I once walked through the streets of Springburn carrying two knives with 12″ blades, albeit that they were in a nice box. That’s one of them above. They were the first handicap prize from a 12 mile road race. Handicap prizes were not always appropriate. I was once chased through the streets of Helensburgh by a team mate after the 16 mile road race. There were four in the team, the first three were the scoring runners who had won the team race, and I won the first handicap prize. Their award was 6 coasters + 6 place mats with pictures of highland cattle up to their knees in water – mine was a Schreiber coffee table. Handicap prizes were not always distributed equably. For the team prize at another meeting we won fireside rugs (57″ x 25″ I think) and mine was given to a friend as a wedding present. Handicap prizes were sometimes useful. On another occasion I ran a 16 mile point to point, won a handicap prize that was a metal fire screen which I had to transport home on a bus. Handicap prizes were sometimes sources of puzzlement . . . or puzzlement.

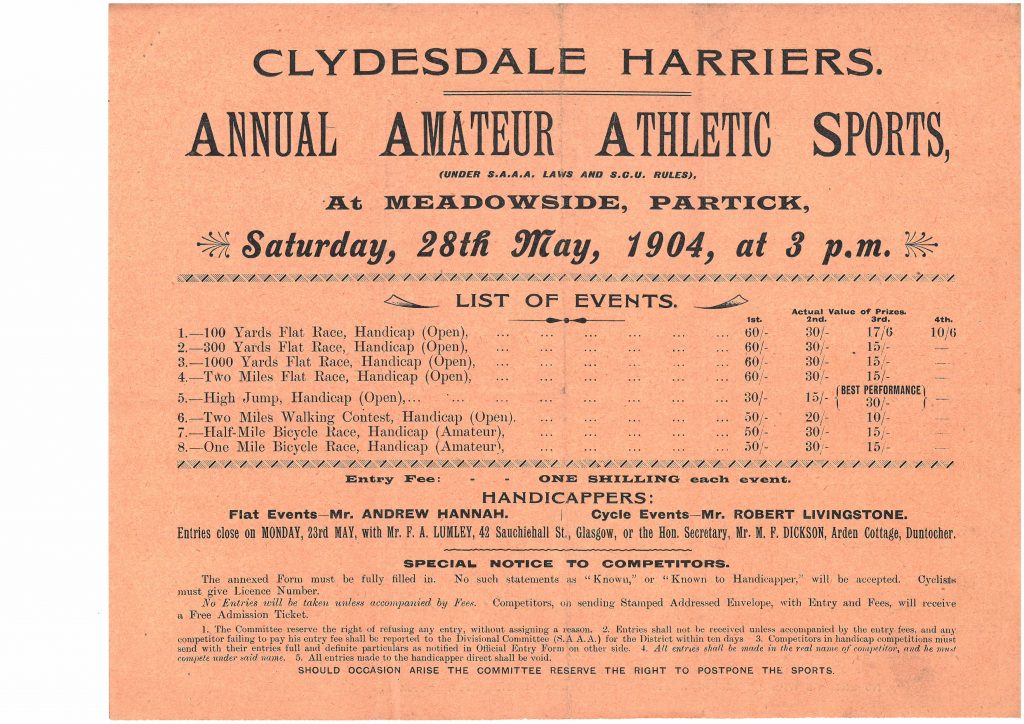

The races above were in the 1960’s and early 1970’s and in the amateur ranks subject to many rules. They were much less uniform across the country as far as the professionals were concerned – see Handicapping – SCOTTISH DISTANCE RUNNING HISTORY . The form below tells us that the practice was very well established in the ranks of the amateurs well over a century ago. Tom McNab’s look at the history of handicapping is below.

Handicaps . “ T. Cowburn will run any of the following men 100yards, R. Haworth, Manchester, if he will allow two yards start, or Oakes of Bolton, one yard in a hundred. Or Winstanley of Miles Plattin 120 yards, level. Any of the matches can be made at Crompton’s Rifleman, Hulme, for £5 or £10 a side.”

Thus Bell’s Life, September 8, 1861. The newspaper records fifty matches for September, but that probably represents only a small fraction of the foot-racing matches in that month, (most of them local), between men far short of championship class.

The culture of handicapping depended on betting, with the aim of dead heats, or certainly close races, something which scratch competitions rarely offered. It centred, as did pugilism, round public houses. The rapid growth of the railway system after the “Rocket” in 1825 meant that, even as early as 1861, local handicap-based match-racing would begin to decline, to be replaced by “Pedestrian Carnivals” in the major towns. Of these, Sheffield was the Blue Riband, to be replaced in the final quarter of the century by the Powderhall New Year Handicap .Twenty years later, Bells Life advertised no local match-races, though a handful still occurred, almost always between elite athletes, and mostly on a scratch basis. Match-racing ended in Scotland , in the early 1930s.

