Brian Gardner’s detailed, five-section memoir – ‘No Cross-Country for Old Men’ – is fascinating to read. Not only is it very well written but, with complete honesty and wry humour, it also traces the highs and lows of life (sporting and otherwise). Brian had considerable athletic talent, which was nurtured at Airdrie Harriers and Clyde Valley AAC, when he was coached by the great Tommy Boyle. Young Brian was especially good at 800m, 1500m and cross-country. He won a Scottish Schools Steeplechase title. Moving to England (for study and then work) Brian improved his personal bests and finished a very good 14th in the 1979 Scottish Senior National Cross-Country Championships. Sadly, injuries interrupted progress and led to depression. However, this is a tale of amazing resilience, recovery and achievement, against the odds. Even after his tenth operation meant complete retirement from running before the age of 60, Brian switched to competing in Open Water Swimming. (Earlier, he had also won a British title in the sport of Modern Triathlon (Swimming, Shooting, Running).

Section Four, below, deals with Brian’s stellar running career as a Veteran athlete (M40 to M55). Read and enjoy!

(As paperback, hardback or e-book/Kindle, the whole book is now available to buy from amazon.co.uk Just type in ‘No Cross Country for Old Men by Brian Gardner’.)

No Cross-Country for Old Men

By Brian Gardner

The Closing Laps: Veteris

Chapter Fourteen: Crisis

The summer of 1993 was disrupted by another operation, although not for a sports injury: it was a vasectomy. Recovery was supposed to be easy but, thanks to an infection, it was more painful than the last two operations put together.

Going into the biathlon season, I was swimming more often than running. The climax of this was silver in the National. Then they changed the rules, imposing an additional handicap of minus 200 points on every competitor under the age of forty, effectively taking us out of the reckoning. I had one more year of modern triathlon and biathlon in 1994, unsurprisingly without medals, and then decided to return to running. I had joined the newly-formed Calne Running Club and thought it was time to say goodbye to the track, return to my cross-country roots and enjoy some low-key road races and relays.

The road relays were fun, always ending in the pub. I was elected club captain and also ‘player-manager’ of the Wiltshire men’s cross-country team. My final race of the 1995/96 season was in the Wessex League at Blandford where I clinched third place overall after improving from eighteenth in the first round to second. It was twelve years after my last medal in the same league. The standard in the league had slipped, like most of UK distance running. It was my final race as a senior because two weeks later I turned forty.

And became a veteran.

I wasn’t tempted by the disappearance of the 200 points penalty that a return to modern triathlon would bring. Armed with the knowledge gained from coaching and coach education as well as twenty-three years of running, I was preparing for a season at 800 metres and 1500 metres.

Not the marathon?

Here’s how the conversation goes, one that has been repeated ad nauseum many times since the marathon boom of the early eighties.

‘So, you’re a runner, then?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Marathons?’

(Notice it’s always ‘marathons’—plural—as if one marathon isn’t enough.)

‘No, not marathons. I run track and cross-country.’

‘How far is that, then?’

‘Well, there’s 1500 metres on the track.’

‘1500 metres: that’s not even a mile.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Not much of a challenge, is it?’

‘Well, it depends how hard you run it.’

‘But marathons are a bigger challenge, aren’t they? You could move up to marathons, couldn’t you?’

‘No, thanks.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because I enjoy running 1500 metres and cross-country. I want to try my best to improve my times and win championships.’

‘How far is cross-country, then?’

‘It varies, usually about five miles.’

‘Oh well, then you could probably manage marathons; really test yourself.’

*******

Approaching the bell at the end of the first lap of the 800 metres at the South West Veterans Championships, Exeter.

A balding runner moves up alongside me, vying for pole position.

An old balding bloke? I can’t let somebody like that beat me. But, hang on: I’m an old balding bloke. (I’ve been warned that there’s something uncomfortable about being at an event when everyone is over the age of forty.) I pick up the pace and hold the bend.

And win in 2:05.0.

An hour later, I’m watching the back of the early leader of the 1500 metres as he pulls away.

But only so far, then I start to reel him in.

200 metres to go, I’m on his shoulder. Do I take it on now or wait until we’re in the final straight? I’m feeling good: let’s go now.

I win in 4:15.8.

It’s my first veteran-only competition and I’m a (double) South West Champion.

So far, so good.

*******

On reaching the age of forty, many runners think it’s going to be easy: they’re the youngest, all they have to do is match times achieved in their late thirties and they’ll win. It’s not that easy: it’s more about managing your inevitable decline than being a slave to your times from younger days. And it’s competitive: standards are high at the top level of the ‘vets’.

My training was going well. I was following the five-tier system: progressive sessions at 400 metres, 800 metres, 1500 metres, 3,000 metres and 5,000 metres pace. A progressive competition programme was more of a challenge: there was the Wiltshire Senior Championship and the occasional open meeting but Calne had no track team: I was the only one. However, I did manage to run 2:01.2 for 800 metres leading up to the British Veterans Championships and a return to Exeter.

The 1500 metres on Saturday was a straight final. Showing some of my old aggression I led for the middle section and wound up fifth in my fastest time of the season—4:12.38—a pbv (personal best as a veteran). Looking at the results on the board, I thought about changing my name to Dave: all four in front of me were Daves. I won my heat in the 800 metres on Sunday and finished last in the final. This could have been another crying-in-the-showers incident. However, twenty years older, I reflected that 2:03.70 was a respectable time, it was my third race of a weekend that included a season’s best exactly when it should be—in the final of the most important event of the season—and it had been a successful return to the track.

Encouraged, I wrote to the Scottish Veterans team manager, asking to be considered for selection in the Veterans’ Home Countries International Championship, coming up in November. I wrote about my performances that season on track, the previous season on the country and my fourteenth place in the Scottish in my younger days. Fingers crossed, I posted the letter and waited for a reply.

Meanwhile, we were hosting the first Calne 10K road race, which was to incorporate a veterans’ race and a trophy.

Dad’s trophy.

The year after Dad died, Mum had commissioned a trophy in his memory for the first veteran to finish the annual road race in Airdrie. When the race ceased to be held, the trophy lay dormant in Mum’s attic, from where I reclaimed it and had a new inscription added: First veteran to finish the annual road race in Calne. It was a proud moment when I walked up wearing my Airdrieonians shirt to receive Dad’s trophy.

Unlike the long-running exchange of letters leading to my selection for British Colleges, there was a straightforward reply from the Scottish Veterans manager. It confirmed my selection for the Scotland over forties’ (M40) team and provided details of where and when to meet. With the minimum of fuss, I was on the edge of achieving a lifetime’s ambition: to run for Scotland.

It wasn’t the World Cross but it was the only international veterans’ event of the year when top quality in-depth was guaranteed. Although only five nations gathered for the British & Irish International Cross-Country Championships, this was usually a higher standard than the European and World Championships. Whilst there were stars amongst athletes from all over Europe or the World at the continental or global championships, nobody got there by selection: they all entered as individuals and paid their own way. On the other hand, only selected athletes made the start line at the British & Irish, and competition for selection was fierce.

The championships were hosted on a five year cycle by England, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales and, as in 1996, Scotland. In less than glamorous circumstances, I drove to Airdrie after school on the Friday, Susan drove Mum and me to Irvine for the race on Saturday, and I drove back down to Calne on Sunday.

It was a huge thrill to pull on my Scotland vest and line up to represent my country at last. In my excitement I started too quickly but recovered and ran a sensible race thereafter to finish twenty-fourth (eighteenth M40). Overtaking another Scotland M40 in the run-in, I had squeezed into Scotland’s scoring four, helping the team to silver medals. It was my first international medal, although I didn’t see it until a week later: we left before the presentation, because of my early start and long drive home the next day. Once again, I was an unknown: turned up, ran the race, didn’t have time to get to know the team, went home.

But nothing could diminish my sense of achievement. I left wanting more.

