Joe McGhee was Scottish Marathon Champion three times; he ran in the international cross country championships three times and had many fine races on the road and over the country but will be most remembered for a race that he won in controversial circumstances – the 1954 Commonwealth Games in Vancouver when Jim Peters totally misread the conditions and collapsed before the finish after a dramatic struggle round the final lap of the track. McGhee ran in a few minutes later to win the gold but the Press almost universally homed in on the drama surrounding Jim Peters which had been captured on film and shown in cinemas round the world. It caused a tremendous furore in Scotland and there was correspondence in every daily newspaper. The correspondence was nowhere more explicit than in the ‘Scots Athlete magazine and I enclose some of it below – including a two page letter from Jim Peters and an excellent article on the role of the Press by John Emmett Farrell. It is immediately below and his career at home will be dealt with on a separate page altogether in the Marathon Stars section. After the report on the race in “Scottish Athletics”, the official history of the SAAA, by JW Keddie, the first article is by George Barber and was the first article to appear in the SA on the topic – a full month before the following pieces. The page then has some extracts from the SMC Minute Book and comments on a wee exchange with the SAAA. And at the bottom is a look back with extracts from an article in ‘Scotland’s Runner’ in 1987 to give some Scottish historical perspective to the events. And finally comes the version that Joe himself gave to ‘Scotland on Sunday’ in August 1994 as supplied by Colin Youngson.

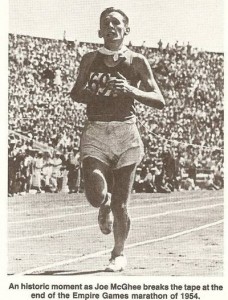

August 7th, 1954 was noted for two main athletic events at Vancouver – the so-called “Mile of the Century” involving Roger Bannister (Eng) and John Landy (Aus) and the marathon involving the great Jim Peters. Sixteen runners lined up at the start of the race in which Joe McGhee was the only Scot. He ran a canny race in excessive heat. Early on he tried to stay with Peters and compatriot Stan Cox but was forced to drop back. In the conditions Cox too found the going hot and dropped back at 15 miles by which time Peters was literally miles ahead setting his usual relentless pace. This however was his undoing for as he entered the Stadium about two and a half miles ahead of McGhee he was suddenly overtaken with exhaustion and staggered and lurched round the track, now one way now another, in pathetic fashion until he was pulled out a furlong from the finishing line. Meanwhile back in second place, as he thought, McGhee had fought off a challenge from the South Africans Jackie Mekler and Johannes Barnard. It was a full quarter of an hour after Peters first entered the Stadium that the little Scot came trotting on to the track to a great cheer. His victory in 2:39:36 in such difficult conditions deserves more acknowledgement than it has ever received. What is more, there is no truth in the tale that he was on the verge of giving up or indeed that he was waiting for an ambulance to pick him up when he was advised of Peters’ demise and decided to carryon. In the end he simply ran the most sensible race on the day.

From ‘”Scottish Athletics.”

“That” Marathon Race

by GS BARBER

Having had some 48 years experience of dealing with marathon runners may I join with those youthful reporters in the discussion on their ‘This MUST not happen again’ race. This WILL happen again so long as there are men like Jim Peters who will put out every ounce of strength to win races whether it is a marathon race or 100 yards. I have seen men far more exhausted in a 440 yards race than in marathon races, but the reason that there is an outcry about this one is that it was a major event attended by big newspaper men. My experience of marathon running is that it has always been a sort of ‘unwanted baby’. Look how long it took to convince the AAA that a marathon championship was an important event, it took even longer to convince the Scottish officials to consider this.

When a race of this kind is proposed promoters usually find an empty space in their programme to allow the favoured few to finish on the track but they usually continue the other events as if the marathon race was not in being. How many times have we seen the road race from Drymen to Firhill Park messed up at the finish with officials NOT connected with the race directing men the wrong way round the track or holding up a tape at the wrong finishing place. I saw an unholy mess at the White City, London, at the finish of the British marathon championship. (The leading officials of the race came into the ground at least fifteen minutes before the leaders were due to arrive, I know because I was with them) warning those in authority that the race was approaching. Did it make any difference? Not a bit, they started a hurdle race on the track and when the runners entered no one knew what to do and the two men Squire Yarrow and Donald Robertson running together dodged and ducked in and out of the hurdles until they were dizzy. The result was that Donald Robertson was beaten by a short head in a most indescribable mix-up.

