After 20+ years of coaching, Iain retired from the sport and is now living in Kirkcaldy. He says retired – but he still acts as a consultant to other coaches and gives advice when he is asked for it. Coaches come from a variety of backgrounds – some are ex-athletes, some start as a parent who is dragged along by a child and ends up supervising then coaching, and some come from other sports. Iain is in the latter category.

He started after being a good standard amateur football player. He had been at school with Brian Scobie and they both played for the school team. Brian found his way into athletics but Iain was mainly a footballer. Like other young players of a good standard, there were times that he was playing three games at the weekend – for the school, for the scouts, for a local amateur team and so on. He joined the local Killermont Amateur Football Club for whom he played in most positions over the years. When the team coach moved away to another club, Iain started taking training sessions, and became a player coach. The high spot was probably when the team won the West of Scotland Amateur League Division One championship in 1963-64. He was interested in coaching but was coming into it as a player with no real knowledge of training other than from his own experiences.

In 1963 two Scottish football team managers, Jock Stein of Dunfermline and Willie Waddell of Kilmarnock, went to see how the great Helenio Herrera of Inter Milan went about training his squads. Ahead of their time, they would probably be ahead of their time were they to do so today. They came back and talked about what they had learned. Iain was interested in their findings. Herrera looked at training, saw how different players reacted to the same training, and understood them as individuals. Iain took on board the lessons about working with individuals as well as groups and teams and this affected how he worked with the football players he was training.

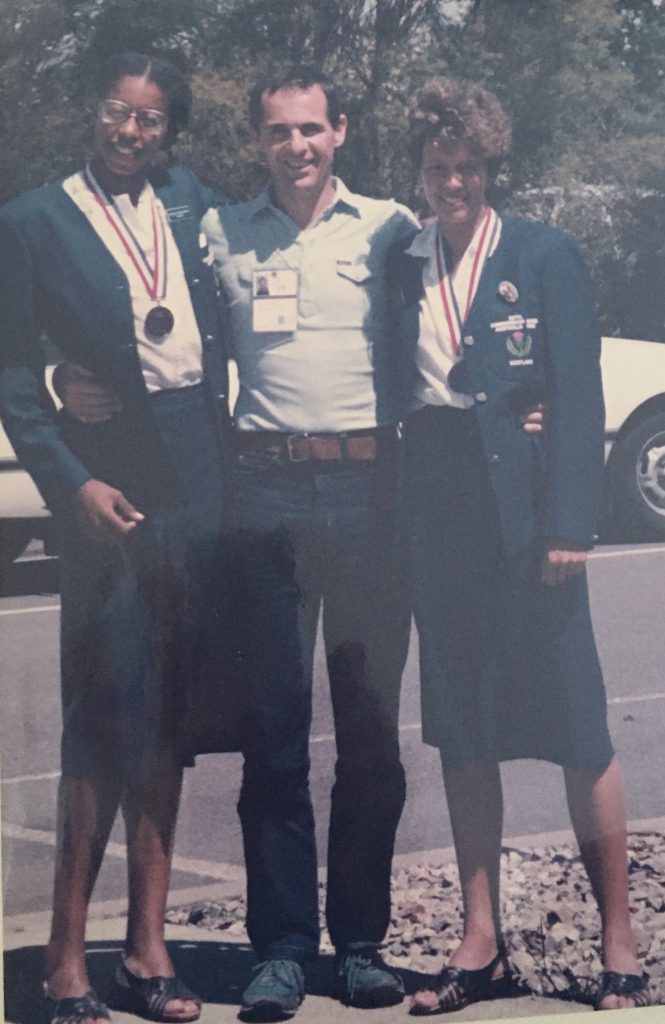

But he then wanted to take things a bit further and this led him into athletics. How did he get into athletics? He had friends participating in the sport, he had done some sprinting at school and he had also been friends at school with Brian Scobie who went on to do great things in athletics. So the contacts were there. At that time, with the publicity being given to the upcoming 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh with all the pre-Games hype, he decided to give up football and took up athletics. Friends encouraged him to join Maryhill Ladies AC where he met Jimmy Campbell and started out with a few athletes and started on the coaching ladder.

If we stay with the facts we see that his coaching career started like many others but then as his abilities and attitude were recognised, progressed further and maybe faster than most. At the time there were three grades of coach – Assistant Club Coach, Club Coach and Senior Coach. He came into coaching in 1970 and in 1974 he took his Senior Coach examination and qualified with the highest mark ever awarded by Great Britain Chief Coach Bill Marlow.

It was a rapid rise through the various stages. At that early point in his career he was already working with people in the club who were running in international fixtures. There were not many internationals at that time but through the mid 70’s he was asked by Frank Dick to go with some Scottish teams to small international fixtures in Norway and other countries. He was also working on the educational side of athletics with Frank and that also helped him to progress his coaching skills.

