THE SCOTTISH MARATHON CHAMPIONSHIP

THE FIRST FOUR RACES

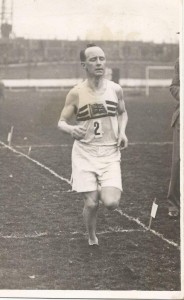

The start of the Fiery Cross Relay: Donald Robertson centre with Dunky Wright on his left

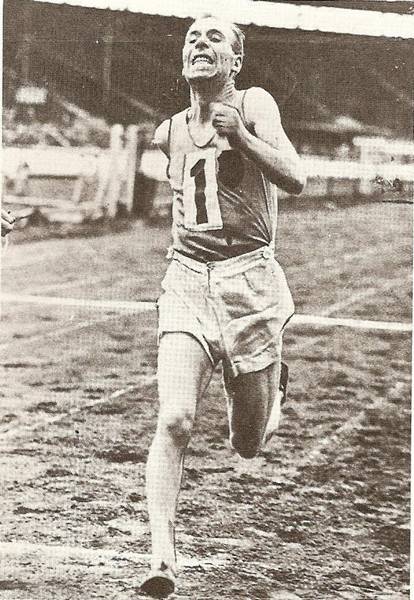

Who were the stars of Scottish marathon running before the Second World War? In 1932, Duncan McLeod Wright (born 1896) had finished a close fourth in the Los Angeles Olympics, and Donald McNab Robertson (born 1905) can be seen finishing seventh in the marathon in Leni Riefenstahl’s epic film about the 1936 Berlin Olympics. These two ‘giants’ of Scottish Athletics (in Dunky’s case, the description can only be metaphorical) finished first (Donald) and second in the inaugural Scottish Championship event in 1946. Third was Andrew Burnside, who ensured a Maryhill Harriers clean sweep, like the good team man he was. (Later, Andrew became a well-known race organiser.) Previously, in 1930, Dunky, whose race diet was rumoured to be brandy with raisins, had won a gold medal in the Empire Games in Hamilton, Ontario, beating Sam Ferris of England by half a mile to finish in 2.43.43. As well as that, he had captured two AAA titles; and Donald Robertson, famed for his finishing sprint, no fewer than six AAA titles as well as a silver medal in the 1934 London Empire Games. He won his first AAA championship wearing a pair of shoes from Woolworths which cost 1/11 halfpenny – not much cushioning there, then!

Dunky Wright

Undoubtedly the SAAA marathon championship was started because of pressure from the Scottish Marathon Club, which had been founded in 1944, to foster marathon running in Scotland. The SMC itself derived from a sequence of events before and during the war. In 1936 Dunky Wright, who had run in the three previous Olympic marathons, won one of the qualifying races to be used for selection purposes for Berlin. He was told that it would not be necessary to compete in the others to make the British team – but unfortunately he was not selected and decided to retire from competitive athletics.

When war started in 1939 he was appointed Sports Officer in a Home Guard Battalion and tried to find ways of keeping himself and others fit. He had contacts with people who raised money for the war effort and convinced them to include road races in their campaigns. ‘Muster runs’ attracted enthusiasts to cross country races in the winter and to road races in the summer. Unfortunately it was difficult for individual athletes to obtain clothing coupons to replace the thin sandshoes which running quickly wore out. However Dunky supplied many with army issue sandshoes; and Jimmy McNamara got hold of pads which were used to reinforce Fire Brigade helmets. These pads, if smeared with Vaseline to reduce friction and blistering, reduced destructive impact when sandshoe struck road. The friendship between such rugged pioneers led to the formation of the SMC.

