race Nat Muir was unplaced but ran 28:53, Allister Hutton, recovering from the London Marathon, was 15th in 28:57 and George Braidwood was 19th in 29:05.

The second weekend saw the Scottish Universities championships on the new track at Wishaw, the Pearl Assurance races for men and women in Edinburgh, the Gaymer’s Olde English races in Cardiff, two cup matches – the GRE Cup for men and the Jubilee Cup for women – , men’s GB league matches at Birmingham and Cwmbran, and the Gourock Highland Games. In the University championships, Martin Johnson (Aberdeen) won the 400min a new meeting record of 48.7, and Richard Archer (3:51 – new record) out-kicked Robert Quinn (3:52.4) to win the 1500m after Quinn had led most of the way. Elspeth Turner (Strathclyde) won the 800m in 2:13.6 and ran the next day in the Pearl Assurance Half Marathon in Edinburgh where she won the women’s race in 77:07, two minutes clear of Lorna Irvine (Borders AC). In the men’s race Richard Charleston of Wolverhampton won in 65:54, Lawrie Spence was second in 66:00 and George Braidwood third in 66:09. In Cardiff, Yvonne Murray won the 3000m in 8:54, two seconds clear of Christine Boxer. In the men’s race Nat Muir was top Scot in 27:55 in sixth position. Shettleston won the first round GRE Cup match at Crownpoint in which Brian Scally won the 1500 after Alistair Douglas did a lot of the early work before Alan Puckrin took the role of leader with Scally winning the charge up the finishing straight in 3:53.6 and Puckrin and Douglas both being timed at 3:53.7. In the UK women’s league at Grangemouth Sandra Whittaker had a sprint double winning 100 metres and 200 metres in 12.3 and 24.6 seconds. Adrian Callan won the 3000m at Gourock Highland Games – he was leading with one lap to go when the officials thought the race was over and stopped the race! John Duffy of Greenock Wellpark won the 14 mile road race from Lachie Stewart (15 years after his triumph at Meadowbank) in 71:57 with Lachie winning the first veterans award.

Lachie Stewart: Hero of the 1970 Games in the Stirling Half Marathon: 1985

The SWAAA East v West competition took place on 18th May at Meadowbank and the East beat the West. That was not the talking point however: Lynsey MacDonald had come back from illness and injury to win both the 100 metres and the 400 metres. The 100 was run into a 2.14 metres per second headwind and she clocked 12.39 before turning her attentions to the 400m where she ran 54.14. Trailing Fiona Hargreaves with 100 to go, she came through into the wind to win by one tenth. Yvonne Murray won the 1500m on her own in 4:16.61. There was agreement however that the finest performance of the afternoon was the long jumping of Lorraine Campbell whose 6.31 metres was the best by a Scots woman since the Games of 1970 and the fourth best of all time. The ‘marathon boom’ was in full swing at this time and there was a marathon in Motherwell which was won by Charlie McDougall of East Kilbride AC in 2:26:52 with Ian Moncur from Elgin second in 2:27:26. Glenrothes had a half-marathon which was won by Sam Graves in 69:10 from Jim Ash (Beith). The Goatfell Race was won by Andy Styan of Holmfirsth in 20:12 from Mike Fanning (Keswick)with Paul Dugdale, attending Dundee University, third. In the Scottish Vets 10,000m Albert Smith beat Tony McCall of Dumbarton to win the Glasgow 800 trophy.

