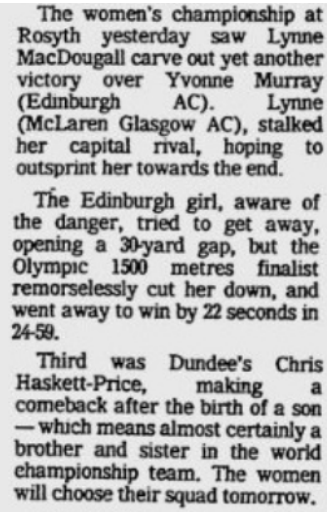

Running in the Six Stage Relays in 2011

Iain Robertson has been a member of Clydesdale Harriers since the end of the 1980’s and been the kind of member that all clubs need – a regular attender on training nights, a runner who is dependable and gives his best every time out; if he is prepared to be elected to the committee then that’s a bonus. Iain ticked all the boxes. We all knew that Ian was a good runner but no one expected the degree of excellence in track running that he displayed when he became a 35 year old competitor in Masters events. We will come to that later but we should start with his own view of his career and his attitude to the sport as explained in his replies to the questionnaire.

Name: Iain Robertson

DoB : 18/01/1978

Club/s: Clydesdale Harriers

Occupation: Chartered Surveyor

Events: 800m to Half Marathon

Personal bests?

400m: 55.17 Kilmarnock, 2016

800m: 2.01.20 Gothenburg, Sweden 2012

1500m: 4.12.61 Gothenburg, Sweden 2012

3000m: 9.55.24 Grangemouth 2010

5k: 17.39 Dunky Wright Road Race 2009

10K: 37.30 Glasgow 2008

Half Marathon: 1.23.43 Balloch to Clydebank 2010

Can you give some details of sporting activity development:

How did you get into the sport initially?

In first year at Braidfield High School, I volunteered to take part in a schools cross country race at Braidfield Farm. After the race, my P.E. teacher, Mr Chudleigh, asked me if I’d enjoyed it. I said I had and he then pointed me in the direction of Derek McGinley who was there watching the races. I spoke to Derek and he invited me and a couple of my friends to come down to Whitecrook the following Tuesday. I went down to the club on the Tuesday and met the other boys Derek was coaching, they were a good group. Derek told me a bit more about the training and competitions I could get involved in. I decided that I wanted to be a part of it, so I became a Clydesdale Harrier.

Has any individual or group of individuals had a marked influence on your attitude or performances?

Derek McGinley – Derek was the first big influence in my early years getting to know the sport. He was generous with his time and you felt like he genuinely cared about athletics and the athletes he was coaching. He was always there with a bit of advice or encouragement and he taught you about discipline and etiquette as well as how to train. I remember being surprised one morning when I was running a 1500m race at Braidfield High in the school sports. Shortly before the race started, Derek appeared at the side of the track to watch. He didn’t have to do that, but I really appreciated it.

I had drifted away from the sport after I left school and went to University. After I graduated, I started doing a bit of running again to improve my fitness. A short while later I met Derek by chance in Clydebank. He was pleased when I told him I’d been running again. He told me about a training group who went to Clydebank Business Park on a Tuesday and said I’d be welcome to come along. I didn’t realise quite how high the standard of training was until I went along. Allan Adams, Charlie Thomson and James Austin were all regulars. I was out of my depth but the guys made me feel welcome. I joined in and certainly got fitter!

Derek played a big part in my return to Clydesdale after a few years out. He later said to me that one of his aims was to see the boys he’d coached go on to run as seniors. I was pleased that Derek saw me run as a senior and I will always appreciate what he did for me.

Phil Dolan – I think I was about 28 years old when Phil asked if I’d like to train with his group on Tuesday nights. I went along and it soon became Tuesdays and Thursdays. Phil’s training methods were more focused and structured than what I’d been doing before and it really opened my eyes. His initial assessment of me was that I should be running faster and if I followed his advice, I would. There were a few talented young athletes in the group at the time including Peter Bowman and Ryan Savage. I enjoyed the training and I was able to see improved results pretty quickly. Phil’s advice and influence changed my perceptions of what I was capable of and over the next few years, I would say that my running improved significantly.

Phil has been the biggest influence on me in my athletics career. He taught me a lot about preparing for races, adapting the training to suit different circumstances. He’s provided me with endless support, guidance and encouragement. I’ve learned a lot from hearing about his experience in the sport. I knew I would never get to the level that Phil achieved, but he made me believe I could be better and to work hard to achieve my own personal goals. His training is always fun and he’s never short of a tale to tell, he makes it enjoyable. All of my PBs have been achieved under Phil’s guidance but perhaps even more importantly, Phil’s judgement in the build up to key races is excellent. He has helped me to reach my season’s best performance at just the right time on many occasions. He has clearly helped me to be a better runner and get a lot more out of the sport.