*******

Looking for more regular races as my second track season as a vet began, I joined the British Milers’ Club (BMC), which had been set up to raise standards in middle-distance running by providing regular, meaningful competition. I ran for the BMC Vets in a successful world record 4×1500 metres attempt at Watford. Unfortunately, I was in the ‘B’ team, which failed to finish. It was no compensation that we ran a decent 3×1500 metres. However, 4:10.6 was a promising start to the season, nearly two seconds quicker than my best.

But I would run no faster.

It was nothing to do with injury, bad planning or over-racing.

It was the start of a long period of illness.

Brought about by stress.

At school.

It was another crisis.

I came to the village school in January 1996 with a good reputation, forged during six years in Swindon, where amongst my post-Snap projects had been writing and implementing a new Physical Education policy and scheme of work, and grounds development. Raising funds from grants, I coordinated the planting of thousands of trees, hedging, shrubs and flowers. Together with new fencing, bird boxes, extensive pathways and a redevelopment of the pond area, the grounds were transformed from a featureless ‘green desert’ into a haven akin to a nature reserve. Every child in the school was involved: from planting a bulb to designing plans.

It was in the midst of this transformation that the headteacher of the village school came to observe me in my classroom. She was visiting all candidates who were due to interview for deputy head at her school. She liked my style of teaching and saw in me what she felt her school was missing: a leader with a firm understanding of the curriculum.

I should have heeded the warning signs but, excited by an opportunity, I was in denial.

It was my tenth interview for deputy headship: could I not see that the previous nine were trying to tell me something? There were ninety children on roll in the village school but the headteacher did not teach a class. Did that not ring any alarm bells for me? She wanted a deputy head with a firm understanding of the curriculum. Is that not the headteacher’s job? What had she been doing with the curriculum so far? The Swindon school was in a relatively poor area where most parents took little interest, whereas the village school was in a middle-class area, where most parents wanted to be involved, not always in a positive and helpful way. Could I not see that transplanting ideas and methods from one school to the other was going to cause problems?

If only we could benefit in advance from hindsight. In ignorance I blundered into the crisis. As well as teaching my class full-time, I developed policies and schemes of work—none of which were already in place—in every subject area. Inevitably, in the limited time available, this work was rushed, without full consultation or involvement of staff and governors. Everything had to be in place by the end of the year and a half between a worrying pre-inspection review (before my time) and a forthcoming Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED) inspection. I tried to teach my class with the same methods that had brought success before, not giving myself time to think that this school and these children required a different, bespoke approach. Almost idiotically, and shortly after joining the school, I volunteered to coordinate another grounds development project.

The number on the school roll increased to over a hundred during that year and a half.

And still there were only three classes, not the more obvious four.

My own class grew from thirty-three to thirty-nine, made up of all of the Years 2, 3 and 4 children.

And still the headteacher did not teach a class.

It was a recipe for disaster.

By the time the inspection week came along, I was running ragged.

The school did not fail the inspection.

Neither did I.

The school was not put into special measures.

Neither was I.

But strong recommendations were made.

And it appeared that I was to be the scapegoat.

Had I suddenly changed from being a good teacher to a poor one?

*******

‘It’s not our job to advise; would that it were’.

‘Improve the teaching in the middle class.’

‘This is down to you.’

‘If you walk out of that classroom now, you’ll never come back.’

‘Go and have your nervous breakdown somewhere else.’

*******

Driving home on Friday at the end of OFSTED week.

I haven’t failed, but I’m a failure.

As a teacher.

As a husband.

As a father.

As a person.

When I get home and walk through the door, what am I going to do?

What do I say?

How am I going to get through the weekend?

And go back to school on Monday?

How do I face that?

How do I face…

Anything?

On the edge of a steep drop.

Why not…

Drive the car…

Over the edge?

Turn the steering wheel.

Crash through the fence.

Let go of the wheel.

Let go of everything.

Let myself go…

Over the edge.

End it all.

Is the drop steep enough?

*******

The edge of a cold loch.

I didn’t do it then.

I found a way forward.

I won’t do it now.

I’ll find a way.

But how, what?

*******

Friday evening.

I’m sitting on our kitchen floor, rocking back and forth.

Jane makes an appointment with our doctor.

For Saturday morning.

*******

‘You’re ill. You’re not going back to work. I’m signing you off. Taking you out of the situation that’s causing you this stress.’

I’ve never been off with stress before.

I’ve always kept going.

Have to keep going.

Can’t let the children down.

Can’t let the family down.

Have to keep the income coming in.

‘You’re ill. Your priority is to get better. It’s the only priority.’

Okay, I’ll go off sick.

But after I write the reports, after I take the class on a planned trip, after I finish…

‘No. Someone else can do all that. You’re ill. Go off sick now.’

*******

I’m in my classroom.

On Saturday morning.

We’re all there: Jane, Sam, Emma and me.

It’s a compromise.

Put things in place to make it easier for a supply teacher to take over.

Then go home.

Phone the head.

Go off sick.

Stay off.

Three hours later, that’s exactly what I do.

*******

Three weeks later.

Sixteen years of teaching plus four in training.

Twenty years.

I had never been off sick for three consecutive weeks before.

It had never before occurred to me to go off sick, despite the obvious signs and symptoms that I was suffering from work-related stress. I had responsibilities to the school. I had to keep working, get through the OFSTED week, do my best to take the school forward.

Nor had it occurred to me to give up teaching altogether. I had responsibilities to the family. I had to provide for them. How would we manage without an income?

I had responsibilities to myself, too. I had trained for four years and had been teaching full-time for sixteen. It was my vocation. It was part of me. I couldn’t give it all up after twenty years.

Could I?

Then I discovered that income wasn’t an issue: I would be paid 100% of my salary for six months and then 50% for a further six, when sick pay would make up the difference. For a whole year we would be no worse off.

A whole year.

Would I really be off sick for a whole year?

Then what?

‘Deal with that when it comes,’ my doctor advised. ‘I’ll keep signing you off. Concentrate on getting well.’ He prescribed anti-depressants and referred me to a mental health consultant.

I thought I was the only one.

‘You’re not the only one,’ my doctor assured me. ‘There are hundreds, maybe thousands of teachers just like you.’

This was 1997.

People still didn’t understand mental health, especially men’s mental health.

But there were exceptions, including our GP. It could have been so different: he could have been dismissive. And I had experienced enough of that when I was first injured. But he understood, knew exactly what to say and what to do. Set me on the road to recovery.

A long road

Chapter Fifteen: Tribunal

Who were these thousands of teachers like me? I’d never met any of them. Never heard of anyone. Were we all in denial?

Until I bumped into a former colleague from Swindon, outside the Co-op in Calne. She was off sick too. Her feelings were similar to mine: despair, uselessness, anger, wanting to blame someone, blaming herself, feeling alone despite the support of family. So, I wasn’t the only one but did that help?

At this point I should be able to recount how running saved me: how it provided a release from stress, a distraction, a different focus, time to think and make decisions about the future, a new way forward, a happy ending.

That’s not what happened.

My GP had recommended exercise. That wouldn’t be a problem, I had assured him.

But it was.

At first I hung up my spikes and went out for a run over the hills, trying to relax. I went swimming, cycling and walking the dogs, all at times when I would have been in school. It was a relief. It was almost revenge: doing something that I wanted to do instead of being a slave to OFSTED. If only the inspectors knew how they destroyed lives.

After a few weeks I started to train for the track again. Released from the physical exhaustion of teaching, I had much more time to recover from training, which was going well. I resumed my racing programme.

Which didn’t go well.

My 5K road relay times were a minute slower than pre-OFSTED. Meanwhile on the track, I would get into good positions but when the time came to dig deep and find another gear, there was nothing there. There was no competitive urge. It felt like adrenaline had run dry. Aggression had disappeared.

I hung up my spikes again and went for a run.

This should be when I describe how I connected with nature, reconnected with myself, rediscovered…

Something.

I didn’t.