The HFC GB Championships were held in Antrim and there were rumours of Irish terrorist plots but they were ignored by most Scots and the results were rewarding. Five winners: Yvonne Murray won the 3000m in 9:00.2 with Liz Lynch third in 9:08.34, just behind Angela Tooby. For her efforts, Yvonne collected £500 which brought her earnings over three weeks to £2200. She also finished third in the 1500 behind Bridget Smyth ( a member of Steve Ovett’s club Brighton Phoenix) to pick up £100. The Scots staged a clean sweep in the women’s 800m with Liz McArthur (Pitreavie) winning in 2:05.5, Karen Steer (Exeter) second in 2:06.3 and SWAAA Champion Carol Sharp third in 2:08.10. In the men’s 800 metres, Tom McKean (described in the Glasgow Herald as ‘a Glasgow labourer’) went through 400m in 54.2 and kicked twice in the last 300m to defeat Steve Cram and win in 1:49.12 – only one second ahead of David Sharp from Jarrow. Geoff Parsons won the high jump with 2.06 and Paul Mardle won the discus. Former professional athlete Gus McCuaig from Helensburgh took two bronze medals in the sprints and Lorraine Campbell from Dumbarton was third in the long jump with three jumps over 6 metres, the best being 6.21m.

Crown Point opened officially on 9th June, 1985 with a big star studded athletics meeting – there was also a large carnival element in the proceedings. Doug Gillon describes the day:

Quality athletics came to Glasgow yesterday with the gala opening of the new £2.3 million pound sports complex at Crown Point Road. The scissors arrived by parachute, bang on target for the Lord Provost’s ceremonial tape cutting. A comedy car and battling Cumberland wrestling giants helped make it a carnival day, and thousands of spectators clearly relished the proceedings. But the athletes were a bit bemused. Not surprisingly perhaps. When the pantomime car back-fired, the women’s 800m runners took off up the track for some 80 metres before they realised their error. Chariots of Fire, indeed! And the giant Cumberland wrestlers had the microphone plug pulled on their act as World and European medallists were forced to delay the start of the Mile.

Even when the Mile did start, the international field seemed to show little appetite to compete. The first lap took a pedestrian 65 seconds, yet the race’s first casualty was ready to drop out. Before halfway had been reached (in 2:06.5), John Robson, the former Commonwealth Games bronze medallist, had gone with a recurrence of a leg injury; Paul Forbes the former UK 800m champion, found a sore throat too much to bear, and Italian visitor Primo Luca, all the way from Turin, simply disappeared. But then with Alistair Currie from Dumbarton taking up the running in admittedly gusty conditions, a real race developed. the third lap took just inside 60 seconds and the final one even faster. But the field had played into the hands of Rob Harrison, European indoor champion at 800 metres earlier this year. Harrison’s pace, with a 58 seconds final 400m, won the day. He clocked 4:04 to lift a £400 prize for his trust fund, Gareth Brown (4:04.7 and £300) and the dogged Currie third (4:06.2 and £200). The 3000m was no less fraught.

Nat Muir’s intended assault on his own native record of 7:56.2 died still-born with the freshening wind. And he was not helped by the fact that Geoff Turnbull (Gateshead) the former Scottish 1500m champion, who could have been counted on to push him hard, never even made it to the starting line and spent his time on the physiotherapist’s couch with a leg injury. Muir at least ensured a respectable race. He took the early pace then settled into the pack as Bingley’s Steve Binns pushed the pace along. With two laps to go, Gary Nagel, trained at Gateshead by Brendan Foster’s former mentor Stan Long, looked set to spoil Muir’s script. The Geordie had a three metre lead on Muir with 200 to go. But the Shettleston Harrier, in classic fashion, came off Nagel’s shoulder entering the home straight, and with the change of pace that marks true class strode home to win comfortably in 8:02.7. Nagel finished second in 8:02.3 and George Braidwood (Bellahouston) produced a spirited kick to outkick Binns and win in a personal best 8:04.7. Down the field junior Robert Quinn (Kilbarchan) also clocked a lifetime best of 8:10.