Something about attitude:

What exactly did you get out of the sport?

I’ve really enjoyed being part of the sport. I was never the fastest but I felt it was something I could do reasonably well. I’ve tried lots of different sports and activities but athletics is the only sport I’ve really taken seriously in a competitive sense. I liked the challenge and the satisfaction of feeling that I’d achieved something. Over the years, it’s helped my physical health and my mental wellbeing. I’ve met some great people and travelled to lots of different places so it’s given me a lot of experiences that I wouldn’t have had otherwise.

Can you describe your general attitude to the sport?

I think my general attitude is to have a healthy lifestyle and to participate to the best of my ability. I place more importance on being involved in the sport rather than being the best, but I like to think I always try my best. I particularly enjoy the team events like relays and league competitions, where my own performance is also contributing towards the team as well. It’s a different feeling from running purely for yourself. Running has also been an outlet for me to relax and de-stress outside of work.

What do you think was your best event?

I would say that the 800m has been my best event over the years. I think my times and performances would say that I’ve been more competitive in the 800m that any other event. I really enjoyed the event as a schoolboy. As a senior, I didn’t really think I’d do much track running. But when I got a couple of chances to run in the Men’s League I got a taste for it again. When I started training with Phil, the 800m and 1500m became more of a focus and my times were getting quicker. I’ve taken this into the masters events and I generally have more success in the 800m than anything else.

What do you consider your best ever performances?

I think my 800m and 1500m pbs over two days in Gothenburg 2012 were my best performances. Winning the 2014 British Masters 800m in Birmingham with a time of 2.02.31 was definitely a highlight for me. Winning a number of Scottish Masters medals over 800m and 1500m was very pleasing as well.

What has running brought you that you would not have wanted to miss?

There are lots of races I remember being involved in which have given me a great sense of satisfaction. Running personal bests or achieving a particular goal is always a rewarding feeling.

I really value the experience and feeling of just running whether I’m on my own or in a group. I always feel better after a run.

One of the main experiences that stands out are the two trips to Gothenburg. Phil took a group out there in 2009 but unfortunately I couldn’t go. Johnathan Farrell and Peter Bowman were keen to go back over, so I went with them in 2011 and 2012 and I really enjoyed both trips. Running two pbs in my favourite events at the time in 2012 was particularly memorable.

The camaraderie of the training groups I’ve been part of has been very rewarding. You feel a common purpose. Everyone is helping and encouraging each other to improve and you celebrate each other’s achievements. I wouldn’t have wanted to miss the different people I’ve met and friendships I’ve made.

In truth, I really wouldn’t have wanted to miss any of it!

Can you give any details of your training? (now or in the past)

I’ve never been someone who runs high weekly mileage. I found that I would often pick up injuries if I did too much. Phil helped me a bit by guiding me as to how to increase my training and avoid getting injuries and I definitely trained harder and with more purpose under his guidance. Throughout the period I have been coached by Phil, I would say my running has been pretty consistent. A large part of that would be down to training consistently. I would run six days a week most weeks. A typical week would be two or three interval sessions with some easier runs in between. At the weekend I would do a longer run of around 90 minutes. The interval training would vary depending on the time of year and what races were coming up. Winter being more grass based intervals over longer distances and summer would more track based with shorter, faster repetitions.

Now, as I’m getting closer to 50, I find it helps to have some extra rest days to help with recovery. I also try to cross train a bit by cycling or going to the gym. At the moment, my aim is to keep going for as long as I can and try to be as fit as I can.

–

The responses above are thoughtful, informative and revealing of his attitude to the sports. He refers to Derek McGinley who was a much under rated coach. Derek coached only boys at first and then followed the athletes as they grew older. Although he seemed to prefer the endurance events, he worked to give the athletes under his guidance a taste for all events because they had different talents and he produced good athletes in the sprints, in endurance events, in the javelin and in the long jump. Obviously some moved to other club coaches for specialist guidance, often at Derek’s prompting, but all gained from his input. Phil, of course was a top class endurance athlete in his own right having won international honours on the track and over the country.

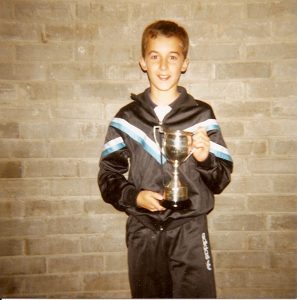

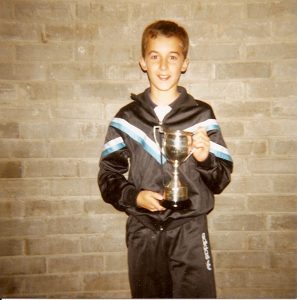

Iain as a boy is shown above holding the Weirs Pump Trophy which he won it at the school sports. Derek McGinley asked him to bring it down the club to have a photograph taken with it. Derek had many photographs of his athletes with club (and other) trophies – it was good for their morale to have a permanent memento of such moments.