I described my feelings to the mental health consultant. Were the drugs suppressing my competitive instinct? Did they have an effect on adrenaline? The consultant confirmed that there was some truth in what I was suggesting. Drugs were supposed to be help me feel better and recover from illness. If they were having an adverse effect on running, it was like putting up barriers, a roadblock on my alternative route to recovery. It was counter-productive.

We agreed that I would wean myself off the drugs.

By the end of the summer I was drug-free, and preparing for my second cross-country season as a vet. Having regained some confidence, I had started to volunteer at our local sports centre. Where, after a career of working with young children, I discovered that I had an affinity with older people. Months after withdrawing into myself, I gradually crept out of my shell and chatted with the older people. They were happy that a younger person was taking an interest in what they had to say, and they were interested in me, too. Although I never revealed the full story of what brought me to their group as a volunteer, they seemed to know. Life experience brings perception.

I took them on weekly walks, which usually ended at a café or a pub for lunch, and I started to assist the fitness instructor in the gym. The manager wanted to keep me on and, as he couldn’t pay me, the centre funded my attendance at courses: fitness instruction, the National Pool Lifeguard Qualification (NPLQ), exercise referral, older people’s exercise, even an IT course. Over the course of a year, I was setting myself up for a career in leisure and fitness.

I sent a new doctor’s note to the headteacher every month without fail. So far, there was no pressure to return to school. I was beginning to relax into volunteering and running. One step at a time, I was starting to feel good about myself again: doing something useful, being liked.

And running well: I was called up for Scotland again.

It was odd that the British and Irish always took place in November, much nearer the beginning of the season than the traditional place for major championships at the end. The selectors either had to arrange an early trial race or rely on current or previous form. In my case, it had to be previous form: I had done nothing since the beginning of the track season. Scotland put its faith in me, which made me feel even better about myself.

I wasn’t going to let Scotland down.

It was Northern Ireland’s turn to stage the races. Curiously, Scotland arranged a coach journey, not flights. My journey was longer than most but I saw it as a continuation of my recovery. It was my first time away from home since going off sick. I would miss the family but I was looking forward to an adventure.

Train to Glasgow, then Airdrie to stay a night with Mum. Then train back to Glasgow, Mum coming with me to see me off. Team coach to Stranraer, ferry to Belfast, coach to Ballymena.

On the back of good early season form I ran confidently, finishing seventeenth (fourteenth M40) and third Scot. It was an improvement on the previous year. More significantly, I belonged. The long journey by coach and ferry, the two-night stay in the team hotel and the presentation and dance all fostered team spirit. Unlike the mad dash of my international debut, there was time to get to know my teammates: Archie Jenkins, our top runner, always up for it; Davie Fairweather, team manager, always there for you; Iain Stewart (not that Ian Stewart), always close to my standard; Colin Youngson, another teacher, always eloquent; Jane Waterhouse, an adopted Scot, always there or thereabouts; Hazel Bradley, always cheerful.

I took my good form and renewed confidence with me on the long journey home and into the remainder of the season. Sixteen years after my first attempt, I finally won the senior title in the Wessex League, with two first places and two thirds. I then returned to Scotland for the Scottish Veterans Championship and drove back home two days later with a bronze medal in my pocket. I remember having last year’s winner in my sights in the run-in. It was Fraser Clyne who, as a student, had beaten me in that representative match in Camberley and went on to become one of Britain’s top marathon runners. I was in exalted company again, knowing that one final thrust would take me past Fraser and into the medal positions. It was a proud moment when I walked onto the stage to receive my first national cross-country medal.

As a successful season drew to a close, I completed my leisure and fitness training. I had been shy at the beginning of the fitness instructor course, amongst a group made up mostly of ex-forces personnel and PE student-types. Slowly but surely I found my way. Passing the practical assessment, which required a demonstration of perfect technique in free weights, was a landmark achievement for me, such a contrast from the destructive nature of OFSTED. In regaining my self-respect, I also earned the respect of the rest of the class, particularly at the final assessment when I led them in a circuit training session.

The course enhanced my own exercise routine, adding quality weights training to my usual long runs, cross-country and hill repetitions supplemented by a weekly swim and regular cycling. My mileage had crept up from the thirty miles per week of my modern triathlon days to around forty-five: not excessive. I had been able to maintain quality and quantity for a whole season and I wasn’t injured. It proved beyond doubt that a sustained period of regular, sensible training leads to good racing.

Running was helping me recover from the trauma of OFSTED, after all. Volunteering and vocational training were providing me with a new purpose in life. However, school was never out of my mind. The end of a year off sick was approaching. By now, I had decided never to return to the classroom. What was I going to do when the salary stopped coming into my bank account? Working in leisure wouldn’t pay the bills. Even if it did, I couldn’t get a job until my contract at school had ended. Rather than let it happen to me, I decided to influence the way that it ended.

History was repeating itself. My recoveries from injury had taught me resilience, proactivity and determination. I sought advice and guidance from my GP, my mental health consultant and my union rep, Craig.

Together we formed a plan.

The doctors agreed that, when my teaching contract ended, I should be eligible for retirement on the grounds of ill health. And yet, they knew that I was getting better. It was a dilemma. At the one extreme, I was volunteering, training for a new career and running internationally; at the other, I needed to show that I was unfit to return to the classroom. Which was undeniably true: no matter how well I seemed on the outside, each and every thought of facing my demons again filled me with dread, caused palpitations, loosened the bowels, made me feel physically sick.

In order for me to extricate myself from teaching, fully recover from the crisis and start again, both extremes had to be in place at the same time. This was the challenge faced by my union rep and me as we attended a tribunal at school.

*******

It’s the first time I’ve been at the school gates since that Saturday morning almost a year ago, when I was here with the family, preparing to leave it all behind.

Conspiratorially, Craig and I turn to each other. He sighs, gives his shoulders the slightest of shrugs, his facial expression saying: here we go, good luck. Taller than me, he pats me gently on the back, almost fatherly, and we walk through the gates and into school.

Two and a half years ago I walked anxiously through these same gates, relishing the opportunity that my first deputy headship would bring, anticipating a turn of fortunes, an advancement of my career.

How could I have known that those fortunes would turn against me? That, far from an opportunity, it would be a nightmare? Far from advancement, it would end my career?

And now, anxious again, anticipating a different turn of fortunes, I hope to walk away again at the end of the evening with another opportunity: to receive an ill health retirement pension. Then I can afford to start afresh. Just like the interview nearly three years ago, everything depends on how I present myself in the next hour.

We’re in the library, the same room as the interview. Once again facing a panel of judges. Do any of them understand how I feel? Do they realise that they hold my future in their hands?

I’m here tonight to shape my own destiny. It’s a job interview and OFSTED inspection rolled into one. It’s ‘down to me’ again.

The preamble describes events since OFSTED: no interim deputy head, only one of the original trio of teachers left (ironically, a previously failing teacher whom I mentored so well that she performed better than all of us during OFSTED), a switch from three to four classes, the number on roll continuing to rise (but still the headteacher doesn’t teach), poor standard attainment tests (SATS) results, a lowly place in the school league tables, parents up in arms. Some of the governors are looking at me as though it’s my fault, the OFSTED scapegoat their obvious target.

But hang on, the Year 2 stats, which I coordinated, brought better results than previous years, and the school roll began to rise at a rapid rate when I joined the school, so I can’t have been all bad. I decide not to comment. Let them ramble on.

‘I wasn’t consulted on this,’ states the headteacher of the (hypothetical) phased return that Craig and I sent in advance of the meeting. Her letter, inviting me to a pre-meeting, arrived on the same morning as the meeting. And sent me into a state of shock. Luckily I managed to contact Craig, who phoned on my behalf to cancel the meeting.

‘I fail to understand how, after all this time, you could be shocked by an invitation to a meeting with your headteacher,’ one of the governors, a vicar, tells me in accusation.

You don’t understand mental health, I think. For a man of God, you don’t understand much about human beings, do you?

But I say: ‘May I remind you that I’m off sick?’ This isn’t the time to be confrontational.