I must admit that a man at the end of 26 miles is not so bright as he was when he started, more reason that everything should – and could – be made easy for him to finish the race. The finishing point of this race is usually in a different place from that of other events and the officials for the marathon race should explain to each competitor how he enters the track, the number of laps to go and the finishing point. But when something untoward occurs all sorts of men take on the role of advisers and upset the race. It was reported in the newspapers ………………….that Mick Mays the team masseur who helped Peters on the track said “I caught him at what WE THOUGHT to be the finishing line before he had a chance to fall. Note these words ‘at what we thought to be the finishing line.’ I saw what happened at Vancouver in two news-reels pictures. When Peters saw an official standing in the middle of the track I am sure that he thought the white line was his goal – and just stopped. In fact he could not have run on because the person stopped him and caught him.

Jim Peters must take much of the blame himself. He has been running long enough to know to make full allowance for the conditions. The fact that he was so far ahead shows that it was an unnecessary folly to run himself out. Lets be sensible about this race. Peters can run again and forget about his unlucky break. Dorando Pietri ran some of the best races of his career after his dramatic collapse in the marathon race at the London Olympic Games in 1908 and I remember some of the papers said the same things.

How many of us have gasped at the end of a marathon race and said ‘never again, this is my last race and after a bath, rest and some food are looking for entry forms for the next race. But remember – in the future when we discuss this race let us not forget (as some would have us forget) who won the race – Joe McGhee. Because almost everyone knows that Dorando Pietri collapsed at the finish of the 1908 Olympic Games but very few know who won the race. It was JJ Hayes of America, time 2 hrs 55 mins 18 secs, and the first Britisher to finish was WT Clark, Liverpool – who was 12th.

————————————————-

Now we have the official version of the event dealing with the English complaint that the course was too long and that they were denied access to their athletes during the race.