Iain joined the club in 1989 when the Boys age groups were particularly strong. Bobby Harris, Jamie Hood, Alan Moore, Robert Emmanuel, Ronnie Armstrong and others made at least two strong teams for any race over the country and gave Derek real difficulty in selecting track and field teams. It is maybe salutary to note that although they all rendered sterling service to the club, Ian is the only one still running and racing in the 21st century. Not as obvious as some of the others, but Iain was a natural runner who developed at his own pace – we all mature at different ages – to become a medal and championship winner at GB AAA’s level. He was a good team member who turned out in almost every event that the club contested, track and country, and added to club successes at the time. However, as he says in his reply above, he drifted away from the sport while he was studying at school and university. There was also the factor that some of his friends in the club as boys had also left for a variety of reasons and several scattered to other areas for tertiary education – at least one went to Aberdeen and took up boxing as a sport, another to Dundee where ski boarding became a big part of his free time. We take up our look at Iain’s career after he returned and was competing as a senior man.

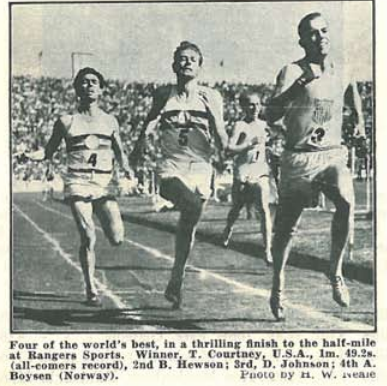

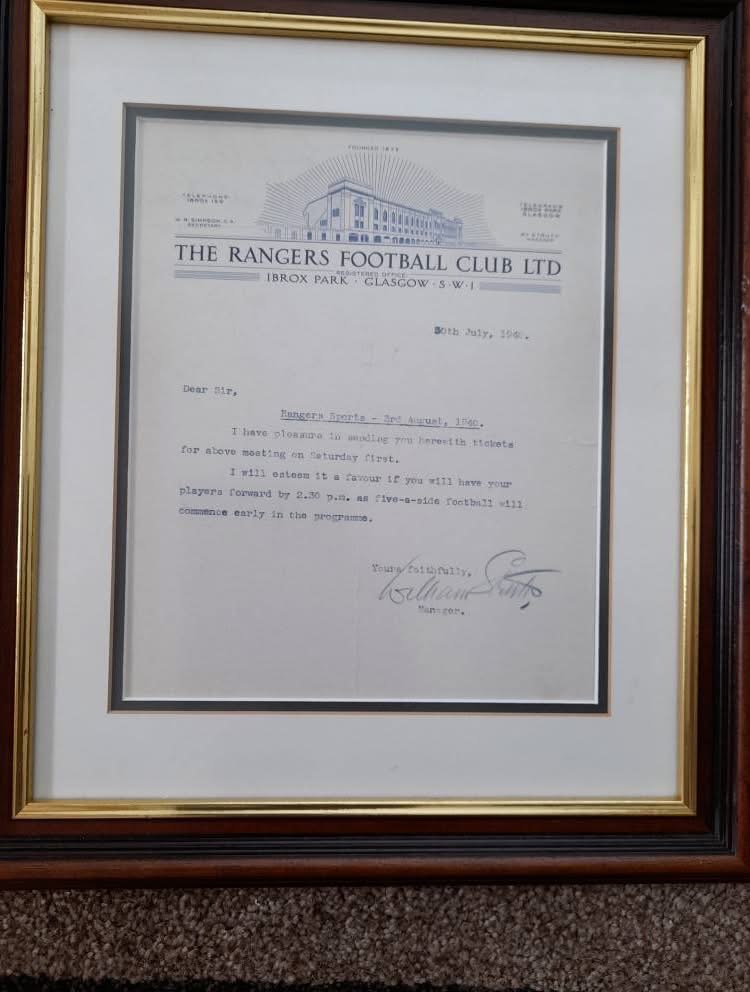

Running in the Scottish Masters Indoor Championships in 2015

Iain had always run in track events and performed well, particularly in the middle distance events without starring in any one of them. And then from at least June of 2008 Iain’s name was appearing more in the track columns and in September that year, the ‘Daily Record’ reported as follows.

“Clydesdale Harrier Iain Robertson ran a personal best time in the Glasgow Green 10K last week – despite focusing his summer training on track racing. The Harrier ran in a personal best of 37:30 to come 31st from a field of 6089, which was a huge achievement, given it was the furthest he had run for several months.”

