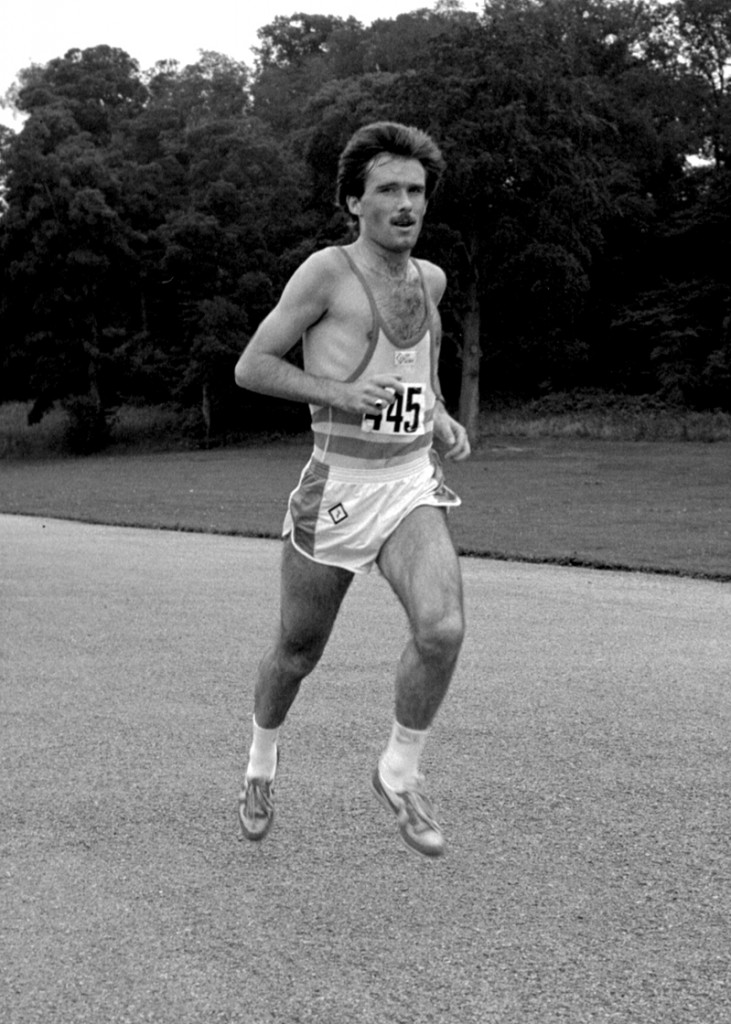

Alastair Wood came to marathon running with a record of athletic achievement at all levels of the sport that might have justified him in retiring or stopping. Instead he went on to become one of the great figures of Scottish and British distance running. Among the many honours that were justly awarded to him was the Achilles Club gold medal. The Achilles Club is an elite and exclusive athletics club composed only of students at Oxford and Cambridge Universities. Founded in 1920 it has added a great deal to the sport and is known and respected all over the globe. Since 1949, the Achilles Club has awarded annually two gold medals, for the best performance by a club member on either Track or Field. Recipients of the Track award include Roger Bannister, Chris Chataway, Chris Brasher, David Hemery and Richard Nerurkar. The only Scottish athlete to obtain this prestigious medal was Alastair Wood (Oxford University and later Aberdeen AAC), who won twice: in 1962 [when he was a close second (to that year’s European and Empire champion Brian Kilby) in the AAA Marathon; and a splendid fourth in the European Marathon]; and in 1966 [when he is reported to have run 2.16.06, and also set a new European record of 2.13.45 in the Forres marathon. For some obscure reason, the latter time has never been accepted by the SAAA, but was ratified by the AAA in 1967, and is now recognised by the Association of Road Running Statisticians (www.arrs.net) as the fastest time of the year in 1966]. Alastair was also narrowly pushed into second by Jim Alder in the AAA championships in 1967, with 2.16.21. And yet the present generation of Scottish marathon runners know very little about him.

Like so many marathon men he began as a middle distance track runner. Having been introduced to the sport at Elgin Academy, he really became involved when he went to Aberdeen University. The 1952/53 AU ‘Athletics Alma’ reported, ‘A very useful half miler in A Wood has come forward this year. he should with more training and competition soon break the two minute barrier.’ He himself doesn’t recall doing so, but without too much practising turning in a 4:30 mile and a 14:55 Three Miles. In 1955 however he was third in the SAAA Mile Championship, and after running a 4:15 on the grass track at Westerlands, came under the guidance of the Scottish National Coach, Tony Chapman. After leaving University he went into the RAF and really began training in earnest. In 1975 he won the SAAA Three Miles, in 1958 he won the Six Miles and in 1959 lifted both titles. He had already in April ’59, become the second Scot to run under 29 minutes for the Six Miles when he turned in 29:40.8 in the English SCAAA race, and although not quite so fast set a new Scottish native record for the Three Miles of 13:39. 8 and ran Ten Miles in 49:24.8. He also won the Six Miles in 1960 and 1961. This feat of winning the title four times has only been equalled by Ian Binnie of all the Scottish distance runners. The range of his ability can be seen from the 1960 season when he also ran a Scottish native record for the Three Miles of 13:39.8 and ran Ten Miles in 49:24.6. By 1962 when he turned to marathon running he had six SAAA titles, set records ay 3, 4, 5 and 6 Miles and represented Great Britain at Three Miles, Six Miles and in the Steeplechase.

