A wonderful picture taken immediately after the war at Mountblow: just look at the happiness and joy in all the faces of this impromptu group.

The flash at the bottom only adds to the spontaneity of the moment!

This section is called ‘Typicals’ because it is easier to describe a typical event of its kind than to attempt to recount a decade in any sensible or accurate fashion if I am trying to describe the various aspects as they appeared to a total newcomer. The list is easy enough: A typical training night from the ‘Baths’; A typical inter club meeting; A typical winter race meeting; A typical summer training night at the ‘Recce’; A typical summer inter club meeting; A typical highland games competition. And anything else that comes into my head!

A typical training night in winter took place from Bruce Street Baths, or in Clydebank parlance ‘the New Baths’. The ‘Old Baths’ were in the adjoining street (Hall Street) across from the Police Station and the club had formerly trained from there in winter. The Baths were the Public Swimming Baths although they also had private baths and showers, Turkish baths and best of all from our point of view, there were two large halls downstairs with adjoining showers. The Harriers had the use of one of the halls for stripping purposes and it was the winter headquarters. When I first went along after taking up the sport doing National Service between 1956 and 1958, I didn’t know what to expect. I went with a friend down to the Baths, went in the main door and paid my three pence. I was asked if I wanted a towel (they could be hired for a penny) and then went past the entry to the swimming pool and turned right down some stairs to the stone floored basement. The bank of showers was on the left but we went to the right for about forty or fifty yards before turning right again into a large wide brightly lit hall with coat hooks around three walls. On the wall in the left was the notice board, in the corner on the right was a table (used for the occasional massage) and all round the room just below ceiling height were two hot pipes. The older guys hung their towels over them when they went out so that they had warm towels for the showers. There were guys of all ages from Under 15 to over 60 sitting, standing, jogging about, doing exercises (high knees was a favourite), blethering or just getting changed. There was no modesty about that either, folk just stripped off and then put on their running gear with the odd pause in the proceedings to exchange a bit of gossip or complain about the current injury. On the door was the note of ‘Tonight’s Trail’ which had been put up by the club captain. The route and distance were marked and departure times for the various packs listed. The slow pack left at 7.00 pm – that was a given. The slow pack always left at seven o’clock. The medium pack – usually the biggest – went next, and the fast pack – usually the smallest! – was last to leave the premises. Not everyone did the pack run but most did relying on the judgment of the captain to get the training right. Some did their own thing and went for a run on their own but there was always someone left in the Baths – maybe someone carrying an injury doing a bit of light training, maybe a former member down for the warmth, the company and the memories.

On the first night, I was asked what pack I wanted to run in but, not having a clue, opted for the slow pack. The run went by comfortably enough but I was slagged off a lot for going with the slows when I was clearly (to their eyes) better off in a quicker group. So for most of the first year I went with the mediums gradually picking up information about the club and experience of running in the club. On the return from the run, it was everybody stripped, towel over the shoulder or round the waist and wander the forty yards or so along the corridor to the showers. The showers helped make the Baths what were described to me as the best winter accommodation in Scotland – not by a club member but by a member of Dundee Hawkhill Harriers who came to the venue for the Balloch – Clydebank Road Race every year. In the showers once the jostling for position was over the ‘Clydesdale Choir’ started up. With Pat, Frank, and company in full voice all the Scottish tramping songs were belted out with gusto and everyone who knew the words joined in. Meanwhile Cyril soaped his vest and shorts and tramped them into a state of cleanliness! It was a fantastic end to the night’s exertions.

After one night I was totally hooked on all this and couldn’t wait until the next session on the Thursday. Most guys these days in all clubs turn up already changed, run, get back into their car and go home again. I can’t help thinking

“They’re not so good as they used to be in OUR young day!”