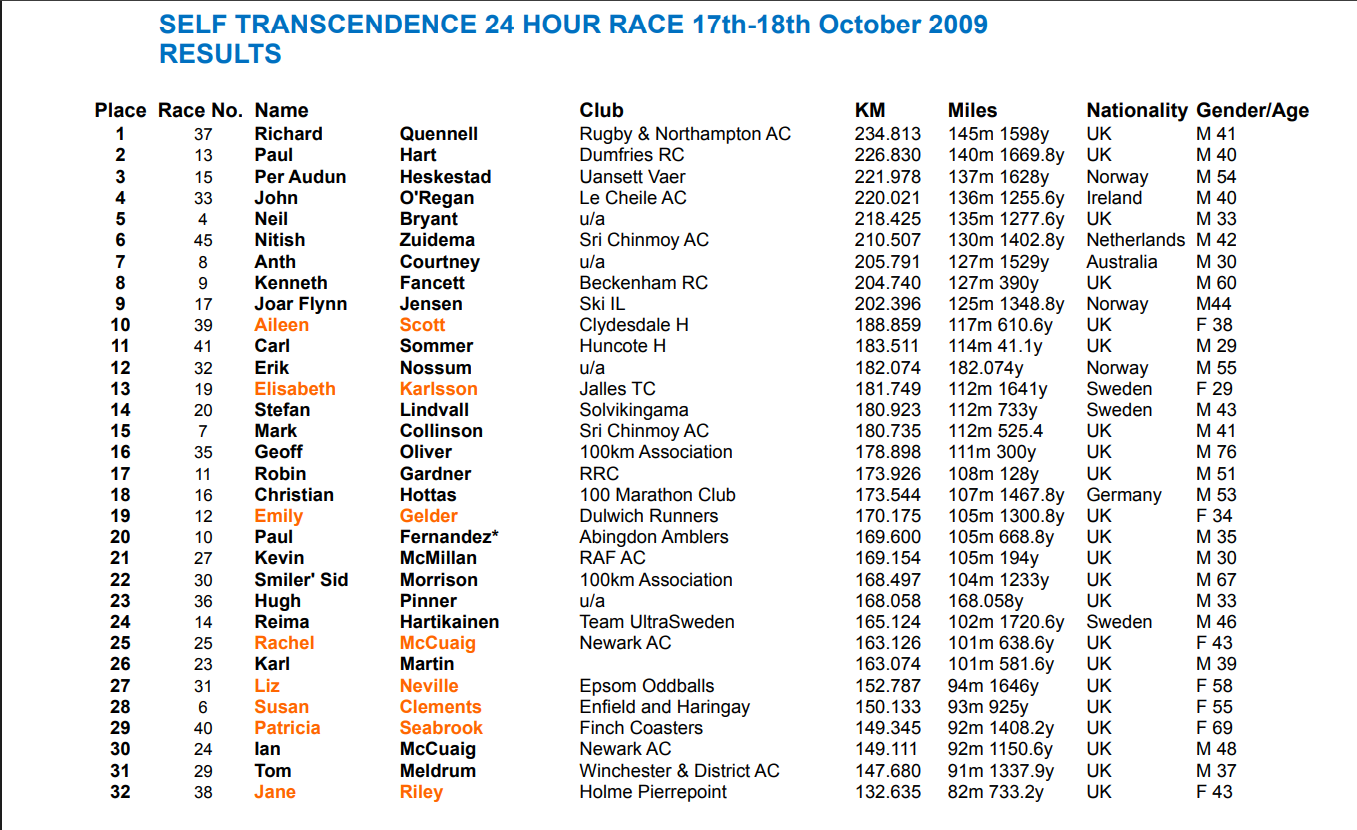

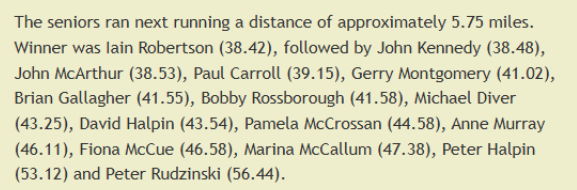

It did not mean that he had given up on cross-country or road racing. For instance in November 2008 he turned out in the West District championships on a heavy, muddy trail at Lenzie, and later in the same winter season he became club champion over the country and in the National he was second club man to finish behind international hill runner, Prasad Prasad. He also won his first club championship in 2009. He knew at the time that he was quite fit but given the quality of the opposition, he had no expectations of himself as they faced the starter. It was held over three laps of the local Braidfield Farm course – one known and feared by many in the land. It was a ferocious trail with several serious hills, barbed wire fencing and plenty of mud. He led through the first lap and, like everybody in the race, tired a bit on the second and the three leaders had a real battle on the last lap where Iain closed the gap and then sprinted away to finish. winning from John McArthur, a track steeplechase runner and a former British army duathlon champion, and John Kennedy who was a noted ultra distance runner who also ran in many serious hill races such as the Stuc a Chroin in Strathyre. Two notable scalps for any cross-country runner. The official results:

It should be noted too that he was elected to the club committee for the first time on 17th April 2009.