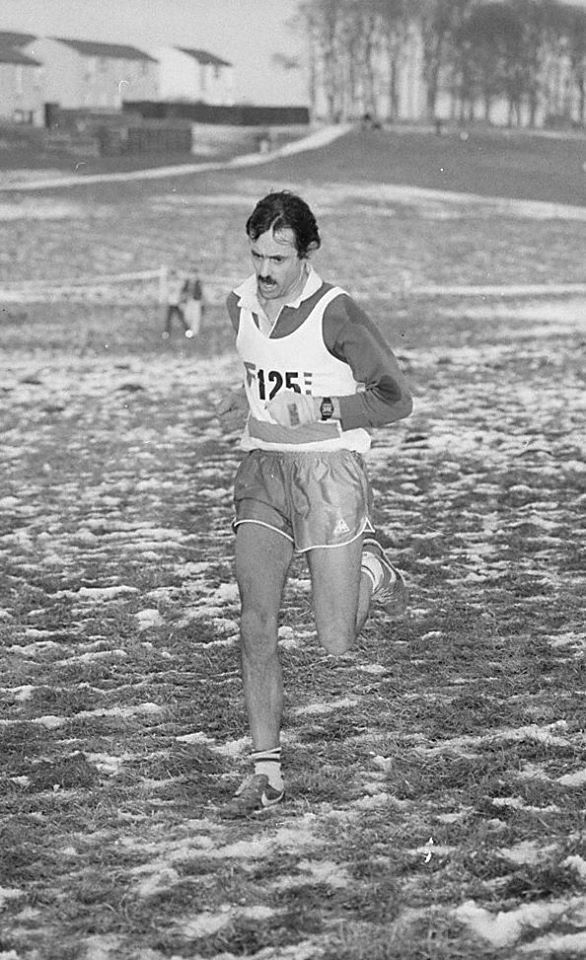

Over the country, Alastair began by winning the Scottish Universities Cross-Country title in 1956 for Aberdeen University at St Andrews. Such was his progress that a mere three years later he won the Scottish title from John McLaren of Victoria Park. he ony narrowly failed to retain it the following year in an epic race with Graham Everett which had Emmet Farrell writing in the ‘Scots Athlete’ saying that the running of the winner must rank among the greatest in the history of the race, almost equally brilliant was the form of the defeated champion, Alastair Wood. This race was followed by another really exceptional run in the International Race held at Hamilton Racecourse in which the spearhead of the team was Wood, Everett and the AAA’s Three Mile Champion, Bruce Tulloh. In the race itself, Alastair was seventh behind Rhadi, Roelants and Merriman, prompting Farrell to say, ‘Scotland, fifth out of eight teams, might have claimed fourth if Everett and Tulloh had run with the distinction of Wood.’

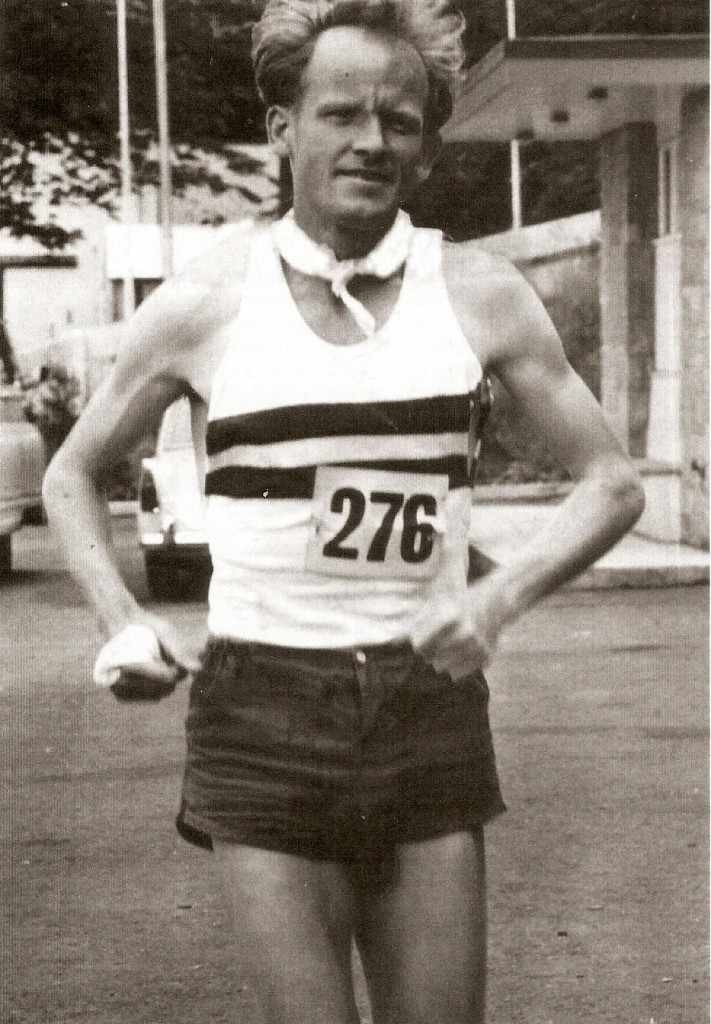

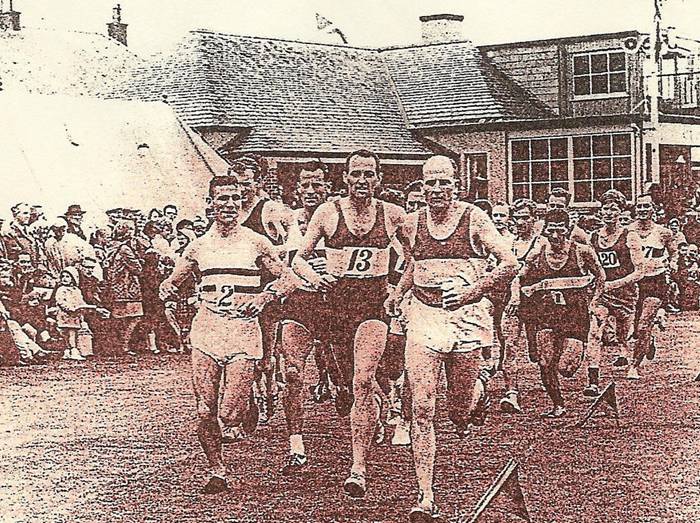

In May 1962, Andy Brown had run a great 2:25:58 for the marathon and was favourite for the SAAA title. In fact Alastair took exactly one minute from the time in winning the championship. He went on to run second in the AAA’s event and gain selection for the team for the European championships in Belgrade. He finished fourth in that race – a magnificent achievement in only his third marathon. Despite being quoted after the race that he was bored with the distance and would run no more marathons, he was far from finished with the race. A few only of the highlights of his subsequent career are set out here.AA title. In fact Alastair took exactly one minute from that time in winning the race. He went on to run second in the AAA’s event and gain selection for the UK team for the European Championships in Belgrade that year. He finished fourth in that race – a magnificent achievement in only his third marathon. Despite being quoted after the race that he was bored with the distance and would run no more marathons, he was far from finished with the race. A few only of the highlights of his subsequent career are set out here.