A typical inter club run in winter started with the guys meeting up on the Saturday outside Bruce Street Baths at about 12 noon. Inter club runs were basically pack runs with another club or clubs. At a time when there were not too many races on the calendar and the cost and difficulty of transport had to be taken into account before travelling to a race in Dundee or wherever, inter club runs added variety into the training, increased our circle of running friends and there was also a wee bit of competition in these friendlies. Our usual inter clubs – held on a home and away basis – were with Springburn Harriers, Greenock Glenpark Harriers, Vale of Leven AC, Garscube Harriers and Victoria Park Harriers (the second was usually at Milngavie with VPAAC and Garscube on the Saturday before the National Championships). We also had the occasional inter club with Dumbarton AAC and there were others with Forth Valley and Shettleston.

We would meet, those with cars would bring them, the runners would be allocated to a car and the procession would set off. For the Glenpark outing the procession would go over the Erskine Ferry at the start. It was on one of these in the 60’s that we were told that Ian Donald of Shettleston Harriers, who had been training with us for some months and living in Old Kilpatrick, had handed in a club membership application form. It started the afternoon off on a good note as he was one of the very best and already well liked in the club. The journey to the Orangefield Pavilion was full of anticipation of the coming run – at Greenock they usually took us up over the Lyle Hill and past the Free French monument – and memories of past meetings. Once there, it was get changed look at the ‘opposition’ and decide which pack would be the right one. The packs would set off and after the massive climb to the monument and back down to the main road the last mile or so was a bit of a race to the showers. Back in, shower and then there was the ‘purvey’ to be attacked. At inter clubs, there was always a cup of tea, a burnt sausage roll and a sandwich plus some cakes which were usually home baked and invariably had a collection of Empire biscuits included. All inter club runs were different, for instance:

- At Greenock, they were served up at tables for four with table cloths on the tables. This never happened anywhere else and made the trip a wee bit special. The run itself whatever course it followed always included a run up to the Free French Monument on Lyle Hill;

- Springburn Harriers hut, for instance, had a big plunge bath that everyone shared, and the trail usually went out round the Gadloch at Lenzie;

- The Vale of Leven AC clubhouse had showers that didn’t always work (more of a fine mist that descended rather than actual water) and it often came down to a scrub down in the freezing cold Murroch Burn. This made the trip a wee bit special!

- The run with Victoria Park was held from the Milngavie Community Centre. It was always the week before the National Championships. (Incidentally, the practice then was not to issue race permits for the week before the Nationals or for the week end of the event. Now permits are issued not only for the week prior but even for the day after the National Championships itself which to me is a disgrace.) The run itself was over four golf courses and was a three club affair with Garscube Harriers being the third squad.

Further back, the ‘Clydebank Press’ tells of one occasion in the 1930’s when the club had an outing to Garscube Harriers hut at Westerton and many workers had been laid off in John Brown’s Shipyard and work halted on the Queen Mary, the rain was pouring down and the runners had to walk to Garscube. Out came Tommy Arthur’s mouth organ and they san songs all the way to the venue – one of the songs was to the tune of ‘John Brown’s Body’ and went:

John Brown’s Cunarder lies a-mouldering in the stocks,

John Brown’s Cunarder lies a-mouldering in the stocks,

John Brown’s Cunarder lies a-mouldering in the stocks,

While we go unemployed.”

They arrived, ran, got dressed in the wet clothes and walked back home again. But they enjoyed the inter clubs in their day as much as we did in ours. In many ways it is a pity that there are so many races now with so little opportunity for socialising and doing runs just for fun.