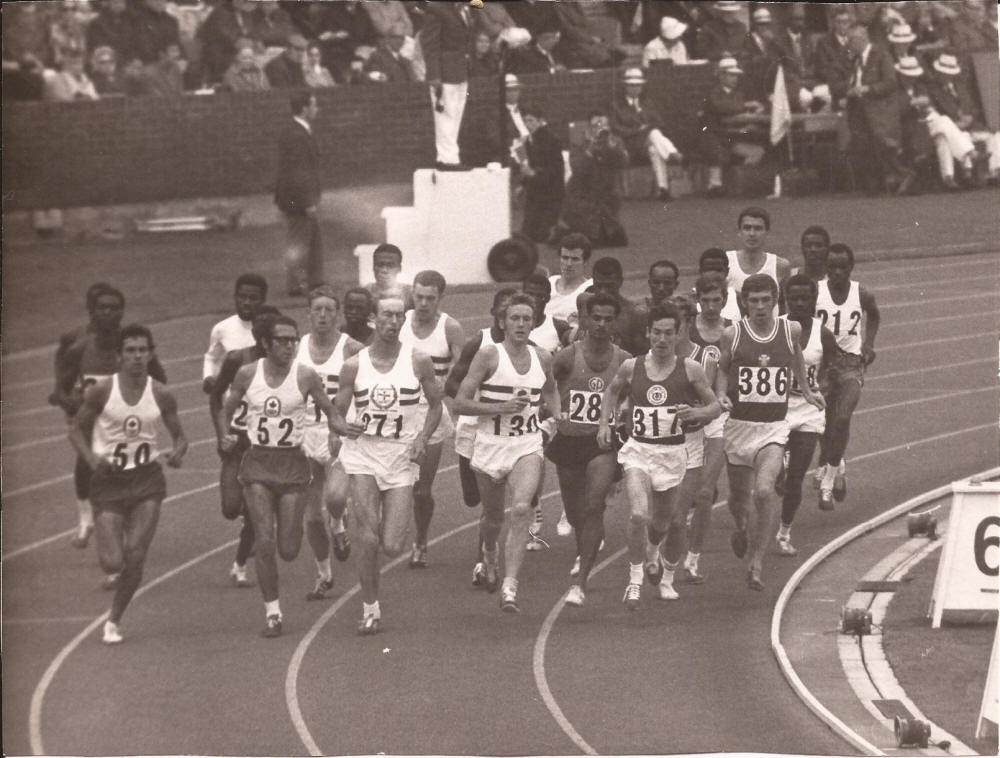

His normal racing pattern continued into 2010 with races in the Scottish Athletics League and the Central & South Scotland League but there was a new feature in the programme. On 14th June he drove down to the Stretford Track in Manchester for the first time with Peter Bowman, a good runner with pb’s of 25.29 (200), 53.26 (400) and 1:57.93 (800) who also ran well over the country, and Johnathan Farrell, a Scottish Schools internationalist sprinter, where they stayed overnight. There are monthly open meetings at Stretford and the elite British Milers Club hold races at 800m and 1500m in alternate months. The competition is always fierce. Iain ran in the 800m the following day and, despite being a bit short of training and having done the more-than-200-miles drive down, he ran 2:04. He travelled even further the following year when he went to Gothenburg in July but it was a much busier period for him with the Power of 10 website listing 22 races – and that was probably not the complete tally. The range of events was wide too: 400m, 800m, 1500m, 3000m, part of relay teams at 4 x 100 and 4 x 400 plus the long jump in one CSS League match where he won the A string event and Discus where he was 3rd A string competitor. Best performance in the 800m was 2:02.27 in the 800m at the Scottish Senior Championships in Glasgow on 16th July.

Shortly before that he had travelled with Peter and Johnathan to the Gothenburg Youth Games where he ran in the 1500m on the 9th turning in a time of 4:19.85 running in the magnificent Ullevi Stadium. The next day, and more familiar with the arena and the atmosphere there he ran in the 800m clocking 2:04.17. Again, Phil had something to do with another very good run away from home. When he found out that Iain was heading to London to see the tennis at Wimbledon, he suggested he find some competition while there. Iain asked around, even asking a local League if he could run as a guest, but with no success. again. But it was Phil to the rescue again. Let Iain tell the tale in his own words: “The race in London when I went down to Wimbledon was a 1500m race on 30 June which was the weekend before my trip to Gothenburg in 2012. Phil and I had identified this race and I had been was sending emails and making phone calls trying to arrange to run as a guest. Right up until the morning of the race I thought that I wouldn’t be running as I hadn’t received any response. So I was surprised when Phil phoned me on the morning of the race day to say it was all sorted! He had gone directly to one of the competing clubs, Hercules Wimbledon and they to arranged for me to run. The event was the Southern Men’s League Division 1 at the Sutton Arena, Carshalton, London. It was a good competitive race and I finished fourth in a time of 4.24. Unfortunately the official result has me shown as AN Other! I seem to remember that the administrators and officials weren’t particularly friendly or welcoming but the guys from Hercules Wimbledon were fantastic. It was a great experience and I think it was exactly the preparation I needed before heading off to Gothenburg.”