| Year |

Race |

Time |

Place |

Comments |

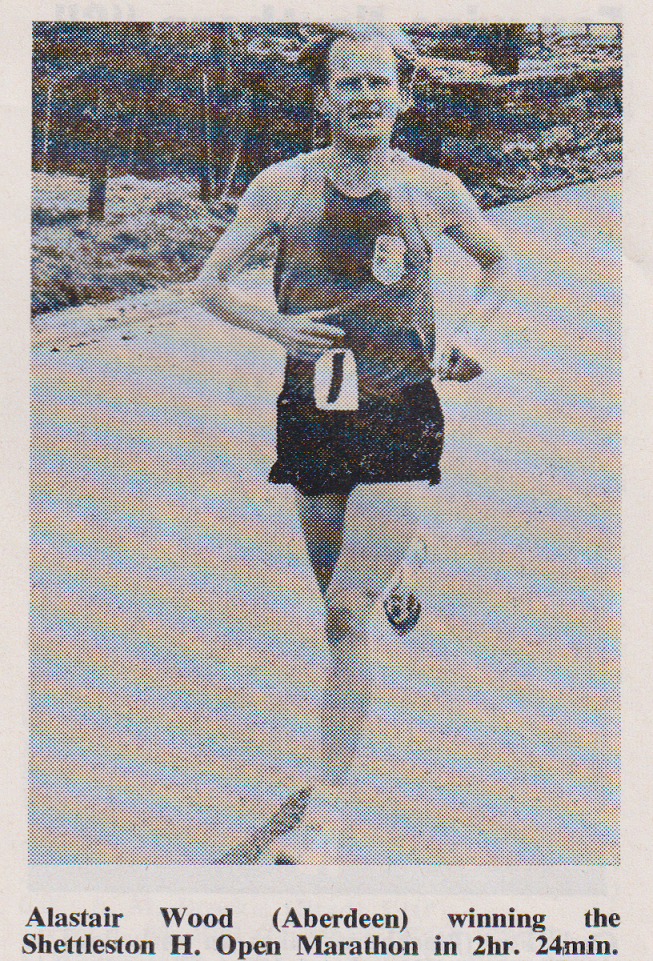

| 1964 |

SAAA Championship |

2:24:00 |

1st |

|

| 1965 |

SAAA Championship |

2:20:46 |

1st |

|

| |

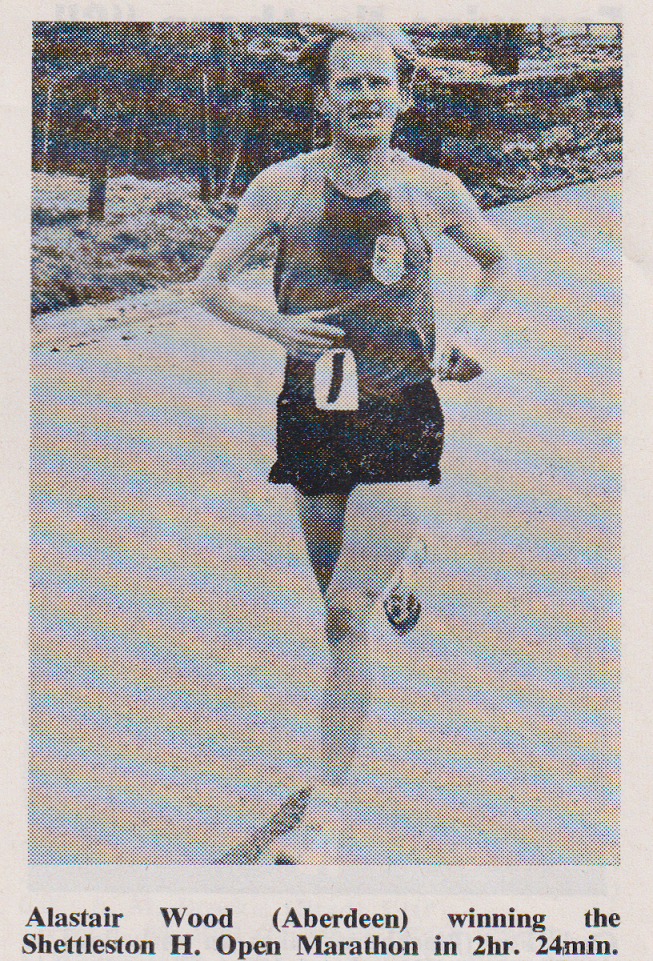

Shettleston Marathon |

2:19:03 |

2nd |

|

| 1966 |

Inverness – Forres |

2:13:45 |

1st |

GB and European Best |

| 1967 |

SAAA Championship |

2:21:26 |

1st |

|

| |

AAA’s Championship |

2:16:01 |

2nd |

|

| 1968 |

SAAA Championship |

2:21:18 |

1st |

|

| 1969 |

Harlow Marathon |

2:19:15 |

1st |

|

| 1970 |

Harlow Marathon |

|

1st |

|

| 1972 |

SAAA Championship |

2:21:02 |

1st |

|

| 1974 |

World Veterans Champs |

2:28:40 |

1st 0+ |

|

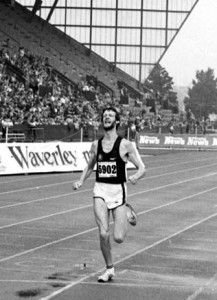

These are only the very bare bones of his marathon career and say nothing of the many many first class races with which his diaries are filled. The European best time of 1966 was never properly recognised and he had to live with the smear that it was a short course for some time. The SAAA did however include it in their list of best times and they are not a body given to charity in matters of this sort. Besides, did not his entire career up to this point indicate that he was indeed capable of this time? His record of six Scottish titles is unequalled and it would be a brave man who forecast a similar one in the years to come.