Home inter clubs started a week beforehand with arrangements being made for the ‘purvey’ and the trail being confirmed. The inter club was an event where hospitality was extended to the visitors and that meant tea, sausage rolls or pies, maybe some sandwiches and buns and there were always cakes! Either home made Empire biscuits or fairy cakes or even boxes of four or six fancy cakes from one of the local bakers. The sandwiches and buns were normally baked at home by the wives of members who also made the tea on the Saturday and served it in the basement of the Baths. The trail for the run was decided by the club captain and on the day three, or at times four, packs would leave at intervals. Each pack had a pace at the front and a Whip at the back. The pace had to do just that – set the pace of the pack and know the exact trail being used. The others in the pack had to remain at least two yards back and not force the speed of the pack. The Whip at the back had to keep an eye on the pack and keep it together. If any member was suffering too much or dropping too far behind the pack, then the Whip had to communicate this to the pace who would slow down a bit. In the beginning the club whip used a hunting horn to communicate with the pace. The theory was that all packs would arrive at the Baths at the same time and by and large that was what happened. Everybody showered and while they were doing that the women were upstairs getting the tea organised. No choice of tea, coffee or whatever: it was tea. The sausage rolls and pies were warmed up and by the time that was ready, the runners were ready for it as well. It was a fine social occasion and many friendships were made or cemented at these gatherings which were exclusively male and almost exclusively adult. If there were any sandwiches or cakes left over they were sold for club funds.

Good runners in their droves came from such training and runs – on one occasion Mike Ryan of St Modan’s in Stirling came along to the Baths for an interclub run with us and enjoyed the experience. He later emigrated to New Zealand and won a Bronze in the Olympic Marathon in their colours. The inter clubs took place every year and made and cemented friendships as well as providing continuity for all clubs for decades.

As far as racing was concerned there was a typical winter fixture list which started with the McAndrew Road Relay on the first Saturday in October at Scotstoun, followed a week later with the County Relays at whatever venue was hosting it this year – it went round the four member clubs of Vale of Leven, Garscube, Dumbarton and ourselves – and then the Midlands District Championship. That was all there was before the Edinburgh – Glasgow Relay on the third Sunday in November. Like most clubs we had a trial to select the team for the McAndrew over a course in Clydebank and the four or five four man teams would be selected by the five wise men of the selection committee. After the trial on the Tuesday before the race, the selections would be written out and pinned to the notice board inside the door at the baths. Usually the first four were the first team, the second four the second and so on but occasionally one of the top men would miss the trial for some reason such as having to work late and a decision would have to be taken about whether he would go in or not. For the County relays there were other problems – for instance Peter Ballance was a very good road runner who was often in the first team but not a good country runner so he would often have to give way to someone who had run less well in the McAndrew. Getting the team right for the Midlands was the important thing and both early races were used for that selection. On the day of the race, it was usually a matter of arranging a lift from one of the guys with a car and every attempt was made to get guys in the same team into the same car. And this was the pattern for most races over the country or on the roads between October and the end of the following February. The single exception was the Edinburgh – Glasgow eight stage road relay race.

The lead up to the race: From the McAndrew trial – and maybe before – the focus was on the Edinburgh-Glasgow Relay Race, also known as the ‘News of the World’ because it had been sponsored by that paper from its inception in the Thirties. And right well supported it was too with limousines supplied for the officials and nine buses for the runners which was one for each stage plus one that was used at the start of the event to take stragglers through to the start. The probable team was discussed at length on training runs, at inter club meetings, at committee meetings and in fact anywhere that two or more Harriers were gathered together. Soundings were taken from every possible team member about what leg he wanted to run. Then the trial was held over 5+ miles and the selection committee deliberated on who would be in the team and which stage they would run – with distances ranging from 7 miles for the longest (sixth) stage to 3 miles+ for the shortest (third) stage, with the road being flat at one point or undulating at others, with decisions about who had the temperament for the first stage and who could face the heavy traffic at the Glasgow end, it was difficult to please everybody but it was without doubt the big race of the winter. Only 20 teams would be selected to contest the race, medals were given to the first three clubs to finish and there was a special set for the team which in the opinion of the judges had produced the most meritorious unplaced performance. There was the additional incentive for the first two teams of a place in the London-Brighton against the winners of the other regional relays sponsored by the paper. The Southern London to Brighton was the biggest, with others in the Midlands, the South West, the North West and the North East. Sadly we were not concerned with this in my time – our concern was to make the race and to have a go at the most meritorious medals. We were invariably successful in the first, not so often successful in the second.