The Sharps, husband and wife Cameron and Carol, had to settle for second best. Cameron, European 200 metres silver medallist, was held off by Ghanaian Olympic sprinter Ernie Obeng who won the 100m in 10.3. Sharp (Shettleston) just out-dipped Buster Watson, a Los Angeles Olympian last year, both being timed at 10.4 in an assisting wind of 1.2 metres per second. Gus McCuaig (EAC) was fourth in 10.5. In the women’s 200m, the Olympic class of Joan Baptiste (RAF) saw her home comfortably ahead of Jayne Andrews (23.2 to 23.6) with Edinburgh Southern’s Kay Jeffrey third in 23.8. Carol Sharp (McLaren GAC) reigning Scottish champion over 800m, saw a familiar sight among Britain’s top athletes this year – the back of Yvonne Murray. The Edinburgh AC girl, who will bring her winnings this year to more than £5000 when she collects a cheque for £750 today, was a winner again.

She hit the front of the women’s 800m field after 120 metres and ran from the front unchallenged. But Mrs Sharp had to come on strong in the home straight to overhaul Liz Lynch. Miss Murray clocked 2:06.5, her second fastest time ever, Mrs Sharp 2:08.7 and Miss Lynch 2:09.1. This brought another £100 to Miss Murray whose trust fund will get a further £750 today as Musselburgh’s Young Personality of the Year.

Alan Wilson (Victoria Park) won the Glasgow Open 1500m in 3:58.9; Bob Davidson (Coatbridge Health & Strength) the weight over the bar with 13′ 6″ and Walter Weir (Central Region) the caber. In the Heavyweight Tug of War, McAlpine’s defeated Ben Ledi.”

Of course not everyone was at Crown Point and not everyone wanted to be. Under the headline “Proving class runs in the family” Doug covered the Scottish Junior, Youth and Senior Boys Championships at Meadowbank where the headline derived from the double victory by Glen Stewart in the 800 and 1500m events in the Boys age group, and the winning of the 100 metres in the same age group by George McNeill, son of the world renowned former professional sprinter. There were other names on the results sheet which became familiar as the years rolled on – in the Youths age group Gerry McCann won the 800m (1:55.68), Sam Wallace the 1500 (4:05.98) and Alaister Russell the 3000m (8:52.29); in the Junior group, Elliot Bunney won the 100 and 200 metres (10.48 and 22.13), Brian Scally the 1500 (4:04.5), Tom Hanlon the steeplechase (5:54.54 – record) and Mel Fowler the long and triple jump double (7.01m and 14.20m). At Milngavie Highland Games, Andy Daly broke his own course record for the road race with David McMeekin in second. The Scottish Men’s League match was won by Edinburgh AC from Edinburgh Southern – both clubs dominated the league scene through most of the 80’s with Edinburgh AC having two teams in the five division league.

Many of the same names were visible in the Scottish Schools Championships at Crown Point. Take a look at the results for the17-19 years age group.

| Event | Winner | School | Time | Comments |

| 100m | E Bunney | Bathgate Academy | 10.5* | equals CBP |

| 200m | E Bunney | “ | 21.3 | new CBP |

| 400m | M McPhail | Mainholm Academy | 49.7 | |

| 800m | T Hanlon | St Augustine’s, Edinburgh | 1:56.3 | |

| 1500m | S Wallace | Cathkin HS | 3:59.4 | |

| 5000m | M Wallace | St Thomas Aquinas | 15:53.3 | |

| 110h | A Thain | Douglas Academy | 14.8 | 14.7 Heat: CBP |

| 400h | R Bradley | Chryston HS | 56.5 | new CBP |

| 2000 steeplechase | S Allan | St Aidan’s HS | 6:22.6 | |

| high jump | E Leighton | Inverness Royal Academy | 1.95m | |

| pole vault | C Knox | Edinburgh Academy | 3.70m | |

| long jump | A Thain | Douglas Academy | 6.90m | |

| triple jump | T Wright | St Augustine’s, Glasgow | 13.63m | |

| shot putt | D Miller | Merchiston Castle | 12.61m | |

| discus throw | R Devine | Golspie HS | 45.04m | CBP |

| hammer throw | R Devine | “ | 52.98m | CBP |

| javelin | G Swann | Glenalmond | 53.98m |

Quite impressive, I think. The Girls championships were also being held on that Saturday at Pitreavie. Mary Anderson was far and away the top athlete here – two throws victories and a third in the 400m could have been three throws gold medals but for the fact that the rules only allowed her to compete in two throwing events. She added a metre to the shot record with 13.65m and more than three metres to the javelin record with 46 metres exactly. Her time for third place was 59.1seconds. Apart from her performances, the Herald report commented that the standard was ‘worryingly low’ at these championships.