There are two vicars, representing two churches. The other tries a different approach, not unkindly: ‘Do you really think that this phased return will be the best thing for you and the school? Do you honestly want to come back?’

He knows. I like him. When I was teaching, I liked him. During the week after OFSTED, I trusted him, arranged to meet him, went to the vicarage, described how I felt, that it wasn’t all down to me, that they should also look to the headteacher. I confided in him. I admire the compassion of this other man of God.

I lie.

‘Yes.’

*******

Craig and I return to the library when summoned. We’ve been waiting in the staff room while the panel deliberates. It’s so like a job interview that it’s uncanny. Only this interview is to lose a job.

They have made their decision. They tell me, with regret, that they have decided to dismiss me on the grounds of ill health.

I hold my head high as I walk around the room, shake hands and look each and every one of them in the eye.

Eyes down, the headteacher avoids my gaze.

So does the first vicar.

The second vicar returns my look. Is it sadness? Is it disappointment? He may well be the only governor who truly understands what happened here tonight. We understand each other.

*******

‘You coped well. Remarkably well,’ says Craig afterwards. We’re now in the pub, and I’m sinking a pint in relief. It’s possibly the best pint I’ve ever tasted.

I treated the tribunal like a competition. I had my race-mask on the whole time. It was an act. I had trained for it and Craig was my coach. We had prepared well, and it appears that we have achieved the desired result.

Surely I can’t be denied an ill health retirement pension after the school has dismissed me on the grounds of ill health.

*******

I could and I was.

My application for ill health retirement was rejected. The panel (yes, another panel) suggested that as I had been volunteering, I was well enough to work and therefore not unwell enough to receive an ill health pension.

My GP and consultant intervened on my behalf, and there was another anxious wait.

Meanwhile, my year of volunteering over, I took on some paid work at the leisure centre. Not surprisingly, the relationship altered and there was less work for me. It was the odd shift in the gym and lifeguarding now and again. It wasn’t enough. I needed to find another job. But even if I found a full-time job in leisure and fitness, it wouldn’t pay as well as deputy headship. It wouldn’t even pay the bills. We needed that retirement pension. The wait continued.

And then, like a knight in shining armour, the old mantra rode to the rescue: when your running is going well, everything is going well. Two letters arrived on the same day: I was selected for Scotland for the third year in succession, and I was going to receive a lump sum and annual teachers’ pension.

Shortly after another improved performance at the British & Irish, and a sizeable deposit in my bank account, I was offered a new job in a leisure centre in Swindon. It was temporary and part-time, but my hours would increase with overtime and coaching, and there were many opportunities across the borough for permanent work.

At last, after the nightmares of the last three years, the crisis was over.

It was a new beginning.

Chapter Sixteen: Targets

An ex-deputy headteacher sitting in a lifeguarding chair, I was leaving myself open to ridicule. I was the oldest member of the team, an oddity. However, I was accepted for being different. I soon settled into my new role and routine, and seemed to be well-liked by customers and colleagues. It was the beginning of six mostly happy and contented years.

And safe: I didn’t have to go back to school. I would never have to face that stress again.

As promised, the hours of work increased to full-time in the gym, plus coaching and overtime. I taught older people’s exercise classes every week, re-establishing a rapport with older people. I learned how to climb and qualified as a climbing instructor. I also helped to start an exercise and social group, to support adults with mental health problems. Some of my colleagues looked upon the group with suspicion. When they saw ‘mental health’ on the duty sheets, they stood back, frowning and said, ‘mental?’

‘They’re not mental,’ I explained. ‘They’re people dealing with challenges, just like you and me.’

It was the turn of the century and people still didn’t understand mental health. But here in Swindon they tried: they changed the name on the sheets to ‘Health’. The name stuck and the group is still running to this day.

My own mental health was improving. The pension, coaching and overtime supplementing my fitness instructor salary, we were no worse off financially than when I was deputy head. That brought security to the family and to myself.

I was respected for being good at my work and more importantly for being myself.

But I was having nightmares.

*******

There are no children. It’s the middle of term and I’m in the staff room, preparing lessons. I’ve returned to teaching on a trial basis and I’m doing okay. It’s a turning point. Do I keep going, rediscover my vocation but run the risk of another breakdown? Or do I give it up at the end of the trial period and return to the comforts of my job at the centre? I don’t know, because I wake up, the bedsheets drenched in sweat. The nightmare, with minor variations, returns another night, and still I don’t reach a decision. I never do.

The nightmare comes back again and again at times of stress.

And still does.

Twenty-five years later.

*******

The hours were long at the leisure centre, but the environment and routine were conducive to training. I had free use of the gym, pool and climbing wall before and after shifts. On days when an evening shift was coming up, I enjoyed running in daylight, free at last from turmoil and stress. Over the hills and Far From the Madding Crowd, I was finally connecting with nature.

I never wore headphones: I wanted to enjoy the full experience. I didn’t want to block out one of my senses. As well as admiring patchwork fields from a hilltop, I wanted to listen to the skylark singing high above. I didn’t only smell the earth: I heard the squelch of mud underneath every stride. I felt the wind on my face and heard it chasing leaves along the trail. I tasted rain on my tongue and heard it splashing in the puddles.

One day I ran above the clouds. The sun was shining high but the valleys were shrouded in mist. Coming across some people enjoying a spot of flying with model aeroplanes, I thought: me too; I’m flying. That’s what it felt like. A natural high.

Once a week I trained on the track with Swindon Harriers, including Pete Molloy, World Veterans Champion at 1500 metres, a member of that 4×1500 metres world record team, an inspiration if ever there was one, and an ideal training partner. Although a few years older than me, Pete was faster but not so much faster that I couldn’t stay fairly close to him. A friendly Yorkshireman, he always had an encouraging word for me.

Minor injuries and illness aside, my performances in competitions were consistent. I won the Wessex League veterans cross-country title every year and was a regular in the Scottish Veterans team. On the track, I was often in the minor medals at the Scottish Vets and once at the British. I wasn’t slowing down much, and age-graded tables demonstrated that in age-related terms I was improving.

I ran a faster actual time for 5,000 metres (15:40) in my mid-forties than I did at any time in my thirties. That was the season of my first taste of international track competition, when the World Veterans Championships came to the north east of England. Without overseas travel and accommodation, I could afford the entry fee. The 5,000 metres was run on a heat-declared winner basis: three heats, based on submitted entry times. My best performance at the time of entry was slower than sixteen minutes, placing me in the ‘B’ race, which I won. It was a huge thrill to win a race at the World Championships but I was outside the top twenty overall. Not exactly setting the world alight.

A strange aspect of veteran athletics is that you look forward to growing older and moving into the next age group, when you’ll be the youngest and therefore in theory have more chance of winning. Entering my final year as an M40 I decided that, rather than wait until I was a year older, I would set myself a new challenge: join Swindon Harriers for regular competition on the track. Returning after a long absence to Southern Men’s League Division One, I was a consistent points scorer for the team in my first season and improved steadily, from 16:16 for 5,000 metres in the opening round to 15:51, alongside 4:14 and 9:07 for 1500 metres and 3,000 metres. Meanwhile, the team had performed so well in the league that we were invited to the British League qualifying match at Bedford. Selected for the 5,000 metres, I had a problem: I was recovering from minor injury and a wasp sting, and working a morning shift at the gym. To cut a long story short, I drove to Bedford after work, arrived just in time for my race, finished second ‘B’, we qualified for the British League, and I won the Club Athlete of the Year award.

At the age of forty-five, I was going to make my debut in national league athletics.

But before then, there was a season of cross-country, and it was Ireland’s turn to host the British & Irish. True to form as a late starter, it would be the first time I had ever been on an aeroplane. The thought of flying didn’t worry me at all: it was fear of being in the wrong place at the wrong time that made me feel anxious. It helped that Clara was going to collect me at Dublin and take me to Scotland’s team base near Navan, County Meath. Clara was making a life for herself in Ireland. Long after her early promise as an athlete, she was now a Leinster hockey player.