1966

He has also run well in events beyond the marathon distance. He is credited with Scottish Native Records at 15000m, 20000m and 25000m (sharing the last two with Don Macgregor) and for the two hours run. Probably his best Ultra was in the London to BRighton in 1972 which he won in 5:14:31, a record which stood until 1978 and is still the third best of all time for the course. It was after this rn that he was heard to comment that he felt his legs had been sewn on backwards!

Alastair’s career has been of such length, variety and quality that even a brief summary such as this makes awesome reading, but what of the man himself and his training methods and philosophy? He was quoted in a Road Runners Club publication of 1965 as saying that if running meant the exclusion of all else, he would give up tomorrow. Nevertheless, one who knows him well believes that running is one of the mainsprings of his life – although he abhors athletics bores. Described as an intellectual runner (not in the sense of education endured but rather with respect to his attitude to the sport) his attitudes to training provoke not a little thought. Underlying his attitude to training is his belief that training to runf ast, means running fast. Beginning when he did in the late 50’s, he was totally interval trained up to 1960 and found that he could run well up to and beyond 10 miles on any surface. It is inevitable that while he shares many doubts about the quantity of interval training done in its heyday, he should feel that it still has a great deal to contribute to any training scheme. Any system is dangerous if taken to extremes and this is as true of long, slow distance as it is of interval training.

I would like to quote Alastair direct at this point. ‘The answer to fast running at any distance is to devote a considerable amount of time to moving faster than you intend to race. eg my best time for a mile is :10 but by a lot of hard work I got my ‘cruising speed’ up so that in one session I could run 3 x 1 Mile in 4:15 with a ten-minute recovery.’ Long runs? ‘I agree you need one long run at least, but probably not more than two. You also need a couple of interval/repetition sessions – reps over a relatuvely long distances (880y to Mile) and intervals of say 220y. My fastest marathons came after only three to four weeks of interspersing fastish steady runs of up to 12 – 15 miles on the road with track work-outs of up to 60 x 220 in 33/34 seconds with very short jogs of about 35 seconds in between. As far as the big mileages done now for longer races are concerned, the following comments from an acknowledged master are illuminating. ‘I also discovered the invaluable practice of training every other day. After all, you need some sort of carrot to do 60 x 220 if you are human! So you could train as little as three or four days a week and simply jog a couple of miles to recover on the other days, particularly once you are fit and looking for races and preparing for a particular event. This is exactly what I did when training for my one and only London to Brighton. So we have the strange situation where the length of the race often exceeds the weekly mileage.’

When he turns his eye on marathon runners generally he feels that many get nowhere near their potential. ‘If you are covering 80/100 miles per week, the way to improve your performance is to build in more contrasts in terms of fast/slow, long/short runs rather than run all the miles faster or try to increase your mileage. Of course you must be psychologically prepared to live with much reduced mileages …’

In the ‘Athletics Alma’ quoted above it was said that he ‘trains hard on cigars and whisky and the three w’s.’ None of my informants believes that one. As far as The Diet is concerned, his thoughts are that it definitely helped him in longer races such as the Two Bridges and the London – Brighton although for the marathon itself, the risk of the physical upsets plus the depressingly poor runs immediately prior to the race more than offset the negligible gains.

Described by one of his great rivals as ‘always cheerful and talkative before and after a race but very tough in competition, he also has a fair (and maybe idiosyncratic) sense of humour. He has been seen after a particularly hard race pulling faces at a busload of competitors that would have won a gurning competition. Running with a young Donald Macgregor in the SAAA marathon, Don’s ESH team mates were shouting the boy on at about three miles. Alastair turned on the first time marathoner, smiled and said ‘Surely they don’t expect you to drop already? He went on to ‘break’ the boy at about 19 miles and win.

Alastair Wood is still not finished with the marathon – who would bet against a sub 2:20 marathon with his record? As one who has done a lot for the sport and who is not on record anywhere as indulging in any shady practices, as one who never took the money and ran, nor ran and took the money, he is a first class example for anyone taking up the sport. If he is not one already, he should be made an honorary member of the Scottish Marathon Club. Alastair Wood is a famous runner.

As I said that was written in 1983 and his thoughts on training could well form the subject for a week end seminar! “The invaluable practice of training every other day” would not go down well with many – but does it have merit? What is it? “If you are covering 80/100 mpw then the way to improve your performance is build in more contrasts to your training.” Discuss! A wonderful man who was maybe not appreciated as he might have been by the Scottish administration of the day and whose knowledge was shamefully under utilised.

********************************

Alastair Wood was of course more than a wonderful athlete he was a motivator and his influence on his fellow Aberdonians has already been mentioned. The following is an excerpt from an article in ‘Athletics Weekly’ by Ranjit Bhatia who knew and ran with him in 1959 and 1960.