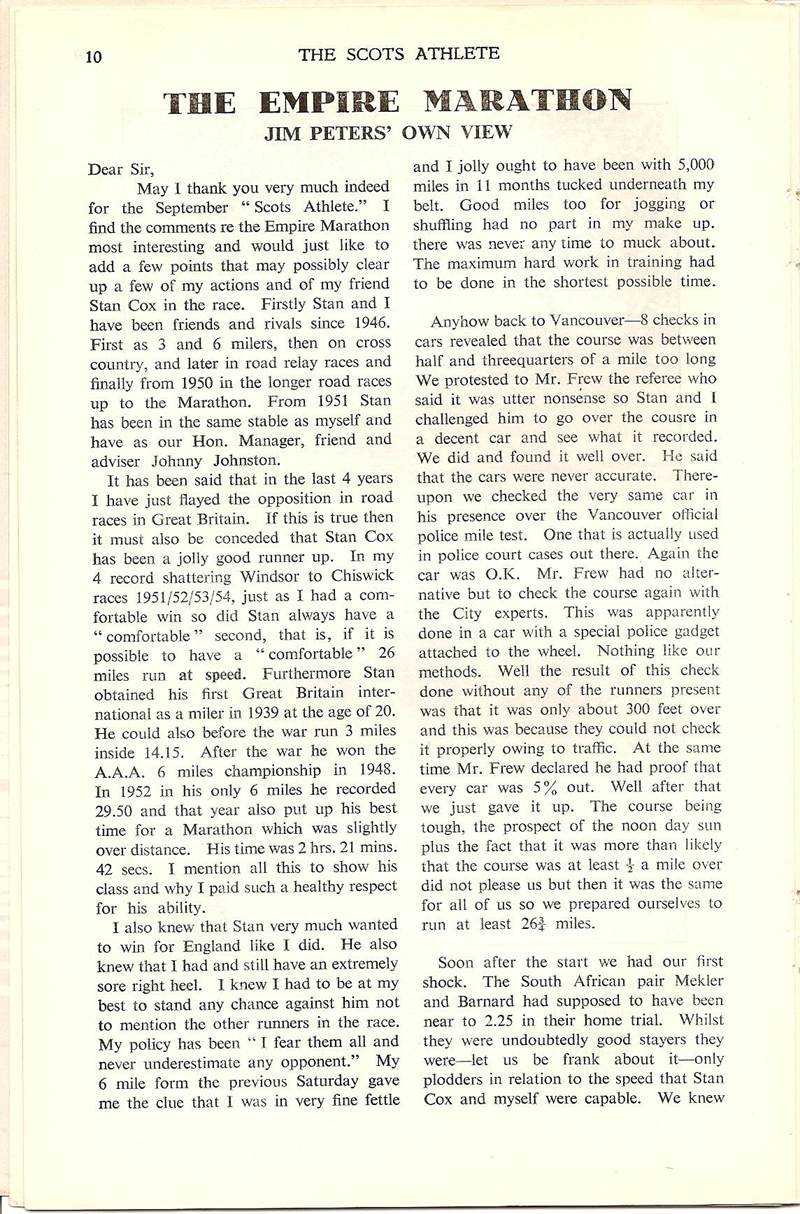

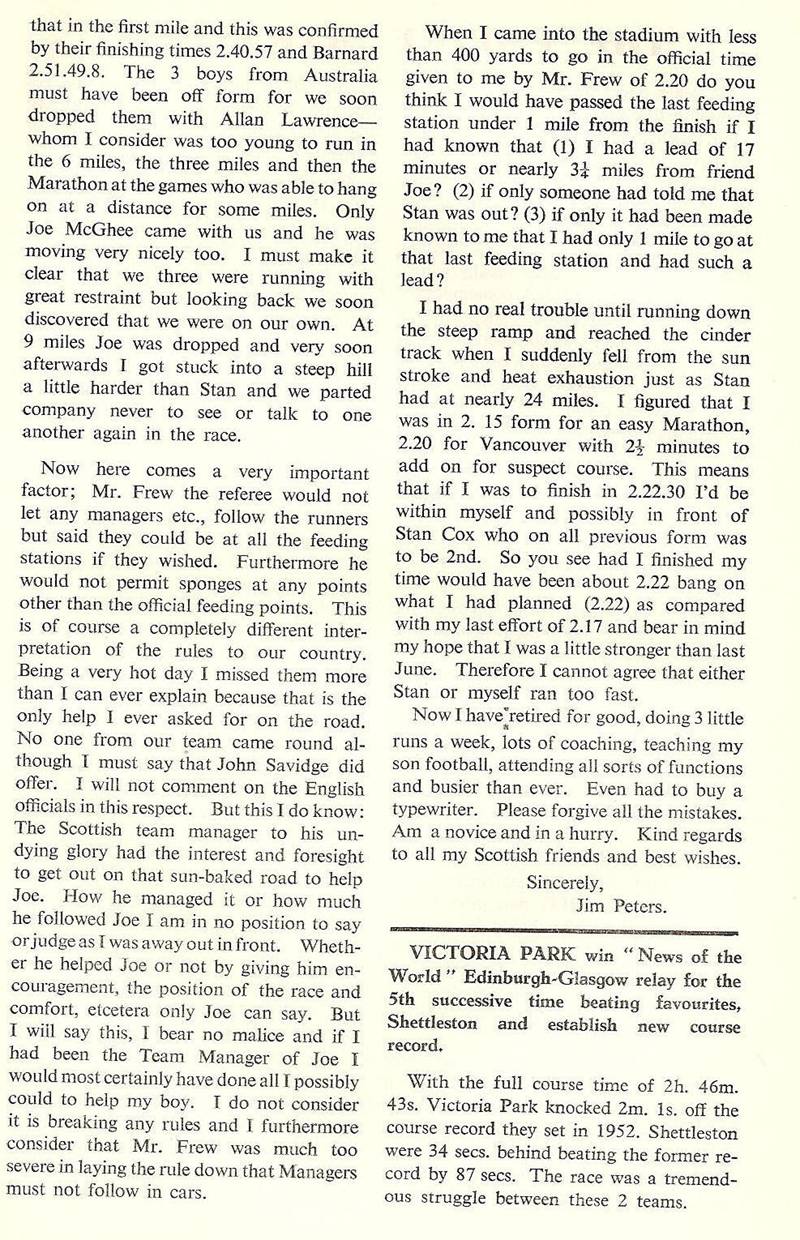

THE EMPIRE MARATHON

On other pages we have been pleased to publish Jim Peters’ letter. It is a sincere letter which speaks for itself and on which we have no desire to comment. However in view of Jim’s references to the distance and measurement of the Empire Games marathon route and because moreover of an article by Maxwell Stiles headed ‘Did Jim Peters really win?’ which appeared in our USA contemporary “Track and Field News” supporting a claim that the race was considerably over distance and on the question of re-measurement attacks “stubborn Vancouver officials” we feel it is only just and proper to present the views of the marathon organiser Mr Alex Frew. These appeared in a full article in the ‘Vancouver Sun’ for 12th August. We are reproducing here only the necessary extracts.