My spikes caused a minor commotion as I made my way through airport control, but apart from that it was a smooth operation. The bustle of the departure lounge was exciting. Where were they all going? Were they on holiday, business or a stag/hen weekend? It wasn’t difficult to spot other runners going to an international running championship: we all had that lean and hungry look about us. I loved the anticipation as we shuffled from the departure lounge into the queue to board the plane. Excitement building like the buzz of the engine under the seats. That unique feeling in your stomach as the plane left the ground, and then you peered through the tiny window at the map-like view of city, then patchwork fields, then shimmering estuary. Into and above the clouds, waiting to relive the experience in reverse as your destination neared.

While the other teams were enjoying the comforts of hotels in Navan, the Scotland squad was accommodated at the race venue, in a building something like a cross between a youth hostel and a monastery. It had character but it was dark and cold. We were asked to turn the lights off whenever we left a room or corridor, which later caused more than one of us to bump into walls as we fumbled in the dark to find the switch. The heating went off automatically but too early: we felt cold. When one of the team went to reception to ask if we could have the heating on, the reply was: ‘Well, yeez only paid for bed and breakfast.’

The course was on the side of a hill leading down to the river, not far from the site of the Battle of the Boyne, where in 1690 King James II of England and Ireland and the VII of Scotland lost to King William III, sealing James’s failed attempt to regain the throne. There were no such problems for the England cross-country teams: as usual, the most populous nation won most of the individual and team honours. I won my own honours and personal battle to improve, year on year, in this race. I loved that hill as I picked off runners one by one, feeling like I could pass people all day. I entered the finishing straight in eleventh place, only losing out in a sprint finish to Ireland’s Colm Rothery, which was no disgrace as Colm would, the following summer, achieve his targets as World M40 Champion at 800 metres and 1500 metres with 1:52 and 3:55.

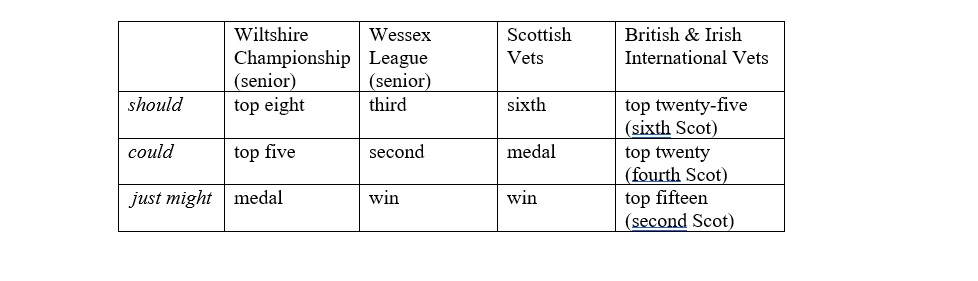

My own targets were more modest but unique to me and achievable. Working in a leisure centre brought me into contact with coaches from different sports, and it was a swimming coach who introduced me to tiered targets. Setting single targets such as ‘win the national’ or ‘beat four minutes for 1500 metres’ will result in disappointment if you fail to achieve them. On the other hand, setting targets that are achieved too easily can reduce your motivation. The tiered method sets targets at three different levels: should, could and just might. There are targets that you should achieve if you stick to your training and racing plan and don’t do anything silly. Then there are those that could be achieved if you stay relatively clear of injury and illness, and build up to and approach the major competitions with confidence. On a perfect day, when everything in place and all is right with the world, there are dream targets that you just might reach.

At the beginning of the season I had set myself the following targets:

So I achieved my ‘just might’ target at the British & Irish. Twelfth overall was twice as good as my debut when I was four years younger. I was eleventh M40, which meant that only one M45 (Nigel Gates) beat me. Four months before my forty-fifth birthday, I had a lot to look forward to as an M45, but there were a few more races to run before then. I went on to finish second senior in the Wessex League (could), third senior in the Wiltshire Championship (just might) and third M40 in the Scottish Veterans Championship (could).

Alongside these triple-tiered targets, and five-pace training (in the track season), I had been following a triple-periodised year’s plan since first gaining selection for the annual international match. Much like the double-periodised year with twin peaks at the National Triathlon and Biathlon Championships, the ‘triple’ was designed to help me reach a peak three times per year: the British & Irish in November, the climax of the cross-country season in March and a series of track races in the summer. Unimaginatively I called the phases: Cross-Country 1, Cross-Country 2 and Track. In theory, the system made sense. In each of three short seasons, I would lay a training base, introduce progressive sessions of good quality, and then taper as the key races approached. In practice it was fraught with difficulties. For instance, most races didn’t slot themselves conveniently into the schedule, and the peak races were not exactly four months apart. There were few opportunities for cross-country races in the build-up towards the most important race of the year: the British & Irish. Most significantly of all, if you succumbed to injury or illness during a six-month season, generally you had time to get over it, but if the same thing happened in a four-month season, the key competitions could be upon you before you’ve had a chance to recover.

It may sound complicated. Distance running isn’t complicated, is it? You just run distance, don’t you? But I was learning from experience, including painful mistakes. I was doing my utmost to get the best out of myself.

Cross training provided variation. There was a weekly swim, consisting mainly of general endurance in the early stages of each phase, followed by more specific endurance in the later stages. Twice weekly gym training was in two parts: endurance, on the rower or treadmill, and strength.

As a fitness instructor I had mixed feelings when I saw customers walking or running on a treadmill. It’s better than doing nothing but it’s not as good as the real thing: why pay for an hour on a treadmill, going nowhere, when you could do the same outdoors for free? However, many customers don’t have the confidence to exercise outside, and appreciate the security of the gym and, I like to think, the support they receive from the instructors. At least they should put the treadmill on a 1% incline or higher, when there is less assistance from the rolling belt and less chance of their legs feeling like lead weights if and when they do venture outdoors.

For me, as an athlete, the treadmill opened up a new realm of training opportunities. I designed my own programmes, such as a continuous run with set changes of incline: a tough, hilly challenge during the early stages of each training phase, and a programme with set changes of speed for the later phase. The treadmill belt is relentless, similar in a way to a faster opponent in a race as you try to keep up with him. I endured some really tough sessions, exceeding my theoretical maximum heart rate and pushing myself to my psychological limit to maintain the set pace, willing the treadmill to hurry up and get onto the easy bits. They were emotional times. Customers saw a different side to their quiet instructor: divulged of bulky tracksuit, stripped down and skinny, giving the appearance of floating (so they told me) through the easier sections but gasping for dear life at crucial points in the programme. Those ‘points’ seemed to me more like hours of pain, and there was huge relief and a sense of achievement at the end of each session, which I’m sure prepared me well for races.

My strength training, all with free weights, was also progressive: fifteen reps of all exercises in the first month; three sets of ten, for example legs/biceps/triceps/abdominals for session one and back/chest/shoulders/abdominals for session two, during the second month; sets of ten/eight/six reps at increasingly heavier weights in the third month; and finally, two or three sets of six reps for the fourth month. There were also strip-sets, where you reduced the weight as you increased the number of reps, eventually working a muscle group to exhaustion, and many other variations.

Climbing introduced new elements of technique, teamwork and daring: I loved how different it was from everything else in an already wide ranging training programme. Cycling was taking a back seat, because I simply couldn’t fit everything in.

Despite this wide variety, I still managed to increase my running mileage into the fifties and, a couple of times, sixty. However, as a mature campaigner in my mid-forties, I listened to my body, curbed my enthusiasm, restricted mileage to a sensible level and managed to recover from minor ailments to complete a final, successful year as an M40.

And move up an age group to the promised land of the M45s.

Chapter Seventeen: Promising

I remember a conversation with the eloquent and motivational Colin Youngson, when I revealed that I was proud but frustrated at often finishing second or third but never first in National Veterans Championships. He reassured me that I had established myself as a regular and reliable competitor of a good standard. There would come a time when everything clicked and I’d ‘clean up’.