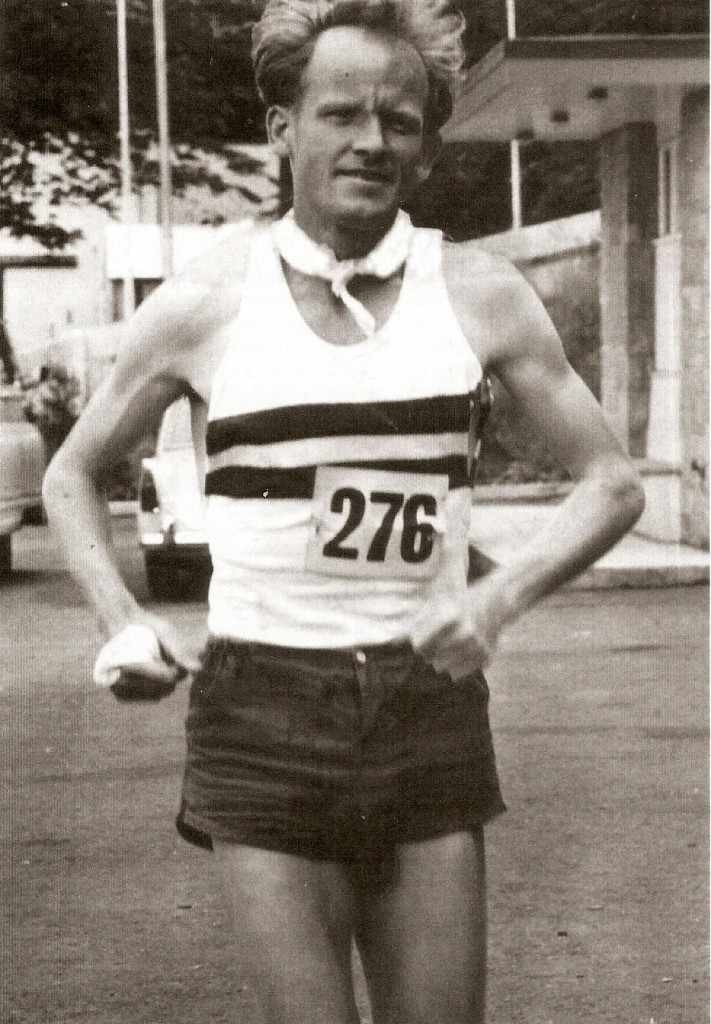

“The athletics career of Alastair Wood makes one of the most interesting stories of our time. I first met him in 1959 when he was serving with the RAF as a short service commission officer. He was keen to keep up his running while with the Air Force and fortunately enough was posted to Halton, a station which had a reputation for producing outstanding athletes. He was the only officer in the station athletics team and his amiable qualities made him very popular. During the winter of 1958 he proved to be their most outstanding cross country runner and it was not surprising to find him dominating the cross country events during the summer track season that followed.

Alastair left the Air Force the next year and joined Oxford University to do a post graduate course (he had graduated from Aberdeen University three years earlier). From October 1959 until the time I returned to India I did most of my training with him, and in the process learnt a great deal about distance running from this ‘elderly’ (born 1933) and somewhat eccentric Scotsman. He was much older than most of his contemporaries in the University Athletics Club and the three year stint in the RAF had left its mark on him. But then he was so very much an extrovert and within a few weeks he managed to build up a large following amongst the distance running fraternity at Iffley Road. But he and his wife Jean lived in a cottage nearly ten miles away from the centre and Alastair often ran to his lectures, and to the track for his afternoon work outs (“To save petrol”, he used to say). Every day around three o’clock one would hear his characteristic call. “Any of you clots here to train? Come on you lazy English! And you there from Poonah!”

A training session with the Aberdonian was a unique experience. He cursed everyone as he ran. If someone attampted to slow down the pace, Wood was there to male sure that he went even harder. By the end of the winter, Alastair Wood’s running group had acquired quite a reputation for themselves. They won practically every team race in which they participated. Came the 1960 International Cross Country Championships and no less than four of the seven members of the university cross country team won their International vests with Wood finishing seventh.

(This 1970 article goes on to mention Alastair’s track exploits and his switch to the marathon. It finishes with the statement: “He continues to be Scotland’s most colourful distance runner.”)

*****************************

In the January 1987 issue of the ‘Scotland’s Runner’ magazine there was an interview of Alistair by one of his proteges and running mates from Aberdeen – Mel Edwards. Mel is a quite outstanding athlete himself with many superb runs over the country, on road and track and also in the hills and freely admits that Wood was one of the inspirations behind his early career. In fact he won what is probably the best cross country race I have ever seen when he defeated Ian McCafferty at Hamilton in the Scottish Under 20 Championship. However we may speak of Mel separately at some stage but for now extracts from his article on Alastair are quoted here.

“Born in Elgin on January 13th, 1933, Wood went to Aberdeen University in 1954 and two years later won the Scottish Universities cross country title at St Andrew’s. He excelled at athletics in the RAF in the late Fifties and went on to take 16 Scottish titles (including eight marathons). His major Championship appearances were: 1958 Empire Games Three and ix Miles; 1962 European Championship marathon (fourth) and Empire Games marathon. Other highlights were a 2:13:45 marathon. a London to Brighton record and the World 40 Mile Track Record (1970).

Edwards: You’ve had a long career in the sport, Alastair. What are your most memorable performances?

Wood: Oddly enough the very early ones. Just about the first thing I won was the Scottish Universities Cross Country at St Andrews. I had to stop to tie a shoelace yet I still won by 300 yards. That was the first occasion I really though I was a runner. I went in for a mile race at Westerlands in summer 1955 with a personal best of 4:35 and found myself up against a couple of athletes who had been in Bannister’s first sub-four minute mile at Oxford the previous year. Looking back I should have been overawed by these guys but in the event I took off and was still leading after three laps. I was still in front with 100 yards to go and although I was passed I came down to 4:14 in that one race.

E: You went into the RAF for a short service in the late Fifties. serving at Halton which had a reputation for producing fine runners?

W: Yes, I won the RAF cross country championships in 1957 and this pleased me very much as Derek Ibbotson who broke the world one mile record that year had been a previous winner. The competition in England was invaluable. I came up to Meadowbank that summer to do the Scottish six miles a distance I’d never done on a track before. However with a 29 minute 10 second run including a 57 second last lap I managed to break Ian Binnie’s Scottish record by 0.8 seconds.