It had been a very busy period for him with meetings on 3rd July (Wishaw), 9th and 10th July (Gothenburg), 16th July (Glasgow). The season had included 4 Scottish Athletics League matches and 4 CSS League Matches. On the administration front in the club, he was elected club Vice-Captain at the AGM in April 2011

Came 2012 and Iain ran in 5 SAL (Scottish Athletics League) meetings and 6 CSSL (Central & South of Scotland League) matches, mainly in 400 (best performance 56.20) and 800m (2:03.72) events with few 1500m and one 3000m. He also competed in the Long Jump and discus. Away from the track he ran as an individual and also in championships (county, district and national) and relays. The big event of the summer season however was a return trip with Johnathan Farrell and Peter Bowman to Gothenburg where on 7th July he turned out in the 1500m recording a time of 4:12.61 and then on 8th July he ran in the 800m finishing fourth in his race in 2:01..2. These trips, allied to the increasing specialisation in 400/800 with the occasional over distance 1500 and 3000m were to stand him in good stead in future years.

The Power of Ten statistics show him as running in every CSSL and SAL meeting across the length of the country but there were some other very interesting events appearing. Scottish Masters events (for athletes aged 35 or over) started to show up with Iain racing in the indoor championships on 10th February over 1500m in the Emirates Arena to be sixth in 4:53.11, following up with the outdoor championships 800m at Grangemouth on 16th June and finishing second in 2:02.96. He was also moving up a step or two in competition standards when he competed in the British Masters Championships 15th September in Birmingham where he finished second in 2:04.2. There was a transatlantic race when he ran in the York University Twilight Meeting in in Toronto, Canada, on 23rd June where in the 800m he was timed at 2:03.82 finishing second in the third race. How did York get into the programme? It was down to two things – Iain was on holiday in Canada and Phil had advised him to get into any races that were going when he got there. Good advice – it is too easy if you are racing only in your own district of your own country and staying in a wee comfort zone. York is just outside Toronto and that’s how Iain and his wife got there for the event. Like all athletes he had conversations with other runners and got on well with a Canadian coach at the meet. So well in fact that he was given a lift back to Toronto by him. The challenge of racing outside of the normal area against runners you don’t know broadens experience and makes a runner better. The variety of races against very good athletes all over Britain and abroad in Sweden and Canada meant that Iain had been racing outside of the comfort zone that so many seniors and budding seniors inhabit when they only race locally and against known opposition. He clearly enjoyed the challenge – and every runner needs a challenge if he is to succeed. At home he continued to run cross country races and relays for the club – as dependable as ever and a great example to the younger runners.

In 2014 as a Men’s Veteran 35 Iain followed his usual summer pattern of competing in the SAL and CSSL fixtures in 100m, 200m, 400m, 800m, 1500m but added more field events to his contribution to team success by covering Long Jump, Shot Putt and Javelin. However 2014 was the year that Iain drew himself to the attention of the wider British veterans scene by his performances in his category. In the Scottish Masters Championships at the Emirates on 15th June he was 2nd in the 800 metres in 2:04.10 and 3rd in the 1500m with a time of 4:21.92. Then on 10th August in the higher level of British veterans competition he went one better by winning the 800m in 2:02.31 at Birmingham. These performances would be noted by the actual and potential competition and they would now be looking out for him.

Iain ran over the country too and represented the club again all the relay and cross-country championships that winter and into 2015. He varied the winter diet of running by turning out in the National Masters Indoor Championships on 31st January 2015, held again in the Emirates arena, Glasgow, and winning the 800m in 2:08.25. Summer 2015 again saw Iain run in all the club league races as well as the major championships. The Scottish Masters came first being held on 11th July where he was 2nd in the 800m in 2:05.8 and 2nd in the 1500m in 4:32.1. Two weeks later – 26th July in Birmingham, saw him face the starter in the 800m, this time finishing in 3rd place in 2:03.98. On 15th August he took part in the Scottish Senior Championships 800m where he was timed at 2;04.71.