Would that time be 2001/2002, my debut season as an M45, also my first in the British League? Our team manager at Swindon was Howard Moscrop, another inspirational figure and, like Pete Molloy, a World Veterans Champion (at 400 metres Hurdles). Howard was a down-to-earth man manager, who had a knack of encouraging athletes to turn up: no mean feat, with so many other distractions in the modern world. As a coach, he knew how to get the best out of individuals, leading by example and always showing his appreciation of each and every athlete’s contribution to the team. I was determined to make my contribution count and leave nothing on the track.

In a promising start to the season, I finished seventh in the 5,000 metres with 15:45, faster than I had run during my last couple of years as an M40. The higher level of competition inspired a self-confidence which I took to the Scottish Veterans Championships at Pitreavie, scene of my Scottish Schoolboys win twenty-seven years earlier.

‘GOLD AT LAST!’ I wrote in my training diary. Typically, I didn’t cross the line first as I was beaten by the M40 winner in both the 5,000 metres and 1500 metres but I was finally a Scottish Veterans Champion, twice on the same afternoon.

I followed up with 33:13 10,000 metres for fifth place overall in the British League Gold Cup at Eton, increasing my confidence even more, as a return to the same track for the British Veterans Championships beckoned in a fortnight’s time. I was due to run the 5,000 metres on Saturday and 10,000 metres on Sunday, not a sensible combination, but I wanted to keep my options open in a genuine attempt to win my first British Championship since the modern triathlon of 1993. Frustratingly, I was only fourth M45 in the 5,000 metres, running just outside sixteen minutes on a day when the winning time was slower than my best of the season.

It must be something about that track: my calves had tightened up immediately after the Gold Cup, not surprisingly after twenty-five laps, and now it happened again after the twelve and a half laps of the 5,000 metres. And I had to come back the next day to run another twenty-five.

*******

It’s so hot that there’s a water station on the back straight. There’s not a cloud in the sky as the sun beats down on us relentlessly while we circle the track.

Lap after lap after lap.

I’m in a group of four M45s. We seem to have made a collective decision to ignore the M40s: this is not a day for fast times, let’s focus on winning medals. One of the four will drop off the pace and miss out, and one of us will leave the group behind and win this race within a race. But not yet. The heat is oppressive, burning from above and radiating upwards from the track with every strike of the foot. Face reddening and eyes stinging, only slightly relieved by splashes of water along the back straight.

Lap after lap after lap.

I should be suffering more than most: my tight calves were painful last night in my sleep. But the pain eased during my warm-up, not that anyone needs much warming up today. It was more of a loosening up, and the heat, like a massage, counteracts the tightness in my lower legs. The tightness disappears, replaced by growing confidence.

Lap after lap after lap.

10,000 metres can be the most tortuous race on the track. If you judge the pace poorly and start too quickly, you spend the rest of the race regretting it, each lap progressively slower than the one before.

Lap after lap after lap.

This is where my treadmill training should prove its worth, maintain this monotonous pace.

But it doesn’t need to.

Because, despite the heat, it feels easy.

Because it’s not fast.

Because I’ve run faster.

Because I’m focused.

On the back straight with about half of the race to go, a long way to run. Jostling at the water station. A group of M40s lapping our group. I’m feeling strong, and latch onto the M40s, allowing them to tow me away from the group.

Two laps later. The M40s have dropped me for a second time. I glance behind. I’ve dropped the other M45s. All I have to do is keep going.

Lap

After lap

After lap.

Until the last lap.

Until the finish line,

Where I become a British Champion.

*******

It wasn’t a great triumph: it was a slow time, I was well down the field, lapped and outclassed by the top M40s. But I beat everyone in my age group, so I was a British Champion.

Two Scottish titles; one British; good times at 5,000 metres and 10,000 metres; points in the British League: it wasn’t a bad first season as an M45. Then came a patchy season on the country, interrupted by colds and chest pains. I was diagnosed with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)—intermittent, rapid heartbeat—but the results from an electrocardiograph (ECG) test were clear. Probably I was simply trying to fit all my training around working too many hours.

Nevertheless, I was in the midst of a decent period of training when the British & Irish came full circle to Scotland for my sixth consecutive appearance and first as an M45. The venue was Callendar Park in Falkirk, where I had represented Airdrie & Coatbridge Boys’ Brigade over twenty-eight years previously. I had a solid but unspectacular race, finishing twenty-fourth overall, some way short of my highest of twelfth a year before. However, as fifth M45, I beat my previous age group best of eleventh and, more significantly, helped Scotland win the team race. We were International Champions. It was brilliant for team morale, an achievement for each and every one of us. But it wasn’t an individual gold. I had yet to win gold in the Scottish Vets cross-country, let alone a medal of any colour in the British & Irish.

I missed the chance to win the Scottish because of illness. However, I finished fifth in the British Vets at the end of the season and won the senior title in my only season in the Avalon League.

My 2002 track season opened with a reasonable run in the British League: under sixteen minutes for 5,000 metres again, but something was wrong. There was a tugging in my groin, not enough to stop me running altogether, but restrictive, annoying, and which didn’t go away after rest. I eased down in training and called a halt to abdominal exercises because of the pain and reduced functionality, which was also making it difficult for me to demonstrate in the gym and at classes.

By the standards of previous delays this injury was dealt with swiftly. The gym’s resident physiotherapist diagnosed an inguinal hernia on 11 June, which was confirmed three days later by my GP, who referred me to a consultant in Swindon. On 17 July, the consultant told me that an operation was required and asked me what I did for a living. When I told him that I was a gym instructor, he asked, ‘Lifting heavy weights?’ A simple nod from me, and the process suddenly accelerated: on the last day of July I was in and out of surgery within two and a half hours.

An inguinal hernia is caused by a weakness in the abdominal wall, perhaps exacerbated in my case by an introduction to weights training relatively late in life (typical), coinciding with long road runs on a camber. Marathon runners talk about ‘the wall’ at around twenty miles, when their energy stores rapidly deplete. I never ran further than twenty miles, but my wall was breached, and the abdominal contents leaked into the inguinal canal, resulting in pain and a visible bulge in the groin. The surgery pushed the bulge back through the wall and held it in place with a mesh.

Simple.

But with a long and painful recovery.

Worse than any of my leg operations.

Worse even than the vasectomy.

On the first day after surgery, on eleven pain killers, I walked 100 metres.

With a stick.

On the second day I walked two hundred.

On the third day, down to eight pain killers, I had my first bath.

On the fourth day I took an hour and a half to have my first dump since the operation.

Awkward.

But what a relief.

Gradually, I increased my walking and introduced stretching, then gentle resistance exercises, then cycling and swimming.

My first jog (eight minutes) was on 20 August, the day after a scan gave me the ‘all clear’.

The next day I jogged a ten minute mile.

Look out World (Cross)! Here I come!

But progress was slow. Every stride downhill sent a searing pain into my testicles.

Ouch!

I was due back at work after five weeks but I fell down the stairs, damaged my ribs and had to add another week to my recovery. Eventually I was back at work on 12 September, returning quickly to practical duties and reached full training by the end of October.

It was no surprise that I declined an invitation to represent Scotland for what would have been a seventh consecutive year but I did make it to the Scottish Veterans Championships in March to come away with M45 silver, better than my three bronzes as an M40. I also won the Wessex League veterans title for the seventh year in succession and surprisingly finished 175th in the English National senior cross-country at the famous Parliament Hill course in London. That was higher than before I was a vet. Standards had been sliding down those muddy hills for twenty-five years or so.

The 2003 track season didn’t happen. I spent most of the summer nursing sore Achilles and hardly running at all. I was able to cross-train, which maintained my general fitness and helped me start to run again in September. However, ongoing niggles and recurring, minor illnesses held me back so much that I missed the British & Irish again and didn’t achieve a full training week until the end of the year. It was a pattern that would be repeated many times until the end of my career.

Not done yet, I had a whole month of full training behind me when I made a rare appearance ‘on the boards’ at the Kelvin Hall, Glasgow, for the Scottish Masters Indoor Championships at the end of January 2004.