Corruption eventually killed Sheffield as a centre for professional handicap racing by the end of the 19th century. Not so Edinburgh’s Powderhall Handicap, which stood above all other meetings in the quality of its ethics. By this time, there had been the ghastly Hutchens-Gent fiasco at Lillie Bridge in 1884. There, no agreement on the winner having been previously reached, neither athlete ventured from his dressing-room, and an enraged crowd burnt down the Lillie Bridge stand. This sounded the death-knell for professional footracing in London.

So handicap professional athletics retreated to Scotland, Wales and the industrial north, though it lingered in the minefields of Kent and in occasional rural meetings in southern England.

Enter the amateurs, in the final quarter of the 19th century. Ignoring the fact that handicaps rested upon betting, they ruled over a network of mainly rural handicap meetings. This meant that it took till 1906 to remove bookies from amateur meetings, and the corruption that went with them.

A major problem which faced the amateurs was the question of prizes, for its administrators believed that men should compete for the joy of it, rather than for a prize. So at first the meet-organisers offered cups and medals, which the athletes firmly rejected. Next on offer from governing bodies was any prize upon which an EPNS plate could be riveted. Here the aim was probably to avoid the re-selling of prizes. This naturally limited the type of award which could be offered, and was almost equally unpopular. Finally, the blazerati caved in and offered straight prizes, usually a useless piece of bric a brac, thus obliquely preserving the ethic of sport for sport’s sake.

Which is where I come in, around 1950. I found that there was little competition in our Scottish handicap open meets for fifteen year olds, and all of it was in running events. And when senior status was secured, field events were rare, despite the fact that Scotland had bequeathed to the world most of its field events programme. And, lawdy lawdy, all field events were also on a handicap basis, something quite alien to the professional Highland Games whence they had derived. Handicaps ruled. Hell, we even had 120 yard hurdles handicaps, a nightmare to anyone who had any realistic aspirations in the event.

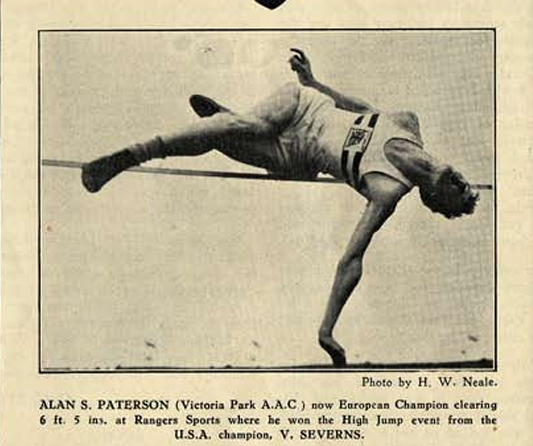

Thus it was that I was regularly given a 30cm. start on our great Scots high jumper Alan Paterson, and it shames me to admit that I never once defeated him. And later, when I was Scottish triple jump champion, I had to give away starts of over two metres.

The basic principle of the amateur handicap system was to hand out prizes to the mediocre, to retain them in the sport. And it was based on fixed penalties, ie a win in 100yards lost you 1.5 yards. But it went beyond that. I well remember winning prizes in one meet in shot put and high jump. As a result, my handicap in the sprint next week was immediately reduced by a yard, and my mark in half mile by 20 yards.

Handicapping in professional athletics was driven by betting, but in amateur athletics it was driven by the desire to evenly dole out prizes. In the races, it had the advantage of occasionally providing blanket finishes, but only rarely, because handicaps were not based on time, but on fixed penalties. The “blanket finish “ advantage did not, of course, apply to field events, where handicaps simply meant handing out prizes to athletes with big starts. And the prizes! Each meet-organiser seemed to have a friend in town who earned his living by selling junk. Thus it was that I returned to my mother many a summer Saturday with barometers, cake-dishes and cutlery. And woe betide any athlete who found out where that junk had come from, and took it to the shop to replace it for something which he actually wanted. For he immediately became a “professional”, as he did if he dared to sell his prize for filthy lucre.

So much for the history of handicaps, hardly an honourable one, one of corruption in professional athletics and the rewarding of the mediocre in the amateur sport. I have no objection to their occasional revival, as a curiosity, or for variety, though if we wish to operate with betting-odds and bookmakers, as did the old professionals, then buyer beware. And handicaps can undoubtedly be of great value with children. They have, however, no place at all in field events, and that is not because, fifty years ago, I had to give away two metre starts in triple jump!

The extreme was events such as the one retold to me by a very good Irish runner living in Glasgow in the second half of the 20th century. He and his wife or brothers would go on their bikes to what he called a “wee flapper meeting” out in the sticks, he wearing his work boots and long trousers. He’d approach the handicapper and ask if he could get a run, mister. He’d be looked up and down and told to start up there, the official pointing at a favourable mark. Off the runner went, removed his trousers, changed his shoes and won the race. He’d collect the prize at the run and they’d all take off on their bikes as fast as they could go. There are similar tales told in Powderhall & Pedestrianism: 1 – SCOTTISH DISTANCE RUNNING HISTORY about even quite famous runners such as the Irishman Tincler. It’s a subject that lends itself tales told.