A typical Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay Race. Once the team was picked, the pressure on the team members was fairly intense. Having spoken of nothing else, with the results of every E-G race since 1930 on the club notice board and a special supporters bus hired to follow the team it couldn’t have been anything else. The News of the World had nine coaches leaving Cunningham Street in Glasgow fairly early in the morning – one for each stage and one which would leave a bit later for the stragglers. The theory was that each runner would go in the coach labelled for the appropriate stage of the race which would ensure that he got to the start in time for a warm up before the race. The reality was that we usually waited for the stragglers bus so that we knew Cyril O’Boyle had turned up! The buses travelled through to Edinburgh and lined up at the side of the road. There were several Bentley and Rolls Royce limousines for the officials there as well – all provided by ‘The News of the World’. Teams were declared and numbers collected and distributed. Those running further down the line had something to eat and drink while the first stage runners started their warm up.

Buses with second and third stage runners left for the start of the appropriate stages. Supporters cars, the club bus and members of other clubs were there asking how the team was doing, how particular runners would do, runners were finding out who the opposition was on their stage and generally the already high atmosphere became so tense that you could almost feel it in the air.

The race was invariably started by the Lord Provost of Edinburgh or his representative and a special baton containing a message to the Lord Provost of Glasgow given to the first runner of the winning team from the previous year. If the runner with the baton were passed then he had the baton exchanged for a normal one while the special one went to the leading runner. For individual runners the focus had to be on their own race. While they were trying to do that, their team mates, club supporters and others who had come along were stopping their cars and the team bus in lay byes, on grass verges, in farmers’ gates and even on pavements to shout their runners on. Often if there were a duel between two clubs the opposition would be out at every opportunity with the stop watch checking if the gap was growing or diminishing. Runners would finish their stage, put on their track suit from the selection in the official bus, transfer as soon as they could to join club members and do their share of shouting at team mates and a continuing analysis of their own run would be conducted for the length of the race with every club member they came across.

During the race, results were typed out and roneo-ed for distribution at the end of the succeeding stage – results from the first stage would be available at the end of the second and so on. Strangely enough this was not done latterly when computers and printers were available and they had to be collected at the presentation. After the race, there was an official meal and presentation for runners and team managers in the Ca D’Oro restaurant in Glasgow. When the NoW stopped sponsoring it, sponsorship was taken over by Barr’s Iron Brew and the post race meal was in Strathclyde University Staff Club organised by Alex Johnstone. Medals were awarded after the meal – gold, silver and bronze plus the big bonus for most clubs – the award to the most meritorious unplaced performance. This caused a lot of disagreement with the judges as does any subjective award of prizes. Then it was out into the streets of Glasgow and head for home.

The race was usually covered in some depth in both the ‘Glasgow Herald’ and ‘The Scotsman’ which always had a picture of the start across the whole width of the page above the report and of course the ‘Athletics Weekly’ also had a stage by stage report in which, if you were lucky you might even be mentioned individually.

A Typical National: The National Cross Country Championship was always held at Hamilton Race Course in the 50’s. Again we would travel down by bus – all ages this time and when I joined the club, they were all male. The women in the club at that time were all track and field athletes and in any case their championships were held separately. Runners, parents and supporters were all there and it was a day out as much as a serious race – in almost all respects the E-G was a bigger race – the only real difference (and it was a REAL difference) was that this was the National Championship of Scotland which the club had won fourteen times in the early days and it was treated with respect. Everyone who was anyone would be there – several of the better runners missed the E-G because their club wasn’t strong enough to be invited in, but nobody missed the National.

The course at Hamilton was a horrendous big kind of double button hook. The race started with a long downhill slope on the good grass of the actual race course before meeting the ends of the first button hook (a big loop!) where the climb seemed to be gradual at first but seemed to get steeper and the going seemed to get heavier up the long, long hill before starting to turn back and drop down to the bottom of the loop and join the main straight that had been downhill at the start. It was a seriously long uphill drag this time and by the time the start was reached nobody was really enjoying it. If they were, they weren’t trying! The trail went straight through the start and into a small buttonhook round to the left before coming back to the main stretch again. The Senior Men did three and a half or four laps here and it was a very difficult course to judge.