The introduction to the article, reprinted here, gives the explanation to Mr Frew’s account. “Storm of protest stirred up over the tragic Jim Peters case in the British Empire Games marathon last Saturday hasn’t subsided. Questions have been asked and accusations hurled regarding the pitiful marathon ending. In an attempt to shed more light on the case Vancouver Sun staff reporter Al Fotheringham interviewed Alex Frew chairman of the marathon committee . Here is Mr Frew’s story. ‘There has been so much discussion and so many inaccurate statements about Saturday’s BEG marathon race I think the public should be told the true facts of the case once and for all. I was in charge of the marathon as chairman of the marathon committee and and referee and in charge of the actual running of the race. The whole thing took two or three months of laborious preparation so if anyone should know anything of the marathon, I should. Everything about the marathon was scientifically prepared and checked. It was probably the most difficult event to stage in the whole BEG. Thanks to the co-operation of the city police and the RCMP the actual running of the race came off perfectly. The course was measured five times after the English team protested that it was too long. I might point out that the Australian team which had been here ten days before the English had been over the course thoroughly and were satisfied with its length until the English protested. The first time it was measured under the supervision of Professor JF Muir head of the UBC Civil Engineering department. Also present was the city Traffic Inspector Jack Harrison who arranged for control of traffic while the course was being measured.

CUT 250 FEET OFF COURSE

After the English protest the course was re-measured on August 4th by a foot-o-meter reading. Because traffic control could not be arranged on such short notice we were not able to cut the corners as a runner would and we found the course 250 feet out. We cut 250 feet off the course – 250 feet off 26 miles 385 yards. The English measured the course by a car speedometer and I have a certificate saying that no speedometer reading can possibly be accurate. Every preparation for the race was properly carried out. There was six feeding stations along the course, one at ten miles and one every three miles after that. Every station was manned by an average of six officials so that runners would not have to stop. The exact requirements of every runner were supplied at every station. For example the list shows that Jim Peters required ‘A glass of water; a sponge dipped in water not wrung out’ . For a South African runner the list reads ‘One apple, a glass of cold sweetened tea. Other runners were given exactly what they wanted.

“Two medical cars followed the runners to pick up stragglers. Other radio equipped official cars were ready to rush aid to any runner who was in trouble. It has been stated in the English press that English officials were not permitted on the course. This is not true. They were told they would not be allowed to accompany the runners in a car. I wanted as few cars as possible on the course for the simple reason that I wanted to keep exhaust fumes away from the runners. English officials and all other officials were told that they could station themselves at the feeding stations to keep an eye on their runners. The English did not take advantage of this opportunity which was open to all. I personally saw Scotland’s coaches at five different spots around the course. There were 103 officials around the course and 40 policemen.

All runners received a map of the course showing the route outside the stadium, also a gradient map showed the grades of the hills. All runners were shown at the start of the race the exact finish line.”

————————————————————————-

There you have it from the officials involved. Jim Peters had his own version of the race and the magazine printed it over the best part of two pages and it is here in full.

___________________________________________

But it was not only Joe who got short changed in the media – Jim Peters became the butt of many a cruel joke – when I first saw the film in the cinema newsreel, there was a lot of laughter from the audience who at first didn’t realise what was going on. There may have been some understanding of their reaction because it was unprepared for but there was none for the sports writers of whom the celebrated Peter Wilson wrote for the ‘Daily Mirror’ which was the most down market of the Press in the pre-Sun days. Many took exception to the coverage and Emmett Farrell felt obliged to record his feelings in no uncertain fashion showing that pride in Joe’s achievement did not mean taking pleasure in Jim Peters’ misfortune.

PETER WILSON ASHAMED

By John E Farrell

Describing Jim Peters’ collapse at the end of the Vancouver marathon in the Daily Mirror Peter Wilson says “I felt Dirty and Ashamed” After reading his article I am not surprised. I too felt ashamed on his behalf. Admittedly Jim Peters’ collapse in the stadium at the end of a gruelling race was unfortunate. Agreed too that a person has the right to express his own opinion. But surely that statement should be balanced and objective and not lacking in dignity.