Under the heading ‘Sharp Is Fastest In Britain’, there was a report on both men’s and women’s GB Cup competitions at Grangemouth on Sunday. Cameron Sharp won the 100m in 10.5 and the 200m in 21.0 which was the fastest in Britain up to that point in 1985. Meanwhile, Carol Sharp won the women’s 1500m in 4:30.1. Mary Anderson won the shot (14.41 pb), discus (39.80) and javelin (46.62m pb). Jim Brown was almost as active as Mary Anderson in that he competed on both Saturday and Sunday, and won both events – Hamilton Sports 6 mile road race in 29:23 and the Bo’ness 9 mile road race in 44:16 which was a minute better than Terry Mitchell’s record for the course. He was only 4 seconds ahead of Douglas Bain (Falkirk VH) who was also inside the old record.

In the Scottish championships at Meadowbank on 22nd June, Lynsey McDonald, who had really set the heather on fire with her performances at Moscow in 1980 only to succumb to illness and injury thereafter, showed that she was back in form when she ran won the 400m in 53.33 seconds from lane eight. Inside the qualifying standard for the world student games in Japan it was a heartening sight for the spectators and selectors. Others from 1970 to compete were Chris Haskett Price who won as an intermediate in 1969 won the inaugural women’s national 10,000, and Moira Walls who finished fifth in the high jump behind Jayne Barnetson’s 1.83m championship record. The men’s 400m was a race to watch – won by Brian Whittle in a record 46.6 with Mark McMahon on 47.4, one tenth ahead of Martin Johnston. Elliott Bunney won the 100m in 10.63 into a headwind of 1.19m a second, and became the first man to win Scottish schools, Scottish Junior and Scottish senior in three successive weeks. Paul Forbes trailed newcomer Tom McKean through the first 400m of the 800 in 59.18, waited for his chance and was out kicked at the end. The 1500 was almost a reply with the 1984 champion John Robson being out kicked by Alistair Currie, the 1984 top GB junior at 1500m and 3000m in a 55.4 second last lap. Ann Purvis beat Carol Sharp in the 800m in 2:05.75 and in the men’s 5000m, George Braidwood (14:01.17) defeated Robert Quinn (14:03.70 and Alex Gilmour (14:06.53) while in the marathon, Evan Cameron won in 2:22:40 from Colin Youngson (2:23:) and Graham Getty (2:24:13). It was Youngson’s 10th championship marathon medal.

Tom McKean was the man who really came to the fore in 1985 as the article by Doug Gillon on the international meeting in Gateshead on 29th Jun indicated. “The speed with which Tom McKean fulfilled a prophecy was almost as devastating as the burst of pace with which he cut down Steve Cram to win the 800 metres for Britain at Gateshead on Saturday. UK Director of Coaching Frank Dick last week predicted a long and distinguished career for McKean who won his first full UK vest in the international against France and Czechoslovakia. But even Dick was surprised – almost as stunned as Cram and his partisan Geordie support – as Lanatkshire labourer McKean dug in after a 54 second opening lap to overhaul the world 1500m champion and Olympic silver medallist. The Clyde Valley Scot clocked 1:47.25, a lifetime best, with Cram three yards adrift in 1:47.61. “Tom is now ready to take on the very best,” said Dick afterwards.