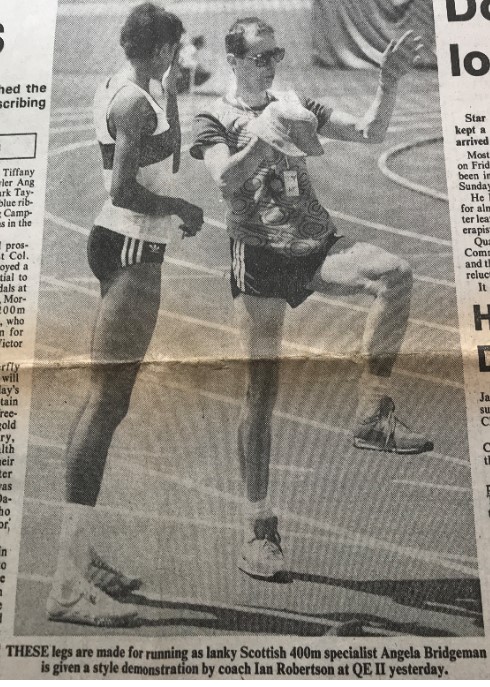

The Coaching structure in Scotland at the time was a simple but effective pyramid system with the National coach at the top and Group Coaches for the event groups (sprints, endurance, throws and jumps) below and answerable to him. Each group coach had Event Coaches for whom they were responsible. Iain became Group Coach for the Sprints in 1981 and Staff Coach for all sprint events. He held these posts until 1987. There was a considerable responsibility in both these posts.

His worth was quickly recognised and from 1982 – 84 he was the UK National Event Coach for both Men and Women 400m and the 4 x 400m relay. This was followed immediately by appointment as UK National Event Coach for Women’s 100m and 200m from 1984 to 1990. It had been a meteoric rise and was rewarded when at the National Coaches Conference in 1990 he was awarded the status of Master Coach.

With the GB Men’s and Women’s Sprint Squad: Iain is standing beside Linford Christie and in front of John Regis.

With the GB Men’s and Women’s Sprint Squad: Iain is standing beside Linford Christie and in front of John Regis.

Having looked at the outline of his career as a coach, we should maybe look at his philosophy of coaching and what made him so successful.

The coaching structure that he operated within, as outlined above, has changed irrevocably now but he has no doubts about its efficacy. In his opinion, one of its main virtues was that good coaches came together and worked together. They spoke to each other as coaches and learned from each other. They read about their events, they attended courses and conventions and brought the information back. It was a way of bringing all the knowledge together, assessing it and sharing it. Iain is adamant that you have to listen to people all the way through, you don’t have to agree with them but you have to listen to them and the structure was good at ensuring a two way flow of information.

The information exchange with everybody at all levels he sees as vital but who were the main influences on him? Undoubtedly some seeds were sown by what he read of Helenio Herrera (above) and his thoughts on the sports person as an individual. Given how early in Iain’s coaching career Herrera came along, we can have a quick look at what Wikipedia has to say about him. It says:

“Herrera pioneered the use of psychological motivating skills – his pep-talk phrases are still quoted today, e.g. “he who doesn’t give it all, gives nothing”, and “Class + Preparation + Intelligence + Athleticism = Championships”. These slogans were often plastered on billboards around the ground and chanted by players during training sessions.

He also enforced a strict discipline code, for the first time forbidding players to drink or smoke and controlling their diet – once at Inter he suspended a player after telling the press “we came to play in Rome” instead of “we came to win in Rome”.

It was about working with individuals – each individual reacts differently to the same training – and to do with motivation. If you look at some of the comments on this page you will see how much of a motivator Iain was when working with Glasgow AC some decades later.

When he joined up with Maryhill Ladies AC there was the influence of the livewire Jimmy Campbell – a wonderful coach with a lifetime of involvement in sport (football as well as athletics) and experience of working with athletes at all levels. As a mentor, Jimmy (on the right above) was in the very top class. A Scottish and British international coach he was always on the go, always keen to help other coaches – and always interested in the individual athlete or coach to whom he was talking or with whom he was working.

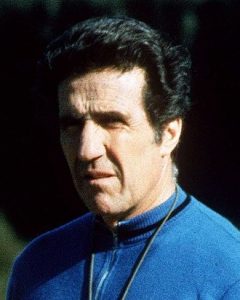

When Iain was working through in Edinburgh he travelled through to Glasgow three and four times a week – but he also did some work with George Sinclair and his athletes – another source of information and ideas. Add in Bill Walker at Meadowbank too. But from the mid 70’s he was influenced by National Coach Frank Dick (above) whom he thinks was outstanding at bringing to Scotland what was happening in the whole world of athletics. Iain found himself thrown into situations by Frank that challenged him and assisted him to develop even further. When one of his athletes (Val Smith) won the WAAA’s Junior 100m, Iain was invited to make a presentation at the International Coaches Convention presenting immediately after David Hemery – pretty daunting as a young coach, facing an audience of hundreds of experienced coaches in a packed hall who had just heard from an Olympic champion.

Then there was the trip to Bad Blankenberg in East Germany in 1989 as a member of the UK delegation to the XV Congress of the European Athletic Coaches Association in the middle of the cold war. Even the journey to get there was educational in many ways – through the infamous Checkpoint Charlie, travelling thereafter in a coach with blacked out windows and so on. Travelling with the top coaches, sharing information, techniques and knowledge was a tremendous experience for Iain and the information which he gained was shared with others back home in Scotland because he was not selfish with the knowledge. Frank had him involved in coach education from early on and he was a regular speaker at the SAAA/SWAAA courses at Inverclyde.