For the benefit of readers who were fortunate enough not to read the article let me quote some excerpts from his text. Describing Peter’s entrance, Wilson writes – “But he is not a figure of merry jest; he is a refugee from an insane asylum, a fugitive from a padded cell” …”He is Jim Peters ‘Mr Marathon’ himself but he is a frightening caricature of the man I have called Jim hundreds of times…two steps forward, then three to the side, so help me he’s running backwards now ….There is more to follow – much more. This poor dumb man who only wants to win for England … but this isn’t the fight game. This is nice clean amateur sport – and game Jim does get up. Mark you, he’s not in very good shape now. In fact he looks pretty shop soiled – this item marked down.” and now for Wilson’s peroration. “… So Jim Peters – what does he remind you of, a landed fish with a gaffed jaw heaving for water and dying in the sun, a trapped and bloody fox which has gnawed his own leg off for freedom, a rabbit with infected myxomatosis beating its own brains out?”

After that description I thought Peters looked uncommonly healthy when he appeared on TV some days afterwards. It didn’t seem right that he should appear in such good shape. Yes, Peter Wilson calls Peters ‘Jim’. But because a man calls you by your first name he is not necessarily your friend. On the basis of that article Peter Wilson is no friend of Jim Peters, no friend of athletics, no friend of that fine instrument the English language, no friend of journalism and perhaps in the long run no friend even of the newspaper which he represents. Athletics needs and desires advertisement. But not the kind that comes from the sensation-monger lurking in the shadows. Why does not Peter Wilson confine himself to the prize ring where despite his frequent horrifying and harrowing experiences he seems more at home? Unless he can do better, he would be doing a service to athletics by leaving it severely alone.

So there you have it! Whatever the post mortems there was only one winner and Joe McGhee had the gold medal.

Maybe proudest of all the Scots were the members of the Marathon Club but there is a reflection of the times in the minor squabble with the SAAA after the victory. In the Minute of the Committee Meeting for August 1954 appears the following:

” Empire Games: The Committee formally expressed its great pleasure at Joe McGhee’s victory in the marathon race and the secretary reported having sent a cable in the club’s name within minutes of the news being known in this country. After some discussion it was moved by Mr Wilson, seconded by Mr Howie, that Joe be made an Honorary Life Member of the club. Mr Brooke moved, seconded by Mr Welsh, that he be presented with a plaque. These motions were carried unanimously. Members would be notified in a circular due shortly and would be asked to contribute towards the cost of the plaque, Messrs TS Cuthbert and John Wilkie to be approached regarding the plaque. “ It was also agreed that he be awarded the Robertson Trophy for the victory. The SAAA was notified about the decisions and then at the following meeting this appeared in the Minute: “[The letter from the SAAA] also pointed out that there was no objection to our presenting a plaque but SAAA permission should first have been sought. Exception was taken to this … and as none present were aware of a rule on this subject, after discussion it was moved by Mr Haughie, seconded by Mr Wilson that the SAAA Secretary be requested to clarify this matter.” In the Minute of the Meeting of 21st February 1955: “The reply indicated that there was no rule in the SAAA Handbook but it was an IAAF Rule Number 9 para 4 which governed the value of £12 as souvenirs or prizes. prior permission was an additional safeguard for the athlete. Various members made observations and it was agreed to let the matter rest there.”

The plaque was important to the club partly because they had wanted to present the Robertson Trophy to Joe at the annual club presentation and social evening but SAAA had decreed that they would present the Trophy to the Vancouver Victor at their own function. In those circumstances the club would want to make some presentation to Joe who was a long standing SMC member and a former Committee Member. Nevertheless the whole thing is a bit different from today – eg Andrew Lemoncello’s profile on his blog has his occupation as “PROFESSIONAL RUNNER”

When Jim Peters died ‘The Independent’ newspaper had an obituary which carried the tale about Joe stopping five times and waiting for an ambulance when he heard that Peters and Cox were out of the race. It is important that the truth is told as often as possible and as clearly as possible and the following are extracts from an article in the ‘Scotlands Runner’ in 1987 by Jim Wilkie.