On the race day, the runners warmed up while the younger boys’ races were taking place and many supporters had brought binoculars with them because although the distances were great, there was nothing to obscure the view. After the race it was back into the bus, have a post mortem on the way home. And another post mortem on the Sunday run, and on the Tuesday and Thursday runs as well!

A typical training night at Mountblow Recreation Ground was totally different with people that hadn’t seen each other since last summer meeting and sharing a changing room again. Catching up on gossip, arranging teams for track inter club meetings and so on. The changing accommodation was in a 1930’s type pavilion with four dressing rooms, a shower room with three showers and three sinks on each of two floors. The men used the downstairs provision and the women were up stairs. Club equipment was kept in a large basement Boiler Room – smaller items in the Club Box and bigger items (eg high jump stands) parked wherever there was space. In charge were two groundsmen – Ben Ward was the top man with his colleague Charlie (I never found his surname) who had a cleft palate. Anything you wanted, they usually had it.

Outside the Pavilion were two grass football pitches, one on each side of the path, then the cricket square on the right and the track was red blaes round another football pitch. It was nearly four lanes and was 330 yards round. The jumping pits were between the path and the cricket square and the area was very adaptable. The perimeter was good flat grass and approximately half a mile round; there was a hill behind the pavilion that could be incorporated into laps or just used for hill reps. It was also possible to get a straight 300 yards on the grass if you wanted it. In the mid 60’s two pole vault pits were constructed with a tar run up between them enabling the vaulters to use the prevailing wind. The pits were filled with rubber off-cuts from the Dunlop factory which were stored in the Boiler Room when not in use. Everywhere you looked there were athletes – men and women, boys and girls– running on the track, doing reps round the perimeter, throwing the javelin or putting the shot or even high jumping or pole vaulting. Were the club to have a single venue again the scene would not be much different today.

Much of the equipment was by the inadvertent courtesy of the Singer factory – starting blocks for instance were manufactured locally. That which any athlete needed was readily produced by the club. I remember Ian Logie looking for one of the new fibre glass vaulting poles and by SAAA Regulation we could not buy one for him. A Committee Meeting was held at Mountblow and the decision was that the club buy a pole for club use and that Ian was to be the club custodian of the pole!

Almost everyone walked to the track and walked home. However they came, the conversation and fellowship was one of the main attractions of the Harriers. This social dimension is one of the aspects of the club which is absent at present largely because of the prevalence of the car as the favoured mode of transport..

Ithe twenty first century athletes are very conscious of what gear to wear for every conceivable climatic condition and also of the possibility of obtaining a sponsorship contract from one of the major athletics clothing suppliers. It is a fair question to ask what the typical runner of the Fifties wore – what was available and how it was modified or added to.