Cram, albeit tired after a flight from Oslo where he had set the third fastest 1500m time in history, had hit the front with 350 metres to go. But McKean, the UK and Scottish 800m champion who is unbeaten over two laps in two years, remorselessly pursued the blond Geordie and outlasted him in the straight. “I didn’t feel too tired and reckon I can go a lot faster given the right sort of race, said McKean, who with Zola Budd were named the athletes of the meeting. Cram, a full time athlete who can command vast advertising fees and boasts a trust fund which now must be nearing six figures, is a stark contrast to McKean a £60 a week labourer with Motherwell District Council.

The 21 year old McKean could not afford to enter last year’s UK championships at Cwmbran and his first representative trip last month was only because of the UK title which he won in Antrim. He got a trip to Madrid where he set a personal best of 1:47.6 which he has now lowered again. Cram – who says he will need an operation later this year to resolve compartment syndrome which causes agonizing muscle pain – was not the only superstar to be eclipsed. Steve Ovett was outshone and outsprinted by former Scottish 800m champion Chris McGeorge over 1500m. “ McGeorge’s time was 3:50.50. Cameron Sharp, appearing as a guest in the 100m, ran 10.51 behind winner Linford Christie’s 10.42, And in lane one of the 200m he clocked 21.03, his fastest electronic timing since 1983.

Meanwhile in the international against Ireland and Catalonia in Dublin, Alistair Currie was second in the 1500m in 3:44.64, Brian Whittle won the 400m from Martin Johnston in 47.16, Paul Forbes and Stuart Paton were another 1-2 for Scotland (Paton won) in the 800m with 1:50.77 and Geoff Parsons won the high jump with 2.15m. Edinburgh Southern Harriers finished seventh in the final British League match at Meadowbank wand were relegated to Division Two. In the Division Two match in Leeds, Edinburgh AC could only finish fourth (nine of their top men were competing for Scotland in Dublin on match day) and failed to gain promotion. McLaren Glasgow was a close third in their British League Divison Two match at Cosford.

Road racing was still going on apace and the Buckie Round Table Half Marathon Charlie McIntyre of Banff Coasters won in 77:27 from Don Ritchie who the previous week had set a British best for 100 kilometres and this week ran 79:44 to be first vet as well as runner-up. In the Lairig Ghru race, John Lamont of Aberdeen beat Dave Francis of Fife AC.

It was a very busy weekend with the trend towards bigger meetings outwith Scotland filling the headlines and domestic racing being down the column a bit. The trend was noticeable throughout the 80’s but on this week end it was more noticeable than most – only one track meet (the Division One League Match at Meadowbank) in Scotland, a road race and a race through one of Scotland’s most daunting hill passes.

July started with GB international Birmingham against East Germany and Tom McKean with some help in the form of advice about Wagenknecht the German, from Steve Ovett won the 800m in 1:47.11. At home David McNeill of Lochaber won the Mamore Hill Race and John Mudie of Shettleston won the Riding of the Marches Half Marathon at Annan in 69:56. Lawrie Spence won the 10000m road race and smashed his own record by 42 seconds when defeating Tommy Murray at West Kilbride.. At Carluke Highland Games, Ayr Seaforth won the SAAA 4 x 400m relay championship and Peter Carton won the 10 mile road race in 51:31, beating Charlie McDougall by 250 yards.

The SWAAA Junior championships at Grangemouth contested the headlines with the Scottish Veterans championships at Coatbridge on 13th July. Mary Anderson, competing in the new Euro-Junior age group took the bigger print with her victories in shot (14.40m) and javelin (45.90) and second place in the discus (40.80m) – but when the trophies were to be presented, it was found that she had left the stadium! Gail McDonald (McLaren Glasgow) won the 1500m by 13 seconds in 4:32.8 but had to be content with second in the 800m behind Linda Purdie (EAC) who won in 2:13. Jayne Barnetson won both high jump (1.80m) and long jump (5.56m) In the vets championship it was an Australian, Frank Turner, who won the 100m, 200m and 400m 11.7, 23.6 and 52.6 seconds. Dick Hodelet had a very good double in the 800m and 5000m winning both but slipping to second in the intermediate distance 1500m. But the marathon scene being in full swing, the Caithness Marathon was also taking place on the Saturday and was won by Robin Thomas in 2:36 leading Hunters Bog Trotters to team victory with Dave Tayler and John McKay fourth and fifth. Pamela Vorverk of Lochaber won the women’s race. At the other end of the country, David Cavers won the Duns Law Hill Race by 150 yards from Graham Haddow of East Kilbride.