Oh yes, we were no longer veterans: we were masters now. I guess ‘veteran’ had ex-military connotations but we had been veterans for years, and suddenly we were masters. I had an advantage over most others: I had been a master before in my modern triathlon days. But now, masters of what? We used to be addressed formally as ‘master’ when we were growing up, but now? We were not grand masters of chess. Nor did we play in masters’ golf tournaments. Had we attained mastery of our craft? Were we masters of our own destiny?

These thoughts never entered my head as I won the M45 3,000 metres and became Scottish Champion again. The following week I won the Wessex League February race outright. A fortnight later Jane, Sam, Emma and I were driving along the M4 on the way to Cardiff for the UK Masters Indoor Championships, where I would be amongst the contenders for a medal.

It did not go according to plan.

*******

For the spectators, sitting almost on top of the action, indoor athletics is ideal entertainment. Whereas in an outdoor stadium with a 400 metres track, you could be blissfully unaware of the shot put or high jump at the other end of the arena, everything around the vicinity of the 200 metres indoor track is so close that you don’t miss a trick. The noise bounces off the ceiling, walls and the track itself as the athletes’ feet thunder like drum beats, rhythmically, a crescendo rising each time they pass in front of your eyes. Lap after lap after lap.

For the athletes, waiting for their events, indoor athletics is nerve-wracking. You watch the action unfold and wonder when your event will actually start. Sure, there’s a timetable, but on this day, in Cardiff, it’s way behind schedule. So, what do you do? Warm up at the allocated time and then try to stay warm? Or estimate the delayed start time and warm up for that? To add to your anxiety, there’s no space indoors, so you have to warm up outdoors, where you can’t keep an eye on progress, or lack of it, on the track; are they catching up with the schedule or falling further behind?

Normally, I would choose the former: warm up on schedule and stay loose. But today, we’re about an hour behind, far too long to stay loose and warm. So I opt for the latter.

Big mistake.

I stay in my seat with the family and watch with them, explaining points of interest to encourage them follow and enjoy the action. They retain their interest and are looking forward to cheering me on.

If I ever set foot on the track: it looks like we’re still an hour behind.

After a visit to the gents I’m edging my way back to our seats.

But…

What’s going on?

The M40s and M45s are lining up

For the 3,000 metres.

My race.

The timetable is back on schedule.

How did I miss that?

‘That’s my race!’

Emma and Sam’s faces mirror my distress.

‘Get down to that start now!’ advises Jane.

But I can’t.

I’m still in my track suit.

I haven’t warmed up.

They’re all stripped off and under starter’s orders.

I’ve missed my race.

It’s the first time it’s ever happened.

We decide there and then to go home and not watch the race.

We’re in the car park before the bell sounds.

*******

To this day, Emma and Sam tell me how sorry they felt for me. They say that they can’t forget the shock and disappointment on my face.

Whether by coincidence or not, I developed an uncontrollable itch, just like after Dad died twenty years before. The nurse asked me if we’d changed our washing powder or altered our diet recently. She was looking for an allergy, but I couldn’t think of anything. Blood test results all came back negative. Then my GP, the same doctor who recognised stress at the end of my teaching career, asked me if I was taking any medication.

‘Only Ibuprofen for sports injuries.’

‘That’s it! Now you’re going to tell me that you’ve been taking Ibuprofen for years, aren’t you?’

‘That’s exactly what I was going to say.’

‘It doesn’t matter how long you’ve been taking something: allergies can start at any time of life.’

So that was it: no more Ibuprofen. From that day, whenever completing a medical questionnaire, I would always have to declare my allergy. A small price to pay to get rid of the infernal itching.

In time for the Scottish Masters’ Cross-Country Championship.

Which,

At last,

I won.

It wasn’t an outright win, of course: I was eighth overall but I was first M45.

Finally, I was a Scottish Cross-Country Champion.

Which of course made me proud.

But the next day, I was brought back down to earth.

*******

I’m outside Mum’s house, cleaning my spikes when a paperboy saunters up.

‘Aye,’ he says.

‘Aye.’

‘Whit ur they? Ur they fitba’ boots?’

‘They’re running spikes.’

‘Ur ye a fast runner?’

‘Quite fast.’

‘Ah bet ye couldnae beat me.’

‘I don’t know. I might: I’m a Scottish Champion.’

‘Aye, right.’

‘Aye: over 45s.’

‘Whit? Beatin’ a load ae auld grainfaithers!’

*******

And that was the 2003/2004 cross-country season.

Or half a season.

Two golds in the Scottish wasn’t a bad return.

For an old grandfather,

Which I wasn’t,

But I got the point.

The paper boy thought there was no cross-country for old men.

I was just an old man beating other old men.

And what’s wrong with that?

It’s better than being overweight and unfit like most people of my age.

We’re not the dying generation: we’re athletes.

We run: it’s what we do.

And as long as there are other old men to beat,

We’ll keep doing it.

Lap,

After lap,

After

Lap.

Chapter Eighteen: Building

The beginning of the 2004 track season gave little indication of what was to come later in the year. Flying the flag for the staff in a Superstars competition at the leisure centre, I didn’t place highly, but demonstrated an all-round fitness that enhanced my standing with our customers. However, my form was unimpressive on the track, where I was now in Swindon’s ‘B’ team in Southern Men’s League Division 3 (West): quite a fall from grace after running in the British League. During four attempts, I couldn’t beat 16:14 for 5,000 metres, although one of them was gold at the Scottish Masters in Dumfries. It was some compensation that I now held three Scottish titles at the same time: indoor, cross-country and track.

At the end of a short summer season I showed glimpses of good form. I ran 26:45 to win the Kintbury Five Miles on a hilly course with off-road sections; 15:52 for 5K road, an outright pb and much quicker than my best track time of the year; and a 4:17.4 1500 metres, which was one of my best ever age-graded performances.

A planned break would recharge me for the forthcoming cross-country campaign. Confident, uninjured and in good health, I was nevertheless cautious in setting my goals. I had enjoyed several months of uninterrupted training but had missed most of 2002 due to the hernia, all of the 2003 track season because of Achilles trouble and half of the 2003/2004 cross-country season. Could I stay healthy, regain selection for Scotland after an absence of two years, pick up where I left off and improve on fifth M45?

Training was going well. During a family holiday in Dorset I was up before everyone else and running along the beach and cliff tops. It was impossible to avoid steep hills, not that I had any intention of avoiding them: I targeted the steepest and ran repetitions, building strength-endurance. After each run, I would take our two Springer Spaniels down to the beach to swim. Someone must have taken a stunning photograph from the clifftops of me and my two canine training partners swimming in perfect formation, the early morning sun glinting off the calm surface of the sea.

We’d all spend the rest of the day doing normal holiday stuff, although I did sustain an unusual injury bodyboarding, when a freak wave flipped me over into hyperextension on the edge of a steep, pebbly beach. It was one of several niggles treated on the physiotherapy table, although nothing was severe enough to put me off training.

After that week away I kept doing the basics: long cross-country runs; tough sessions on the treadmill; sustained road runs up to ten miles, touching six minute miling pace; my favourite cross-country reps sessions. You could do reps anywhere: find a field or patch of woodland, preferably hilly, plan a loop that takes between three and six minutes to run hard around, get your first run done, rest, repeat and go again. The exact distance doesn’t matter as long as you run the same loop. As the season progressed I would add a rep or reduce the recovery and try to keep the times consistent, although times varied from session to session and course to course because of changes in the weather and conditions underfoot.

There was also a recovery swim and two or three climbing sessions every week. Focused weights training was bringing a new element to the strength-endurance fostered on the Dorset coast. There was a training method called Body for Life that we were promoting in the gym. The crux was that you could complete a quality session in around twenty minutes (plus warm-up and cool down), rather than wandering aimlessly from machine to machine. Leading by example as always, I was following the programme, making full use of free weights and cables.