So what did the typical Harrier wear for training and racing? The advice was to have three tops and three pairs of shorts – one on, one in the wash and one to wear tomorrow. Of the tops one had to be club uniform. The uniform was worn much more than today for training purposes: possibly because there was much less in the way of athletics clothing for sale in the shops and possibly because there was more pride in the club vest. These were the days when T-Shirts had no writing on them and not many athletes were fortunate enough to have one. Plain athletics singlets were the most common form of top layer and they were often topped by a plain or patterned jersey – see the one George White is wearing in the picture below! Some athletes (including Victoria Park’s Andy Forbes) used to wear a single sheet of brown paper below the singlet or between the singlet and jersey on very cold nights. Shorts were slightly longer than at present and were square cut. Several clubs had the club shorts trimmed with a distinctive colour and the Clydesdale shorts were black trimmed with white braid. Shorts were part of the uniform and specified in the constitution of the club. Ankle socks of any colour and then the shoes! When I joined the club most runners trained in sandshoes or plimsolls or gutties – they were different words for the same thing: a thin layer of rubber topped by a thin layer of cloth. Fine and light, they helped you feel every stone on the road. Most road runners used them for racing purposes. Spikes were usually leather with the actual spikes part of a solid plate in the sole. Once the spikes were worn or damaged, the shoes had to be replaced. Very few runners had more than one pair of spikes at a time and the length of the spikes – well the length of the spikes was the same for cinder track and all conditions of cross country. There was no writing on them either. Makers included Foster’s, Walsh’s and Reebok with the Adidas and other foreign brands just coming into vogue. Walter Ross used to sell the Finnish ‘Hirvi’ shoes from the offices of his ‘The Scots Athlete’ offices in Glasgow – runners came from all over the UK for the Hirvi spikes whose spikes were made of copper. They wore out quickly but they were in demand by those who liked light and comfortable shoes. Many runners of course used Dunlop tennis shoes and anything else that was light and pliable enough to run in.

The famous Millington Track suit was also in the shops and what an item it was. Baggy and bulky made of wool with a cotton top layer – the wool to keep you warm and the cotton to keep the wool reasonably dry. You can see Peter Balance wearing one in the picture of him cheering on Pat Younger in the E-G. Not everyone had a track suit – you can see some Track suit tops in the picture above with a very proud George White wearing the full set.

Where did we get the equipment? There was a shop in Glasgow – Harris’s in Exchange Square as it said on the label – which kept stocks of all the club uniforms for Glasgow clubs. And the vests were made to last. I remember running behind a clubmate on a training run and noticing that the vest was so old that the black had turned to a lovely deep green colour, shiny and reminiscent of a rhododendron leaf in colour and texture. They were made of some heavy material with the huge black C made of felt and sewn on. When it got wet it became very heavy inducing a serious forward lean to the running action in the finishing straight on a wet afternoon. There was also Roberts’ Stores in the Trongate which sold athletics singlets, shorts, Millington track suits and a variety of shoes. It was so far from Central Station that going there almost counted as a training run in its own right.

It is a small group of runners taken at a Club Cross Country Championships at Braidfield Farm in the very late 50’s or early 60’s. On the left are John Maclachlan with sweater over his club vest and square shorts tucked up for more freedom of movement and Eric McMahon similarly clad; then comes Jimmy Young in a football jersey (another common item of dress) and club shorts trimmed with white; George White who had probably won the race in a Fair Isle kind of top over his running vest and black untrimmed shorts; David Bowman in a long sleeved jersey no doubt over a club vest because David always, always wore club uniform, and trimmed club shorts; Andrew McMillan properly dressed for the occasion with his cap on and Billy Hislop dressed as an official should on a cold afternoon with coat and scarf (probably worn over his suit) and real leather shoes on his feet. The young chap in the duffel coat was young Ian McMillan, Andy’s son. There is quite a range of outfits in this picture – and an absence of track suits which, if you had one, was being kept for bigger meetings.

And that was the gear – first and foremost club uniform, then anything that was suitable for the job in hand wherever you could lay hands on it. Days were changing fast though and Adidas was on the market with the Adidas ‘Rome’ shoes (leather road running or training shoes) becoming a big seller after the Rome Olympic Games and for some time thereafter. When the Tiger Shoe Company (now Asics) of Onitsuka, Japan produced their Tiger Cubs at £1:2:6 (£1:25 in today’s money) they were a revolution – good quality canvas shoes with a tight fit at the heel, a wider toe compartment and a thing but fairly good sole – and everybody wore them. To start with they had a label tied to the laces of every pair which said “These shoes is the fruit of the effort of the workers of the Tiger Shoe Company of Onitsuka, Japan”. That would be the start of the ready availability of mass produced quality athletics clothing and footwear.