Iain was quite busy away from the round of League fixtures in 2016. 3 GB medals in three years over his favourite distance – could he maintain the record? We only need to look at his performances away from the League matches. On 14th February, almost at the end of his winter season of racing on the road and over the country for the club, he went to the Scottish Masters Indoor Championships in Glasgow and finished second in the 800m in 2:10.63 and third in the 1500m in 4:28.30. Iain ended the 2016/17 season with two club championship events under his belt. He won the Hannah Cup cross-country handicap for the trophy which had been donated by club member Andrew Hannah who had won the national cross-country championships five times in a row at the start of the 20th century; and he also won the club cross-country championships. His talents over the country were also on display when he was first club runner to finish in the national championships, a feat which he replicated in 2020.

The first championships of the outdoor season were the Scottish Masters Championships in Aberdeen on 2nd July: he left with a first in the 800 in 2:05.94 and a second in the 1500m in 4:29.84. He then travelled to Stretford for the BMC GP 800 on 19th July. There are a whole series of races at the distance at these meets and Iain won his race with 2:02.81. There was a bit of a wait before the BMAF Championships at Birmingham on 18th September. That did not affect Iain’s running too much and he was fourth in 2:01.98.

Summer 2017 was one in which Iain did no championships – veterans or senior, Scottish or British – other than the Scottish veterans at the Emirates in March where he won the 800 in 2:06.72 and was third in the 1500m in 4:20.7. The reason was quite simple – he was married that year and we see that he ran in the Melbourne Parkrun in Australia on 8th July and the East Coast Parkrun on 22nd July turning in times of 19:52 and 20:42 respectively. The East Coast Parkrun is in Singapore and this brought the number of countries competed in so far to six – Scotland, England, Sweden, Canada, Australia and Singapore. This time, it was his wife (they were on holiday) who wanted to do the two parkruns – she was a runner but not a competitive one. Iain went along and they ran in the two events. In 2018 the first championship was the Masters indoor championship on 4th February at the Emirates, Glasgow. Here, Iain finished 2nd in 2:08.62. Outdoors in 2018 he began the championship season in May with a run in the West District Championships at Kilmarnock, recording 2:05.98 before tackling both 800m and 1500m in the Scottish Masters at Grangemouth on 14th July. This time he won the 800m bringing his gold medal total for the event to four with 2:07.44 but could only manage 5th place in the 1500m in a time of 4:34.88. The season was rounded off at Birmingham with another medal at the BMAF championships 800m when he was 3rd in a time of 2:05.07.

2019 was his first year as a vet 40 when he moved up an age group. Given his background he was still of course supporting the club in every League match that he could possibly attend and was a regular in the Long Jump with occasional appearances in other field events. There was no indoor championship and Iain started his season at the West District Championship with an 800m in 2:07.88. The Scottish Masters was held again at Grangemouth when he was 3rd in the 400m with a time of 56.56 and another 3rd in the 800 in 2:06.58. He was only marginally quicker when he was 4th at the BMAF championships on 11th August in 2:06.47. In 2020 the Scottish Masters indoor championship was at the Emirates Stadium 2nd February when he was 2nd in the 800m in 2:08.59. and 3rd in the 1500 in 4:26.86.

Like all athletes, Iain’s championships and racing generally were seriously upset by the Covid pandemic which swept the entire world and he next appears in a championship in 2023. That year he ran in the Scottish Masters indoor championships in Glasgow, finishing 1st M45 in the 800m in 2:08.44 and 4th in the 1500m in 4:40.98. He was still running in the cross-country and road programme through the winter and was seen in many championships including Dunbartonshire, Renfrewshire, six-stage road relay, west district relay and national relay championships. His track form seemed to have shaded off a bit in 2024 causing him to miss all the Scotttish Athletics League fixtures but he was well to the fore again in the Scottish Masters championships where he was 2nd M45 in the 800m in 2:10.43 and first in the 1500 in 4:41.10. These times were season’s bests with a 63.44 for the 400m.

His championships performances over this period can be summed up in the following tables