When we look at the many successes Iain had with many athletes at international, Commonwealth, European, World Championships and Olympic Games, we really want to see how he went about his work, what his guiding principals were in practical terms..

The attention to the individual athlete is always in any conversation with Iain about coaching. He also says that it is not always the international standard athlete who is the highlight for the coach at any given time. You succeed best when you help each individual performer to maximise what they can achieve with their own ability whatever their level. Certainly those who have seen him coaching at club level know that the range of talents with which he worked was wide – he was not a coach who only operated in the upper echelons of athletics.

As far as dealing with athletes is concerned, it is vital that the athlete understands what the session is seeking, what the session is teaching and/or what the activity is working to achieve. The coach can see the movement patterns but only the athlete can sense/feel the kinaesthetic cues ie the feelings/sensations in their neuromuscular system. Learning to ‘feel’ the movement patterns and report appropriately is where the athlete helps the coach. This effective interaction is vital in getting technique precise, for that athlete, allowing the athlete to ‘feel’ the performance, and continually seek to replicate optimal sensation to underpin optimal performance outcomes. The old adage ‘if you can’t do it right slowly you won’t do it right at speed’ should advise the journey to optimal technique supporting optimal performance.

Coaches have athletes come to them at varying stages of their career and when you have been as successful a coach as Iain, sprinters of a high standard come looking for whatever will give them a bit extra, lift them up to a higher level of competition. In that case, the coach fulfils a different function. He becomes an advisor or a consultant. After all, he says, the coach does not necessarily know what it is like to step on to the track, in front of 1000’s of spectators at an Olympic Games – the athlete learns. The coach wants the athlete to fulfil his ambition and they work together to do that. Of course, that depends on the coach having the knowledge in the first place.

That Iain had the skill and pedigree to assist any athlete in the country is shown in many ways but probably best by Sandra Whittaker’s career. An extract from her own account of training with Iain (seen in its entirety at the link above) reads

“When I joined Glasgow Athletic Club I was fortunate enough to be placed in the sprints training group which Iain Robertson coached. Within the first year Iain had quickly recognised my potential and approached my parents to ask if they could bring me to training more than once a week as he said he felt he could really make something of me. After discussion, my parents committed to taking me out to Scotstoun three times a week and Bellahouston one day a week. This was the start of great things to come.” “Our training programmes were very challenging, but with Iain’s support and encouragement we got through them, sometimes on our knees by the end of a session.”

Early recognition, get the parents not just on-side but prepared to help in an active fashion, and being able to make the athlete work hard. From these beginnings Sandra went on to perform at the very highest level. Maybe her best performances were

(a) in the World Championships in Helsinki in 1983 when she was eliminated in her Heat of the 200m by just one one-thousandth of a second in a talent packed race with Merlene Ottey, Florence Griffith, Angela Bailey and Marisa Masullo in front of her. It was four to qualify regardless of times and she ran faster than 12 (twelve) of the 16 who qualified for the semi-finals. It should also be noted that Sandra’s quarter-final was run into a -0.3 m/s headwind while the other three races benefited from wind assistance that was never less than +1.0 m/s.

and

(b) in the Olympic Games in Los Angeles in 1984. She was third in her Heat in 23.22, fifth in the quarter final in 22.98 and failed to qualify for the semi-finals. Runners in front of her were Bacoul (France) in 22.57, Brisco Hooks (USA and the ultimate winner) in 22.78, Bailey (Canada) and Davis (Bahamas) both in 22.97. Another ferocious Heat, less than 2 tenths behind second and only 1 one hundredth behind third and fourth. Faster than 7 of the sixteen who qualified for the semi-final. she was most unfortunate.

She had been very carefully prepared, racing against the very best in the world there was no one better prepared physically and she certainly did not ‘blow it’ mentally. It says a lot for her and for Iain’s preparation.

It was a time of course when athletes from many countries were involved in drug abuse and the athletes from the Soviet bloc countries were particularly understood to be experimenting with various substances and combinations of substances. When Sandra twice missed out on progressing by the narrowest of margins one has to wonder. Iain is quite philosophical about it and none of his athletes were using anything illegal. There was one regret though. The Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh in 1986 saw Sandra come away with a bronze medal in the 200m behind Angela Issajenko of Canada and Kathy Cook of England. After the Ben Johnson doping scandal and the Canadian Dubin inquiry in Canada, Issajenko confessed under oath to doping offences and gave chapter and verse on what she had been taking and when. The period encompassed the ’86 Games. Iain wrote to the governing body requesting that the result of the Women’s 200m be looked at again in view of what had been admitted at the Dubin investigation but nothing was done about it. In view of the fact that several such cases have resulted in athletes places in championship races being upgraded after doping offences were discovered, there is a clear case for the situation to be reviewed.

None of this of course takes away from the remarkable coaching career of a remarkable man – or of the wonderful running of his athletes who all worked hard for him as well as for themselves.

Back to Iain Robertson