E: Moving on to the Sixties, I think I’m right in saying that this was the period you were really at your peak?

W: Yes, my fourth place in the European marathon in 1962 was a breakthrough in a competitive sense although not time-wise.

E: I remember doing my first two hour run in Aberdeen on the morning of that race so that I could watch you on TV in the afternoon with a clear conscience! But wasn’t 1966 an even more eventful year for you?

W: That’s right, the Commonwealth Games were in Kingston, Jamaica and I went for marathon selection. The only trouble was that I couldn’t get any guidance on the selection procedure. The Scottish championships were at Westerlands in early June and I asked John Anderson – who was the National coach and advising me on my training – if he could ascertain whether this was the race on which selection was to be based. He couldn’t find anyone who could tell him but suggested that if the winner of the race was to be selected then I had to do it. Anyway I was in excellent shape and travelled to Glasgow. It was extremely hot and the tar was running on Great Western Road. No one would confirm that the winner would gain selection so as the times were going to be slow I didn’t run as it would have done my chances of selection no good.

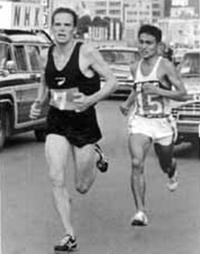

E: The Polytechnic Marathon from Windsor to Chiswick was two weeks later and Jim Alder and yourself went for selection in that one?

W: Yes, Again it was very hot but at least I knew that if I beat Jim I would almost certainly be picked. We both suffered and Jim finished fifth and I was two minutes behind in eighth. Jim deservedly gained selection and I was very ill with dehydration. I was pretty demoralised and decided to retire. This lasted all of ten days and although I couldn’t face long runs I got stuck into sessions 60 x 200 metres.

About three weeks after the Poly I went North for the Inverness – Forres Marathon. It was a cool day and I felt so good that I knew I was on a blinder. I reached ten miles in under 50 minutes and then slowed deliberately because I thought I’d blown it. I still came home in 2:13:45, a European record. There was considerable disbelief about the time but the course had been measured by surveyors and the North of Scotland AAA. Anyway, the next year the course started 200 yards or so back from the previous starting line, and although I found this one much harder I still did 2:13:45.

E: What are your views on marathon selection as a result of these experiences?

W: Basically the system should be objective enough to almost dispense with selection. Have a rule and stick to it. The American system in Track and Field of ‘First three’ in the trials might be ruthless but everyone knows what they have to do.

E: Going on to training now, you’ve experimented with virtually every form there is. Have you come to any conclusions?

W: There is definitely a lot to be learned from trial and error. Obviously if there is a perfect system it is the one which produces the most good runners, but some top class runners may have been even better on a different system. However, in a nutshell, training fast helps you to run fast. I don’t believe in the ‘something for nothing’ school of thought and reckon that interval training makes you faster than any other system.

E: But it’s not just training of the body, is it? I don’t think it’s far off the mark to say that you would psych yourself up for a race and that a lot of your best runs were through guts and a desire to do well.

W: A fair point. There’s no point in throwing the race away mentally before you’ve started.

E: What were your preparations for the London to Brighton and world 40 mile records in 1970?

W: I trained only every other day and never more than 15 miles at any one time. In a sense you could say that I did get ‘something for nothing’ with these two events because I wasn’t doing excessive mileage. The London to Brighton in five hours eleven minutes was ten minutes faster than the previous year and I remember after the 40 miles record a guy from Capital Radio asking if I could improve on my time next year. My comment on the likelihood of anyone being stupid enough to tackle it twice was not broadcast.”

There is more to the article than that and if you can get hold of a copy then it is worth reading. Mel has done a good job and I was relieved to see that he had been given the same replies as I had where the same questions were raise – but he has more colour in his interview and asked some questions that are more insightful than some of mine.

Alastair’s record breaking run in the London to Brighton was mentioned in the interview and I would like to include this excerpt from an article by Bill Brown in The Road Runners Club Newsletter of January 1973 which I received from Colin Youngson.

“The weather now became even gloomier with patchy fog at Gatwick. This could not have been very pleasant for the runners but it had little effect on the leaders who arrived at Crawley (thirty and three quarter miles)in the very fast time of 2:54:54, more than five minutes inside the record.. The leaders were Alastair Wood and Mick Orton with Cavin Woodward, two minutes slower, third. Both Hensman and MacIntosh, fourth and fifth, were running faster than the previous best and Houk, sixth in 3:02, was only a few seconds slower. Shortly after Crawley, Wood began to take charge of the race and soon opened up a large gap on the gallant Orton. When Wood reached Bolney, nearly 39 miles from Big Ben, in 3 hours 43 minutes 30 seconds he was a good 9 minutes ahead of Orton who had a three minute lead on Woodward. As usual there was now the customary speculation as to whether or not Wood was travelling too fast, and perhaps might not last the full distance.

The opinion of the two former winners, Tom Richards (1955) and Bill Kelly (1954) was that there was no doubt that Wood was just the sort of runner to conquer the distance and the record. Not even the famous Dale Hill seemed to have any effect on this talented runner, and so at Pycombe (46 miles) Wood’s time of 4:27:12 was no less than 10 minutes 48 seconds faster than Levick’s 1971 time. More than six minutes passed before Orton passed this check, yet he too was four and a half minutes better than the record.

So on to the Aquarium Brighton, where after fifty two and three quarter miles Alastair Wood was timed in with the incredible time of five hours eleven minutes and two seconds to smash the record by ten minutes 43 seconds giving Scotland a win in this event for the first time. The true worth of this time can be seen when it is realised that with an even time run at 10 mph (six minute miles) the journey would have taken five hours fifteen minutes. Yet when I spoke to Alastair Wood afterwards he stated that he had had no feelings in his legs for the last twenty miles. Congratulations on a magnificent run. So far was he inside the record that the Mayor of Brighton did not get to the finish in time to welcome him in. A good deal of sympathy must go to the rest of the runners. Especially to Mick Orton ho ran a splendid race in a brilliant time (5:18:28) to be content with second place.”