On Saturday 22nd July Scotland was competing in an international fixture against Wales, Catalonia and an English select at Cwmbran under the captainship of non-competing Allan Wells. Gus McCuaig won the 100m however in 10.7 in a competition in which Scotland was second to England. Other Scottish winners were Brian Whittle in the 400m in 47.5 seconds , Tom McKean in the 800m in 1:51.62, Ross Copestake in the 3000m in 8:12.3, Liz Lynch won the women’s 3000m in 9:13.4, women’s 100m hurdles Pat Rollo in 13.7 and Jayne Barnetson in the high jump in 1.82m. Incidentally this victory by Tom McKean extended his winning streak to 34 successive races. Meanwhile in the British veterans championships at Wolverhampton was winning two gold medals and one silver – the first places were in the 100m (13.3) and 400m (60.3) with the second being in the 200 (28.2). He had just turned 60 on the Friday. It was a busy weekend with the SWAAA pentathlon, the Inverness 10000m, the Irvine half marathon and the Irvine Triathlon also taking place.

At Inverness in the Turnbull Sports sponsored 10Kroad race, Simon Axon won from a field of 650 from Alan Wilson of Victoria Park in 30:11. Lynda Bain of Aberdeen won the women’s race and set a new best time for the distance of 33:27 when finishing thirteenth overall. At Irvine, the leaders got lost and ran, it is estimated about 15 miles before Ray Curley and Robert Boreland won in 84 minutes. In the pentathlon, Anglo Scot Valerie Walsh was third and Moira McBeath fourth. There was also a preview of the match on Tuesday 23rd at the Dairy Crest Games in London. There were several Scots at the meeting and all performed well. Nat Muir won the 3000m in 7:51.46 with Colin Hume third in 7:53.06, Yvonne Murray was third in the Mile in 4:28.46, and Lynsey McDonald was third in the 400m in 53.79. Tom McKean was in unusual territory when he raced the 1000m, won by Steve Cram (2:15.09), where he finished sixth in 2:18.91. In the Sprinter competitions, Elliott Bunney won the Junior race in 10:59 and Cameron Sharp was third in the senior 100m in 10.46.

Yvonne Murray was racing at Bislett on the last Saturday of the month and despite suffering mid-race stomach cramps set a new Scottish national and native record for 10000m track of 33:43.8; Lynsey McDonald raced in the 400m and was timed at 53.65 to win and record another time inside the qualifying mark for the World Student Games. At the TSB Women’s Championships in Birmingham, Ann Purvis was second in the 800m to 2:02.41. At Balgownie, Robert Cameron outsprinted Steve Doig in the 3000m to win in 8:28.1 to Doig’s 8:30.6 and Elspeth Turner won the women’s 1500m in 4:33.7. In the League Match held in Glasgow, Cameron Sharp ran a swift 200m in 21.17 to win the 200m: he had already run faster but it enhanced his chances of being selected for the Europa Cup match in August. In the Division Two contest the top athlete on display was George Braidwood of Bellahouston who won the 1500m in 3:50.28 and the 5000m in 14:37.71. Billy Bland won the Ben Nevis Race from Peter Hall.