My weekly mileage never exceeded fifty. Since becoming a veteran, something would always go wrong when I reached sixty miles and I would have to miss some training, unlike my younger days when I could just keep going. You shouldn’t look back and try to replicate your training from those days: you should work with what you have now and look forward. I didn’t repeat the sixty mile weeks but I didn’t regret having done them before. They were part of the journey that had brought me to the brink of achieving something. Not more than I ever thought possible, because I did think it was possible. But more than I had ever achieved before.

Because I had been selected again for the British & Irish.

And I was feeling more and more confident that this was going to be my year.

What caused this improved form and increased confidence? Well, good form and confidence feed off each other like spreading flames. But what had ignited the flames? There was no single spark. It was a combination of circumstances: the successful second half of the previous cross-country season, glimpses of good form in the summer, resting, a week of training in a different environment by the sea, several months of uninterrupted training, and a pledge to improve my nutrition.

Most athletes know what they should be eating, and nutrition training had increased my knowledge. However, it’s one thing to know, and another to do. As a club athlete you may need a selfish streak to achieve your goals, but living with your family, you can’t always run whenever it suits you or eat whatever you want. There must be compromises. I would never have dreamt of dictating to the family what they ate, but I could organise my own breakfast, snacks and packed meals for work. And I made a simple pledge not to eat sweets, biscuits or crisps. Some say that if you exercise a lot you can eat what you like, but it’s not true: you need good nutrition to fuel good training for good results. I still ate cake, though: you deserve some treats when you’re in full training.

There was also a career decision.

Working at the leisure centre had helped me get back on my feet after the stress that caused the end of my teaching career. I felt valued, comfortable and safe. But I needed a new challenge. I wanted to have some stress in my life again, so I started looking for another job. It would be stimulating and I could handle it. And with that realisation came the confidence to take on anything or anybody, including the best in my age group at international level.

*******

The first race of the season.

The Highclere multi-terrain 10K, on my old stomping ground near Newbury.

The phalanx of 300 runners tapers down to two abreast as we exit the wide meadow and file into a narrow lane bordered by lush trees.

Nobody seems to be doing anything, so I take the lead and open up a gap without really trying.

And not one of the 299 comes with me.

I’m clear and away. I’m feeling good, so I keep pushing.

In front of the castle, up and down hills, through woodland, on tarmac and along rough tracks.

It feels easy.

Puzzlingly easy. Why am I so far ahead?

Walking through the finish funnel, a gauntlet of well-wishers, parents, children, old friends from Newbury.

My winning margin is over a minute and a half, ahead of rivals who are usually much closer. On rough terrain, 33:19 is my third fastest 10K ever and half a minute quicker than my best on the track or road this year.

*******

One week later I ran an outright pb of 1:12:01 at the Bristol half marathon. I could see the time on the finish gantry, second by second, all the way down the straight, and I was trying really hard to make it 1:11:59. It wasn’t an outstanding time by the standards of masters who were road running specialists, but it was an achievement for me. It was only when I saw the photos and results afterwards that I realised that Nigel Gates, multiple champion on track and country, was shadowing me for miles, eventually finishing some distance behind. I guess he wasn’t taking it seriously, but it was another boost to my growing confidence.

Fast forward another fortnight, and my shoelace was undone and flapping about, with a kilometre to go in the South of England (senior) road relays at Aldershot. Conversely, I was far from undone or flapping. I overtook seventeen runners on leg four, beating my own best time on this course by a large margin. Amongst the masters, only two M40s and Nigel Gates ran faster.

When you’re in race shape, non-runners think you’re not well. Mum might say, ‘Are ye okay, son? Are ye eating enough? Ye’re looking awfy thin.’

But runners say, ‘You’re looking lean and mean. You’re on for a good run today.’

It takes one to know one, but here at the relays, a friend and rival said, ‘That’s a huge improvement all of a sudden. Are you sure you’re not on performance-enhancing drugs?’

No.

Never.

It was all honest endeavour.

I was well. Not one hundred percent well—I was being treated for various aches and pains—but who is ever 100% when training hard towards a major race? There’s a fine line between being very fit and being injured or ill, a line that I had crossed many times. It’s not unusual for an athlete to be teetering on the edge. But if you always train the same, you’ll always race the same. If you want to do better, if you want to win, you need to take risks. You might overdo it, get injured and miss some races, important races, maybe even whole seasons. But what’s better: a career full of consistently average performances, or one with injuries, illnesses, periods away from the sport you love but, at your very best—when you’ve planned meticulously and worked hard towards a peak—you achieve something far superior to anything before or since?

Something that you’ll never, ever forget.

*******

So that was a 10K multi-terrain race, a half marathon and a 6K road relay leg. All good. And I hadn’t run on my favourite surface yet. How would the first cross-country race of the season go?

The Wessex League opener.

Glastonbury.

I was rocking.

Like a lead guitarist ramping up the volume riff by riff, all the way to the final curtain.

Next gig, please.

The inaugural Swindon half marathon.

On a very hilly course, against the best road runners from Wiltshire and beyond.

Including Swindon’s own Matt O’Dowd, who ran for GB in the Olympic marathon that same summer.

*******

The roar of the crowd left behind in the town, we’ve run four miles and are heading for the first big climb, up Badbury Hill. Four of us in the leading group: Derek from Pewsey, my clubmates Nathan and of course Matt, and me. I was a bit worried about a sore throat but not now: what sore throat? I’m feeling fresh and full of confidence, so I take the lead.

I’m running along the top of the hill,

And everyone else is still climbing.

Seven miles gone, passing one of the radio cars reporting back to the announcer at the start/finish area.

‘It’s not Matt: it’s a much older runner, and he’s sprinting!’

It must be an optical illusion because I’m only striding downhill. And not that much older.

I’m nearly half a minute clear.

I’ve dropped Matt O’Dowd, Olympian!

What’s going on?

What’s going on is that Matt’s obviously taking it easy. He can overtake me whenever he likes.

But I can dream, can’t I?

Maybe, just this once,

The Olympian will have an off day,

And let me win.

The nine mile mark, another radio car.

‘He’s not the youngest of runners, you know. Isn’t he doing well for his age?’

The ageist remarks don’t offend me: I know I’m doing well. For any age. But I can hear breathing behind me, closer with every few strides.

Matt is waking up.

He’s going to pass me.

He draws level, makes an encouraging comment, which I return, and he’s away.

The next couple of miles are lonely until the noise of the crowd welcomes me back into town. I recognise some voices but don’t risk turning my head to acknowledge them. I’m in no danger of either catching Matt or being caught by anybody behind me but I’m on schedule for a pb: I can’t let myself be distracted now.

I’m pushing hard, uphill into Old Town. It’s tough, it’s painful but I’m loving it. The encouragement from the community thronging on both sides of the road drives me forward to the top of the hill, along level ground to the Croft roundabout, left into the downhill finish towards the Nationwide building. Sprinting, really sprinting down the final straight, under the gantry. A volunteer holds out a medal but she’s too close to the line. I’m still sprinting while holding out my hand but missing hers. When I finally come to a stop, I retrace my steps and walk back to her apologetically, nod a thanks for the medal. Someone thrusts a microphone in my face, and I realise that I’m too out of breath to say anything coherent yet. ‘In. A. Minute,’ I gasp.

Since re-entering town, the last couple of miles, about eleven minutes, have whizzed by. I’ve missed my pb by fourteen seconds, all on that final climb. But on a hilly course, finishing second behind an Olympian, it’s been a much better race than Bristol.

‘How did it feel,’ asks the man with the mike. ‘Leading Matt for so long?’

‘Surreal.’

Surreal indeed: the Olympian, the community, the atmosphere,

Most of all,

Yet another boost to my confidence.

What next?

*******

What next indeed. It was tempting to find a 10K, 10 miles or even another half marathon to see how fast I could run while in such good form. I settled for the Tewkesbury five miles three weeks later.

Two races before the British & Irish International Cross-Country Championship.

I could hardly wait.

It’s like another runner (a better one) has possessed my body.

Those were the clumsy notes in my training diary.

I’m going into open races believing that I’m going to win.