Alastair Wood – Marathon Career Record

| No |

Date |

Venue |

Position |

Time |

Winner (Club) Time |

| 1 |

23 June 1962 |

Edinburgh (SAAA) |

1 |

2:24:58 |

CHAMPIONSHIP RECORD |

| 2 |

11 August 1962 |

Welwyn Garden (AAA) |

2 |

2:26:35 |

Brian Kilby (Coventry Godiva) 2:26:15 |

| 3 |

16 September 1962 |

Belgrade (SER-Euro) |

4 |

2:25:58 |

Brian Kilby (Great Britain) 2:23:19 |

| 4 |

29 November 1962 |

Perth (AUS – Comm) |

DNF |

|

Brian Kilby (England) 2:21:17 |

| 5 |

18 May 1963 |

Shettleston |

1 |

2:25:50 |

|

| 6 |

15 June 1963 |

Windsor – Chiswick |

DNF |

|

Buddy Edelen (USA) 2:14:28 WR |

| 7 |

16 May 1964 |

Shettleston |

1 |

2:23:16 |

|

| 8 |

27 June 1964 |

Edinburgh (SAAA) |

1 |

2:24:00 |

CHAMPIONSHIP RECORD |

| 9 |

15 May 1965 |

Shettleston |

2 |

2:19:03 |

Fergus Murray (Edinburgh Univ) 2:18:30 |

| 10 |

12 June 1965 |

Dumbarton (SAAA) |

1 |

2:20:46 |

CHAMPIONSHIP RECORD |

| 11 |

10 July 1965 |

Inverness-Forres |

1 |

2:29:54 |

|

| 12 |

21 August 1965 |

Port Talbot (AAA) |

4 |

2:22:54 |

Bill Adcocks (Coventry Godiva) 2:16:50 |

| 13 |

03 October 1965 |

Kosice (SVK) |

5 |

2:29:59 |

Aurele Vandendriessche (BEL) 2:23:47 |

| 14 |

23 April 1966 |

Shettleston |

1 |

2:24:00 |

|

| 15 |

11 June 1966 |

Windsor – Chiswick |

9 |

2:28:29 |

Graham Taylor (Cambridge) 2:19:04 |

| 16 |

09 July 1966 |

Inverness-Forres |

1 |

2:13:45 |

|

| 17 |

13 May 1967 |

Shettleston |

1 |

2:23:02 |

|

| 18 |

24 June 1967 |

Grangemouth (SAAA) |

1 |

2:21:26 |

|

| 19 |

08 July 1967 |

Inverness-Forres |

1 |

2:16:16 |

|

| 20 |

26 August 1967 |

Nuneaton (AAA) |

2 |

2:16:21 |

Jim Alder (Morpeth) 2:16:08 |

| 21 |

11 May 1968 |

Shettleston |

1 |

2:25:27 |

|

| 22 |

22 June 1968 |

Grangemouth (SAAA) |

1 |

2:21:18 |

|

| 23 |

27 July 1968 |

Cwmbran (AAA) |

6 |

2:20:29 |

Tim Johnston (Portsmouth) 2:15:26 |

| 24 |

12 July 1969 |

Inverness-Forres |

1 |

2:27:44 |

|

| 25 |

25 October 1969 |

Harlow |

1 |

2:19:15 |

|

| 26 |

10 May 1970 |

Chemnitz (E.GER) |

DNF |

|

Jurgen Busch (East Germany) 2:14:42 |

| 27 |

16 May 1970 |

Edinburgh (SAAA) |

5 |

2:19:17 |

Jim Alder (Morpeth) 2:17:11 |

| 28 |

13 June 1970 |

Chiswick |

6 |

2:22:12 |

Don Faircloth (Croydon) 2:18:15 |

| 29 |

04 July 1970 |

Inverness-Forres |

1 |

2:13:44 |

|

| 30 |

23 August 1970 |

Toronto (CAN) |

2 |

2:18:32 |

Jack Foster (NZ) 2:16:24 |

| 31 |

24 October 1970 |

Harlow |

1 |

2:17:59 |

|

| 32 |

13 June 1971 |

Manchester Maxol |

8 |

2:16:06 |

Ron Hill (Bolton) 2:12:39 |

| 33 |

04 June 1972 |

Manchester Maxol |

20 |

2:19:00 |

Lutz Philipp (West Germany) 2:12:50 |

| 34 |

24 June 1972 |

Edinburgh (SAAA) |

1 |

2:21:02 |

|

| 35 |

23 June 1973 |

Edinburgh (SAAA) |

DNF |

|

Don MacGregor (Fife) 2:17:50 |

| 36 |

07 July 1973 |

Inverness-Forres |

1 |

2:22:29 |

|

| 37 |

19 May 1974 |

Draveil (FRA-World Vets) |

1 |

2:28:40 |

WORLD VETERAN CHAMPION |

| 38 |

01 December 1974 |

Barnsley |

2 |

2:26:15 |

John Newsome (Wakefield) 2:24:25 |

| 39 |

28 June 1975 |

Edinburgh (SAAA) |

3 |

2:21:14 |

Colin Youngson (Edinburgh SH) 2:16:50 |

| 40 |

15 August 1976 |

Coventry (World Vets) |

4 |

2:28:34 |

Eric Austin (Worcester) 2:20:51 |

| 41 |

23 September 1978 |

Viareggio (ITA-World Vets) |

5 |

2:31:12 |

Gianpaolo Pavanello (ITA) 2:27:31 |

| 42 |

26 May 1979 |

Edinburgh (SAAA) |

12 |

2:34:06 |

Alastair MacFarlane (Springburn) 2:18:03 |

| 43 |

16 September 1979 |

Aberdeen |

10 |

2:35:47 |

Graham Laing (Aberdeen) 2:21:40 |

| 44 |

24 August 1980 |

Glasgow (World Vets) |

15 |

2:28:35 |

Don MacGregor (Fife) 2:19:23 |

| 45 |

27 September 1981 |

Aberdeen |

16 |

2:36:20 |

Max Coleby (England) 2:21:29 |

| 46 |

09 May 1982 |

London |

249 |

2:33:35 |

Hugh Jones (Ranelagh) 2:09:24 |

| 47 |

15 August 1982 |

Elgin |

2 |

2:35:02 |

Don Ritchie (Forres) 2:29:36 |

| 48 |

19 September 1982 |

Aberdeen |

25 |

2:36:59 |

Gerry Helme (England) 2:15:16 |

| 49 |

14 August 1983 |

Elgin |

2 |

2:39:33 |

Don Ritchie (Forres) 2:36:11 |

| 50 |

18 September 1983 |

Aberdeen |

13 |

2:31:48 |

Kevin Johnson (England) 2:19:01 |

| 51 |

13 May 1984 |

London (AAA) |

|

2:33:32 |

Charlie Spedding (Gateshead) 2:09:57 |

| 52 |

12 August 1984 |

Elgin |

3 |

2:39:00 |

Don Ritchie (Forres) 2:29:17 |

Alastair Wood – Ultra Career Record

| No |

Date |

Venue |

Pos |

Time |

Winner (Club) Time |

| 1 |

23 August 1969 |

Two Bridges 36.2m |

1 |

3:27:28 |

|

| 2 |

13 December 1969 |

Pitreavie Track 40 miles |

1 |

3:49:49 |

|

| 3 |

19 August 1972 |