Scottish Masters Outdoor Championships

| Year |

Age Group |

Event |

Position |

Time |

| 2013 |

M35 |

800m |

1st |

2:02.96 |

| 2014 |

M35 |

800m |

1st |

2:02.80 |

| 2015 |

M35 |

800m |

2nd |

2:05.80 |

| |

M35 |

1500m |

2nd |

4:32.13 |

| 2016 |

M35 |

800m |

1st |

2:05.84 |

| |

M35 |

1500m |

2nd |

4:29.83 |

| 2017 |

M35 |

– |

– |

– |

| 2018 |

M40 |

800m |

1st |

2:07.44 |

| |

M40 |

1500m |

5th |

4:34.88 |

| 2019 |

M40 |

400m |

2nd |

56.56 |

| |

M40 |

800m |

2nd |

2:06.58 |

British Masters Athletic Federation

| Year |

Age Group |

Event |

Position |

Time |

| 2013 |

M35 |

800m |

3rd |

2:04.2 |

| 2014 |

M35 |

800m |

1st |

2:02.31 |

| 2015 |

M35 |

800m |

3rd |

2:03.98 |

| 2016 |

M35 |

800m |

4th |

2:01.98 |

| 2017 |

M35 |

– |

– |

– |

| 2018 |

M40 |

800m |

3rd |

2:05.07 |

| 2019 |

M40 |

800m |

4th |

2:06.47 |

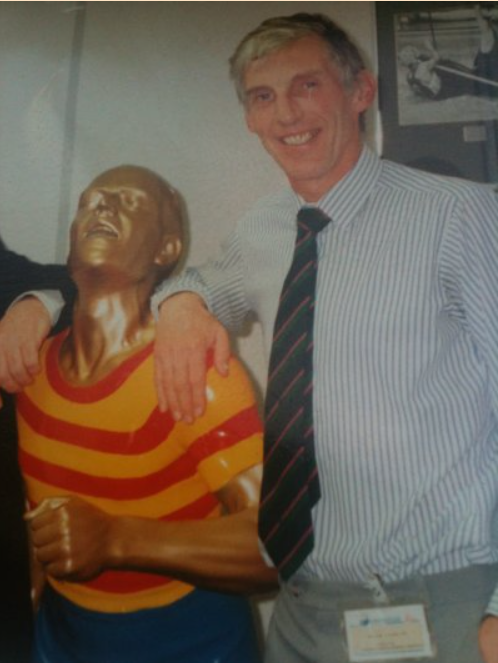

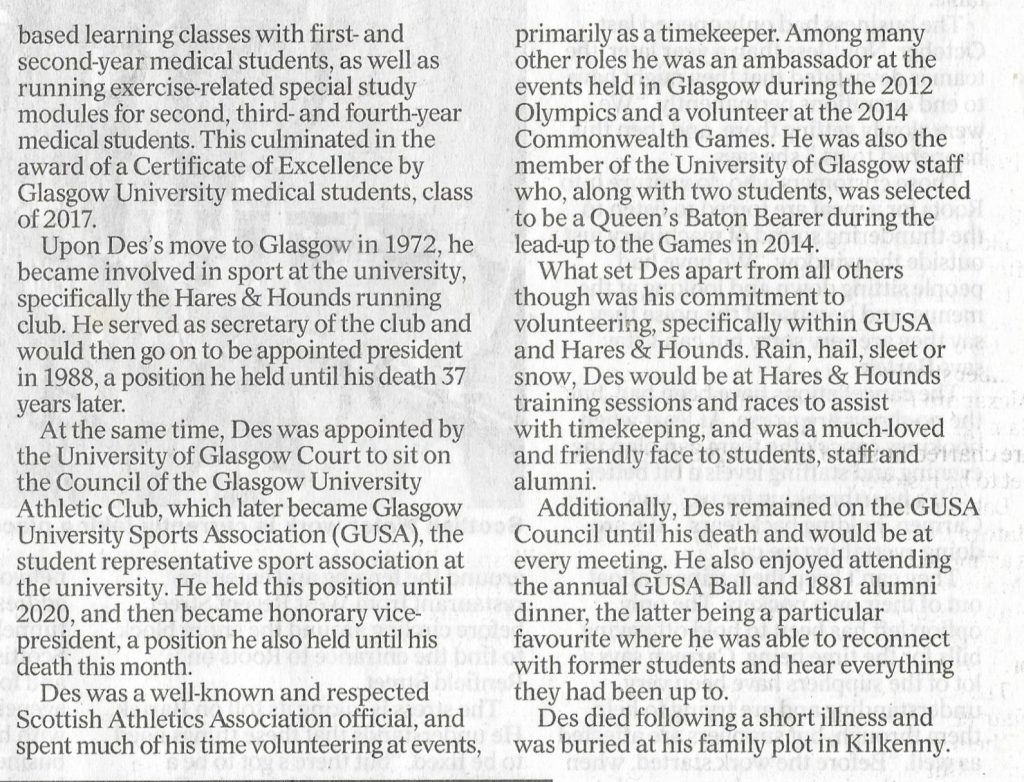

Iain in 2025 Scottish Masters indoor championships

Iain’s performances on the track as a Masters athlete, right from the beginning as an M35 to date have been excellent and they show no signs of letting up. This year, 2015 as a MV45, he has raced in the Scottish |Masters Indoor Championship on where he was second in the 800m in 2:12.90 and fourth in the 1500m in 4:46.48. Later in the year, 27th July, he had a double first – 800m in 2:11.01 and 1500m in 4:38.80. See the picture below.

Where does he go from here? When asked about his future in the sport Iain was clear that he wanted to carry on running but maybe not the intense competition of Track League matches. In all probability he tells us he will run in park runs, over the country and on the roads – the question is whether he will compete in veterans races.