“Peters had performed poorly in the 1952 Olympics Marathon at Helsinki but was to make amends in the summer of 1953 when he clocked the first sub 2:20 time in the Polytechnic Harriers Windsor to Chiswick marathon (2:18:40). He came close to Gordon Pirie’s world record for six miles (29:07.4), won the British marathon at Cardiff and broke the course record for the Enschede marathon. When Peters then returned to Finland and gave her best runners a pasting, his fame spread to America and he was invited to compete in the Boston Marathon of 1954. The Finnish champion, Karvonen, however also got an invitation and promptly got his revenge in a punishing race which caused Peters to collapse at the end. Once recovered the Englishman began the summer of 1954 as he had that of ’53. In June he was once again victorious in the Poly and on August 7th he found himself on the other side of the world in Vancouver for the British Empire Games. Stan Cox and Joe McGhee were also lined up for this race and at three miles the three men comprised the leading group. At nine miles Peters made a move, and the fact that he appeared once again to be shaping up for a 2:20 time – despite the glaring heat – was astonishing to the race observers. Cox and McGhee could not keep up but the Scot was able to capture second place and fight off the challenge of the two South Africans Meckler and Barnard. As Peters approached the stadium he was two and a half miles ahead of McGhee. When negotiating the final hill however, for reasons probably associated with developing heatstroke, he began to wobble and upon reaching the track he fell – less than 400 yards from the tape. Memories of Dorando came flooding back and for that reason no one dared to assist him. Finally in the interests of Peters life, the English masseur Mick Mayes intervened and helped by shot putter John Savidge, he got the runner to a stretcher and then to the dressing room. Savidge and some of his team mates had previously been thumping the ground in encouragement and there was also the suggestion that Mayes had mistaken the finishing line. The next runner, McGhee, did not appear for almost twenty minutes but in holding himself together and effectively running a sensible race in very difficult conditions, he richly deserved his gold medal.”

**********************************************

And finally we have the REAL version – as written in the ‘Scotland on Sunday’ paper on 28th August 1994 and supplied to me by Colin Youngson. Joe’s own story – closely guarded for forty years – is below.

Joe McGhee’s Golden Triumph

(As printed in ‘Scotland on Sunday’ 28/8/94)

“The Marathon Race was timed to start at 12:30 – the hottest part of the day – and in the heat the sweat was dripping from us before we made a move. My tactics were simple. I had promised my Dad and Allan Scally, my coach, that I would run my own race and, no matter what happened, complete the course. I was competing after all against the fastest marathon runners in the world and, despite my own Scottish record, I was not reckoned among the top competitors in this race. Nevertheless I still had that little spark of ambition and privately determined to latch on to the leaders until I judged that their pace was too hot for me. I would then concentrate on finishing.

After a cautious cat and mouse start over the first mile, the race speeded up and the leading group of five – the Englishmen Jim Peters and Stan Cox, the Australians Kevin MacKay and Alan Lawrence and myself – broke away from the field. The crowds lining the closed off route round the city were most encouraging to us, but at times I seemed singled out for applause – so much so that Peters muttered a comment about the number of friends I had. I didn’t waste breath replying that it was the same Falkirk family, the Liddells, who by a judicious use of side roads kept re-appearing over those opening miles. I was surprised when the pint-sized but confident MacKay dropped back so readily at three miles, and then Lawrence at four miles. When five miles were passed in a modest time of over 27 minutes, Peters remarked that it was two minutes too slow. It was certainly fast enough for me! Yet he still held back. I was running quite comfortably and at seven miles was slightly ahead of the two Englishmen. Peter had given me some idea of his plans, however, and I was not surprised when between eight and nine miles he chose his psychological moment as we were about to tackle on of the notorious long hills on the course and suddenly launched himself into a tremendous spurt. In these conditions the pace was clearly suicidal for me and, resisting the challenge, I at once dropped back. Cox, however, plainly not in the least awed by Peters’ reputation, tried to hang on, determination writ large in every thrusting stride, but the race soon developed into a procession – Peters a white speck in the distance with Cox labouring vainly to prevent the gap widening. The heat was now becoming so unbearable that I couldn’t even bear the irritation of my long peaked baseball cap and threw it aside at ten miles.

For the next eight miles I ran completely alone with only the white vest of Cox in the far distance to aim at – Peters had soon disappeared from view – and I grew more and more uncomfortable as the heat began to take its toll. Then the clapping and cheering of the crowd warned me of the approach of another runner. Just before 18 miles, Lawrence, the Australian, passed me smoothly and confidently, and the gap opened astonishingly quickly. I couldn’t do a thing about it. This was the beginning of my personal crisis. Certainly, I felt bad, but the trouble was more psychological than physical. I simply could not visualise myself completing the eight miles still ahead. I plodded on and then with more than 19 miles gone, I saw a most cheering sight: Lawrence sitting disconsolately by the kerb. His encourahing remark spurred me on for only a short distance, however, and although I was back in bronze medal position I still could not see myself finishing.