Unfortunately there were no Rangers Sports on the first Saturday of July, but there was the Strathallan Gathering in Bridge of Allan where Springburn’s Graham Crawford won the 1500m handicap and Jim Cooper won the 3000m handicap while Derek Easton won the 14 mile road race. In Edinburgh, Mike Carrol won a hard fought race with Jim Brown (Clyde Valley) and Lindsay Robertson (EAC) to take the TSB 10 mile road race in 49:46. Elliott Bunney retained the British junior 100m title in 10.39 seconds. There had been five false starts before Bunney had the chance to win. There was an international meeting in Budapest in which Cameron Sharp was seventh in the 200m in 20.95 seconds and Tom McKean was second in the 800m in 1:46.05. At home, Alan Farningham won the Creag Dhu Hill Race at Newtonmore, Ann Curtis won the women’s race and Mel Edwards was first veteran. Geoff Capes broke three ground records at Aboyne Highland Games – the games circuit has an attraction for English ‘heavies’ beyond the money aspect – John Savidge in the 50’s, Arthur Rowe in the 70’s and Geoff Capes in the 80’s were among the top international throws experts to try their hand in the Highlands. Jayne Bartnetson enhanced her chance of selection for the Junior Europa Cup when she set a new high jump record in the inter-area match at Middlesborough, as did Mary Anderson with a 14.83m shot putt, despite having three no-throws in the discus. On the track, Yvonne Murray won the 1500 with Karen Hutcheson winning the B race, and there was a Scots 1-2 in the 3000m where Elise Lyon won from Gail McDonald. And Sandra Whittaker made a come-back after injury with a 12.4 100 metres in the GRE Cup match.

On 17th August Jim Brown won the Monklands Half Marathon in in 69:16, Sam Graves won the Ceres half-marathon in 76:01 and M Lindsay (Carnethy) won the Dalchully Hill Race at Laggan Bridge, but the big headlines were for the Europa Cup. Here Tom McKean won the 800m in 1:49.11, and Nat Muir was in hot water with the selectors after not running in the 3000m. On Thursday his car broke down and he missed the shuttle to London and missed the connection to Aeroflot; then when he did get on to a plane, it went to the end of the runway and turned back because of engine trouble. Trouble with the tickets led to him phoning the BAAB who sent him a new ticket but then a personal problem arose and he couldn’t fly out. There was talk of him being black-listed by the Board and never selected again but luckily that didn’t transpire. The last home countries international at Meadowbank was held after sponsors Arthur Bell withdrew their support. There had been some good performances there – Mary Anderson and Mitchell Smith won the women’s and men’s shot putt events, Jayne Barnetson won the high jump and Pat Clarke won the women’s 400m with 55.61 seconds.

With international fixtures or major track meets in England every weekend, the Scottish track and field scene was vastly different from the 70’s never mind the 60’s and the 50’s could have been on a different planet such were the conditions and athletes. Was the scene any better at developing young athletes might be an interesting question to debate.

The top story on Monday 26th August was that Glasgow AC had won promotion to the first division of the GB women’s league. The sponsorship received from the McLaren Group enabled them to fly Angela Bridgman back from Los Angeles at a cost of £3000 to compete. They reckon that she repaid this by winning the B 200m in 25.02 seconds and finishing fourth in the 400m before flying back to the USA. Sandra Whittaker possibly made her own way from East Kilbride to be first in the 100m (11.9) and 200m )23.8). 17 year old Gail McDonald won the 1500m and Elspeth Turner (after winning the Crieff Road Race the previous day) was second in the 800m and third in the 3000m. Carol Sharp won the 800m in 2:08.6. In Cologne Tom McKean won the 800m beating Barbosa (Cuba) and Ed Koech (Kenya) in 1:47.13 – but that was in the B race – breaking into the top tier against so many vested interests was not easy. He was of course sponsored by Glen Henderson – everybody had a sponsor of some sort. In the European Junior Championships at Cottbus, Germany, Elliott Bunney won the 100m and was part of the winning 4 x 100m relay team. Tom Hanlon was fourth in the final of the 2000m steeplechase5:39.3.

Back in Scotland, Cavan Woodward (Leamington) won the Two Bridges Road Race in 3:40:40, Graham Crawford on the Town and Country 10 miles from Crief town centre in 53:59 to defeat Frank Harper by 80 seconds and John Duffy won the Inverclyde Marathon in 2:32:44.