Of course the point of the whole year was the competition and the results and trophy winners were celebrated at the Annual Presentation and Dinner Dance. The typical Presentation Social as it was known to some of the older members was always a very formal affair and organised well in advance. The venue was usually somewhere away from Clydebank which also added an element of distinction to it. Like wearing club uniform, like social evenings to the theatre or even the Edinburgh Tattoo, it was part of the emphasis on togetherness and club spirit. Alex Hylan remembers two in the late 40’s in particular: the first was at the Masonic Lodge near the old Caley Railway Bridge in Clydebank, just along from the foot of Kilbowie Road. Biscuits, cake and tea were served. The other was in Whitecrook at the old Orange Halls which had started life as John Brown’s canteen. These were just after the War and money was scarce. In my first few years in the club the presentation was held in the Balloch Hotel, the Blane Valley Hotel in Strathblane (now a housing development), the Kingsclere Hotel in Helensburgh (later the Commodore) and the Loch Lomond Hotel. A large bus (on one occasion two buses) was hired, the tickets were properly and professionally printed and sold for weeks in advance. They often cost about the £12 mark – a significant amount in these days – and no one complained about the cost. Young members of 15 and under who had won prizes could come for half price. All who could come, usually came. The formality was emphasised by having a top table with members of the club executive, their wives and partners and any guests. There was always at least one guest of honour to make the awards. These were well known sportsmen (Andy Forbes and his wife, Lachie Stewart in 1970 and others in between), local politicians (Jimmy Malcolm, Malcolm Turner and others), local school teachers who had contributed something to the club (Joyce Hume from Vale of Leven Academy, Jack Fearn from Braidfield High School) and former members whom the club felt should be honoured (Alex Cameron, Charlie Middler for example). The club trophies and other awards made a superb sight glittering on a side table which was large enough for them all to be seen to best advantage – many a guest of honour commented with surprise and admiration for the quality and quantity of silverware on display. The menu was always presented on a proper menu card and distributed round the tables – at the end of the meal, members would often collect signatures from fellow guests as a souvenir of the occasion.

The evening began with the bus run down to the chosen venue, the men all in lounge suits and the women in semi formal dresses and fancy jewellery and the atmosphere was always electric with anticipation. Some time in the bar or looking at the trophies then in to the tables. The top table all had their places marked on card but everyone else sat where they liked. The meal was enjoyed and then the presentation started. The President called the gathering to order and the speeches started. There weren’t many. The President welcomed the company and especially the Guest of Honour, the Guest of Honour made his contribution (some did it better than others) and then the prizes were awarded. Cross Country first to all age groups and then Track and Field to all age groups before the President thanked the Guest for his part in the presentation. The tables were cleared and then the dancing started. There was always something more or less spontaneous. For instance one year at the Loch Lomond Hotel someone asked for a rendition by the Baths Choir: Pat, Frank, Charlie, Eric, Allan and company needed no real encouragement to give us ‘The Road to the Isles’, ‘The Mingulay Boat Song’ and a variety of tramping songs which were all well received with others joining in to make a super sing-song. On another night, when Bobby Bell and his wife Lily were there after a long absence, they gave a demonstration of ballroom dancing – They were professional dancers.