Two Bridges 36.2m |

3 |

3:25:49 |

Alex Wight (Edinburgh AC) 3:24:07 |

| 4 |

01 October 1972 |

London – Brighton 52.7m |

1 |

5:11:02 |

|

| 5 |

01 June 1973 |

Comrades 88.2 km (down) |

DNF |

|

Dave Levick (RSA) 5:39:09 |

| 6 |

24 August 1974 |

Two Bridges 36.2m |

3 |

3:32:43 |

Jim Wight (Edinburgh AC) 3:26:31 |

| 7 |

12 April 1975 |

Two Oceans (RSA) 56 km |

2 |

3:24:36 |

Derek Preiss (RSA) 3:22:01 |

We finish with a tribute to Alastair from his friend and fellow Aberdeen AAC runner Colin Youngson.

A Tribute To Alastair Wood

To me, Alastair was the runner hero, the inspiration, the adviser, the irrepressible outspoken character and the most stimulating of friends. He may have been easily bored but he was never boring. I knew him for thirty six years – certainly not long enough. Very shortly after meeting him, I recognised that Alastair was rather unlikely to compliment anyone unless they really deserved it. Many people were influenced by him, competed with him, admired him, suffered the lash of his sardonic tongue, learned simply to insult him right back, laughed with him and were glad to count him a friend.

Alastair Wood, along with Steve Taylor, inspired so many successful distance runners for over twenty years. This was mainly by example. When Alastair Neaves approached Wood, mentioned that he hoped to switch from football to running and asked him for his advice, the reply was “Running is ten times harder than football. Do yourself a favour – give up before you start – go to the pictures instead.” Of course Ally Neaves accepted the implied challenge and started training in earnest. I remember struggling to hang on to the pack during the Sunday fifteen mile run, which started from Woodie’s house. Some days the pace was so fast that I was left behind before Hazlehead roundabout. With perseverance my stamina increased and it was the same for so many others. What a combination Wood and Taylor were. Even after I could eventually defeat them in cross country, they could both run away from me on Sundays.

What images stay with me? Alastair Wood’s confidence; his tactical brain; that little half smile as he sped to fastest time on stage two of the 1968 Edinburgh to Glasgow relay. His beautifully balanced economical style which was just perfect for the marathon. Alastair winning the 1967 Scottish marathon title in Grangemouth, easing round the track, strolling to the track entrance, bantering with officials, sipping a cup of tea, and then applauding his protege, young Donald Ritchie who eventually came into the stadium to claim the silver medal. During the final John O’Groats to Land’s End relay twenty years ago Woodie, the oldest runner, battled so hard to ensure that his Aberdeen A.C. team would break the record again. It was tough, but so was he. This might explain when, on one occasion as Donald and I took over from him and Mike Murray, since he thought erroneously that we were late, Mr Wood threatened me with a particularly nasty personal operation if the tardiness were repeated. I ran away rather fast.

When he became ill, Alastair remained brave and uncomplaining, apart from the time, while he was recovering from the kidney operation, Steve and I made him laugh so much he was in agony from his stitches.

Only a few days ago , at Hogmanay 2002, I was lucky to spend an hour with Alastair. We chatted about many topics – people, books, cricket, cycling and of course running. He claimed cheerfully to be making a comeback and mentioned his plans for some rather dangerous speed training. I mentioned that he was definitely to be included in a forthcoming book about Scotland’s greatest athletes. He said this was just as well. If he had been missed out, the author Colin Shields would have received a sharp letter of protest. But although he knew his own worth, he was a modest man. Fraser Clyne wrote accurately and well about Alastair’s achievements in the Press and Journal – although Woodie might have remarked that he missed out the double blue for Athletics and Cross Country at Oxford; and the ultra distance racing in South Africa. I once suggested to Alastair that he had been a great runner; no, he replied, just a good one. Very, very good in my opinion.

One of my favourite books features many fleet-footed athletes. Its title is ‘Watership Down’. When a rabbit dies, the others say ‘one of our friends has stopped running today. Alastair finished his final session last Thursday. I’m not surprised he pushed it a little too hard. I will miss him a great deal. He was an unforgettable person: a great man.

Alastair Wood’s Two Finest Races 1966: Two Controversies involving Alastair Wood