Indeed, I ran through the 20 mile mark grimacing horribly at Willie Carmichael, the Scottish team manager. Remembering my promise to my Dad and to my coach, I was determined not to drop out, but I was hoping desperately that Willie would be merciful, take the decision for me and pull me out. His response was imply to scowl and gruffly urge me on. I swerved, half twisted to glare back at him, and found myself running into a high, jaggy hedge. The prickles and my resentment of Willie stung me into a short lived burst of speed. A mile or so later I was heartened once more by the news that Stan Cox was being taken away in an ambulance. Someone remarked that he had collapsed into a lamp post. Incredibly I was now in second place with less than five miles to go. It might just as well have been 50. My spasm of elation had evaporated, and the black pall of depression settled down again as I endured the next mile. Then at a road junction between 22 and 23 miles, I began to hear that ominous rhythmic clapping behind me: someone was obviously catching me up. I tripped on the kerb and the shock of the stumble jolted me into full awareness of the situation. I glanced back to see the two South Africans, Jackie Mekler and Johan Barnard barely 40 yards behind. Subconsciously I had been expecting them. Accustomed to ultra-long distances and to even hotter conditions and slow, canny starters, they had been reckoned the obvious threat in the closing stages if conditions had been tough – and they couldn’t have been tougher!

It was at that very moment my own personal miracle occurred, demonstrating the power of the mind over the body. I suddenly realised that I was going to finish these last three miles and, with that realisation, my energies and my racing instincts came surging back. Turning the next corner I plunged into the crowd of spectators at the edge of the pavement. The loud speaker vans kept blaring “Come into the middle of the road, Joe. It’s much clearer here.” But hidden by spectators I was not offering myself as a target to the following pair. At the top of this hill, I knew that the route turned left for a short distance, perhaps 50 yards, before abruptly swinging right again. Bursting from the crowd I spurted flat out to reach the further corner before my pursuers rounded the first. Then I settled down into a more comfortable racing pace. I did not dare risk a glance back over the the next two and a half mile in case I should offer the slightest encouragement to the South Africans. I was determined to fight every inch for that silver medal. the thought of gold never entered my head even when, near the stadium spectators began shouting that the man ahead was looking bad. Jim Peters deceptively awkward style with his head nodding forward always gave the impression of painful effort. My main concern was how I was going t tackle the last steep hill – a one in ten gradient – that led up past the stadium to almost roof level.

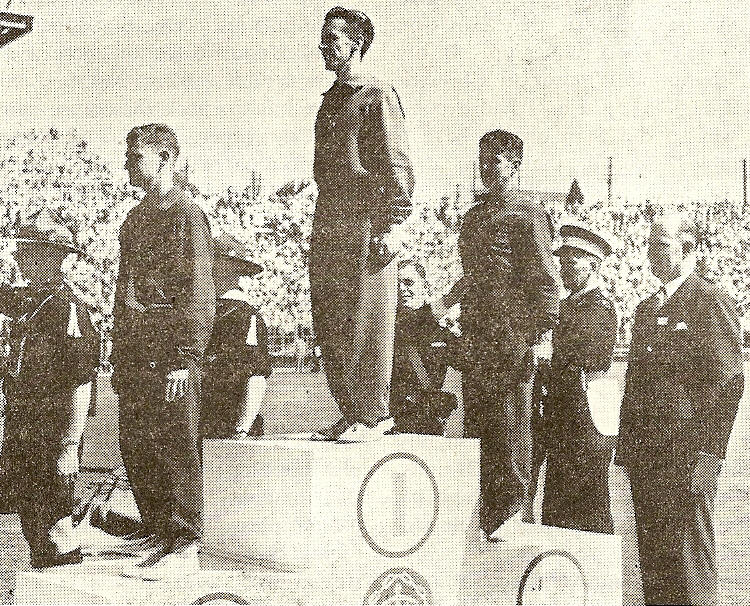

I had just reached the foot and was gathering myself for the effort when the news of Peters collapse was yelled at me. My first reaction was one of complete panic. How close were the South Africans behind me? I risked a glance back. As far as the eye could see, a good three hundred years or more, there was no runner in sight. I knew then that I could not be beaten and I never felt better in any race. The hill held no terrors for me now as I faced the climb. As I turned to run down the steep ramp past the stands into the stadium, I was struck by the deathly hush. The crowd had been shocked into silence by Peters’ colapse. “What is the next man going to be like?” was the question uppermost in everyone’s mind. They did not even know who was coming next, so little news of the marathon had percolated back to the stadium. There below me, framed in the opening to the track stood the track suited figure of Dr Euan Douglas, the Scottish team captain. I have never seen such a look of stupefaction on anyone’s face as realisation dawned and the big hammer thrower, dolphin-like, began to leap up and down waving his arms. I ran down into sheer pandemonium. I have never received such a reception. The crowd’s reaction must have been one of immense relief that this runner was not in a state of collapse. My ears were literally popping with the din as I raced around the track towards the tape to become at 25 the youngest marathon winner in the history of the Games.