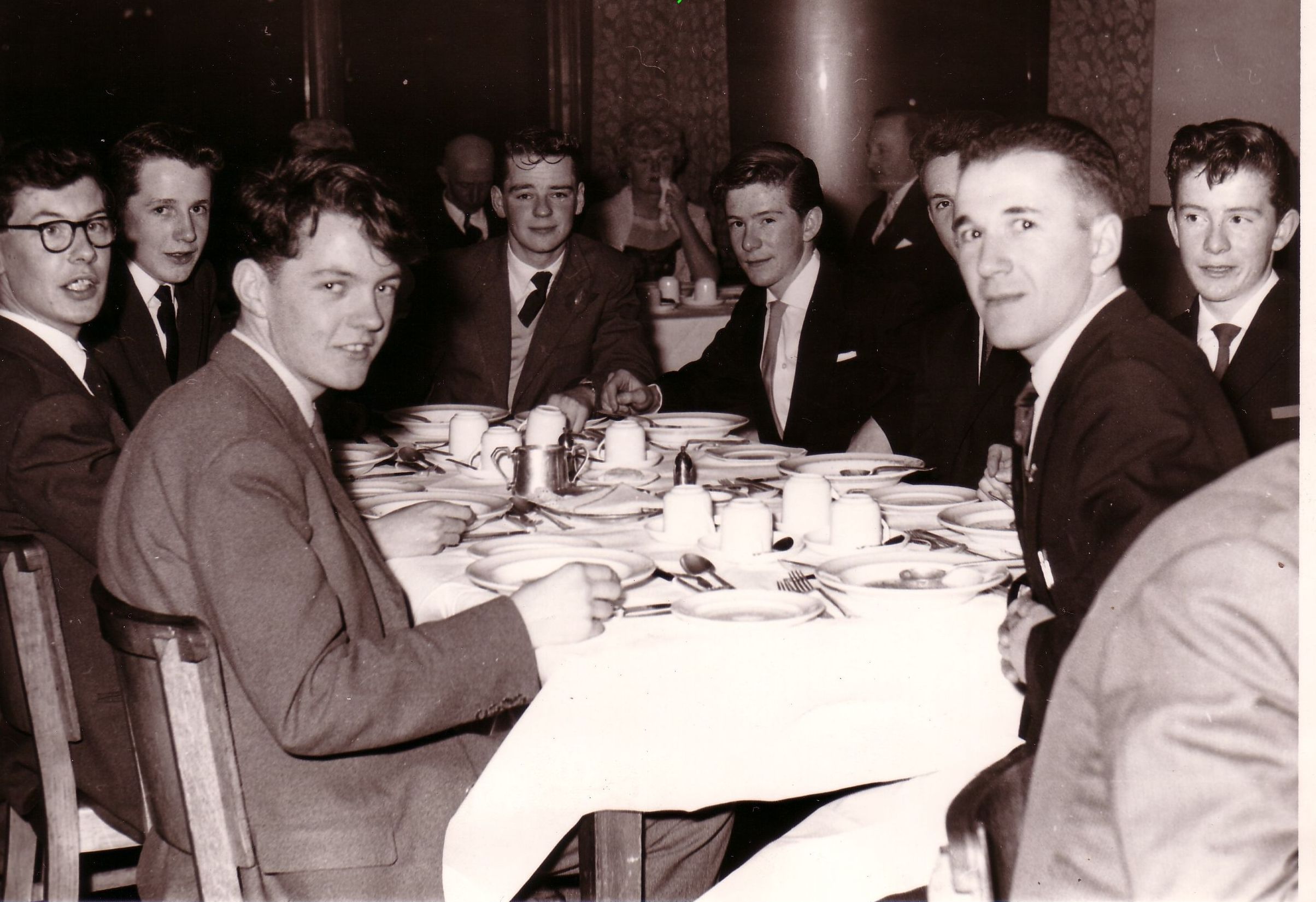

Presentation Group: Brian McAusland, Jim Crawford, Buster McCall, Malcolm Buchanan, Bobby Shields, John Maclachlan and Jim Shields

These were only some of the features of life in the Harriers when I started there in the 1950’s and many of the features that made athletics so magical and magnetic are no longer in existence. Some literally so (club headquarters such as the various Public Baths have been knocked down or transformed into Leisure Centres, cross-country trails have been built on in whole or in part and road courses have been altered because they are ‘too dangerous’. That has meant lots of traditions going. In addition society has changed, in some ways not for the better – eg club social life and bonding has to be artificially created where in former days we would walk to the headquarters, meeting other club members along the way, exchanging gossip, arranging future meetings, now most members just turn up on four wheels and go home on the same four wheels. As far as I can see the only ‘typical’ today is the four or five 10K road races every weekend!