The victory ceremony as the Scottish flag was raised will remain an unforgettable memory. It was also a fairy tale ending for the Scottish team to win our first athletics gold just as the Games were closing. I have been attempting to answer the question of what actually did happen in this historic race. I have only indirectly touched upon the question of why such a disaster occurred to Peters at all – and to Cox for that matter. England should have won the gold and silver medals comfortably, and it is not enough to point to the weather conditions and the hilly nature of the course to explain why they did not. After all these were the same for everyone and, when you race, you are competing not only against the other runners, but the elements and the course as well. You have to adapt accordingly. I personally ran half a minute slower per mile than I was capable of. Peters obviously did not. A world record time was simply out of the question that day. The whole point of the exercise surely was to win the medal and each of us was chosen by our respective countries to do just that. I managed to do so, Peters did not. A ‘glorious failure’ is all very well but it does not disguise the fact that Jim Peters, the best and most experienced marathon runner in the world at the time lost because he ran an unintelligent race.”

I Danced That Night till the Early Hours at the Closing Ball

ge in attempting to finish. The fact is obvious from the newsreel. Roger Bannister and I were the only athletes allowed to visit him in hospital, and I then realised how close he had come to dying. By contrast the newsreel also shows the strength of my own finish. It is when reports go on to tell what happened on the roads away from the stadium however that we move into the realms of imaginative fiction.

The essential point to remember about the Vancouver marathon is that it was taking place at the same time as the race between the two greatest milers, England’s Bannister who had broken the four minute barrier the year before, and Australian John Landy who had lowered the record after that. No one was going to miss the ‘Miracle Mile’ and consequently few reporters or team officials bothered to accompany the marathon runners. Besides the result wass considered a foregone conclusion: Peters, the fastest man in the world was the absolute favourite. To his eternal credit Willie Carmichael, the Scottish Team Manager, was a rare exception in following the race. Most reporters simply resorted to imagination in describing events out on the course. Unfortunately most of the myths that have grown up around the race to be embroidered in subsequent re-tellings, concern my part in it. They seem to have originated in the romantic fantasy of a local reporter who described how I was lying in a ditch until an old Scots lady revived me with the exhortation that the honour of Scotland was at stake. Norris McWhirter wrote a little later “Joe McGhee, an RAF officer, having fallen five times signalled for the ambulance. While waiting for it he heard that Peters and Cox were out of the race, so up got the bold Scot and finished the course to win.” The only true items in that statement are that I was an RAF officer and that I won.

The sad fact is that subsequent books and articles go on copying such second-hand, thrid-hand, fourth-hand flights of fancy. Even the AAA Centenary Handbook gets it wrong, as does Jim Peters in his own book. The ludicrous nature of such stories is obvious. Any athlete who has ever run a marathon will assure you that if you stop for even a second or two especially in the closing stages you will never get started again – even more so if you have decided to lie down. At no time did I ‘collapse’. I was engaged in a very active race pulling away from the two South Africans ove the last four miles and I never knew that I was first until just outside the stadium. Moreover because Peters and Cox ended in hospital it was assumed that I could not be much better. As for my state of so-called ‘exhaustion’ I need only point to the Press photographs of my sprinting through the tape both feet clear of the track, and then walking across the stadium afterwards with Willie Carmichael and Euan Douglas, and then the various pictures of the closing ceremony.

The most conclusive evidence of my fitness, however, was the fact that I danced that evening till the early hours at the closing ball, and was up again at 6 am for a trip to America. I suffered no after effects, and within a few weeks I was recording faster times than ever over the shorter distances, and the following season set a new native record of 2 hours 25 minutes 50 seconds in retaining my Scottish title. Incidentally, this time, the fastest for any Briton in the 1955 season, still failed to win me a British vest – but the treatment of Scottish athletes by the British selectors in this period is another

The 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games marathon in Vancouver has been labelled one of the 10 greatest races of all time. The awful collapse of England’s Jim Peters after he had entered the stadium is still recalled by the media with monotonous regularity. The fact that a Scottish runner won the race is sometimes also mentioned.ston and there is more information about Vancouver in a letter he sent to Frank Scally which you can read by clicking on the link.