That fascinating magazine ‘The Scots Athlete’ started in April 1946 and continued until May 1957. Walter Ross was the inspirational editor, and George Barber wrote well on marathons. Perhaps best of all were Jim Logan’s athletics articles and John Emmet Farrell’s detailed, knowledgeable ‘Running Commentary’. The first Scottish marathon championship took place on June 8th 1946, in conjunction with the Scottish Junior track and field championships at Meadowbank track, Edinburgh. The route was: Falkirk, Laurieston, Polmont, Maybury Road, Ferry Road, Pilrig, Easter Road and then into Meadowbank. Much of the credit for the ‘enthusiasm for road running at present’ was given to the personality and example of the famous ‘Dunky’. Donald Robertson wasn’t even demobilised yet but looked fit and, at 40 years of age, as a careful liver and keep-fit ‘faddist’ still rated as a probable Olympic competitor. Participants stripped in Falkirk Technical School and were conveyed by bus to Laurieston, where the race was started by the Provost of Falkirk. Seventeen runners started against a fairly heavy breeze. Neither Donald nor Dunky were too confident, since it had been many years since the tackled the full distance. However Dunky’s pace gradually dropped all the others apart from Donald, until the latter burst away up a stiff hill and won by about 200 yards in 2.45.39 from Dunky. Andrew Burnside moved up ten places during the last ten miles to finish third. ‘The winner was cheered loudly by the Meadowbank spectators.’ ‘Unplaced runners who finished the course are worthy of mention as the fact of covering the full distance was a feat in itself – W. Kennedy (Kilbarchan AAC), H. Duffie (Dumbarton AAC), R. Sime (Edinburgh Southern), J.E. Farrell (Maryhill Harriers), A. Gold (Garscube), P. Pandolphi (Maryhill Harriers) and R. Devon (Motherwell YMCA).’ A few well known future members of the Scottish Veterans there! The report finishes by commenting that, while refreshments, wet sponges, medical support and traffic control were all well organised, ‘surely arrangements could have been made to provide a nice meal for the runners after the race.’ ‘A mug of canteen tea and a bag of buns was not quite the thing. Catering facilities may have been difficult that day, but we peeped through a door in the Pavilion and saw fine tables set. Were the people invited to the spread more worthy of it than any of the runners? The pertinent question is not asked in any disparaging manner but in the spirit of fair play and with a thought for future races.’ Nevertheless ‘The first SAAA marathon championship will be remembered. It was a great occasion.’

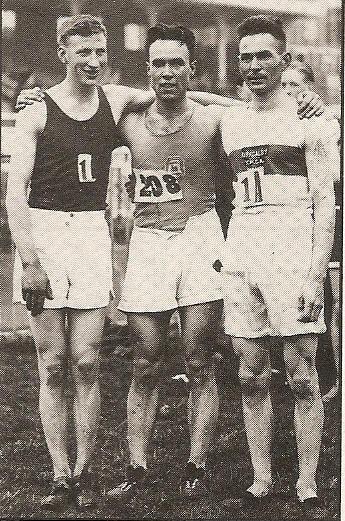

John Emmet Farrell, best known as a cross country champion – on that surface he seemed to ‘come alive’ – won the National in 1938 and 1948. However he took up the marathon ‘as a challenge and because of its romantic and historical past’. He remembered that the rules were stricter – drinks were only permitted at specific and well-spaced out intervals. Although finishing times seem slower than nowadays, Emmet pointed out that competitors were hard-working amateurs running in their spare time and without sponsorship. His Maryhill Harriers clubmates and friends, Dunky and Donald, were remembered as contrasting personalities. ‘Donald was quiet and modest but ambitious. A marathon runner only, he reached his standard by hard consistent work. Dunky was more of an extrovert. He was more talented and versatile – on track and cross country as well as road. Yet Dunky’s sense of humour was not universally appreciated!’

Gordon Porteous, a Scottish cross country international in 1946, was another Maryhill Harrier who continued to run amazingly fast for an ‘ultra-veteran’, even in his 90s. What diet did his club members follow to ensure such longevity and fitness? After the war the problems were digesting dried egg and getting hold of enough food to sustain them. Runners lucky enough to be ‘possibles’ for the 1948 Olympics received food parcels from South Africa, courtesy of the AAA! Survivors of the Saturday long run replenished reserves with Bovril (served in special club Bovril mugs) and cream crackers or a pie. Gordon remembered that Maryhill road men had one advantage over their rivals. Dunky was a member of the Home Guard – ‘Dad’s Army’ no less. (This was entirely suitable for the future broadcaster called ‘the Daddy of them all’ by Scottish Radio announcers introducing his Saturday evening athletics reports!) The crafty fellow obtained a supply of heavy brown Army plimsolls, which had much thicker rubber soles than the usual ones! More cushioning and fewer blisters. The alternative was Dunlop Green Flash – a tennis shoe which would ensure blood on the road for its masochistic owner. This brand was still used in the early 1960s!

Other kit comprised shorts, a vest, grey flannel trousers for the warm-up and a jersey with long sleeves to be pulled down over the hands on cold nights. Training was usually thirty miles a week. Maryhill Harriers (motto – ‘Good Fun – Good Fellowship – Good Health’) ran together from Maryhill Baths on Tuesdays and Thursdays – about seven miles a night. There might be a slow pack and a fast pack, each one with a Pacer and a Whip (self-explanatory). A good deal of wisecracking could be heard, especially as the fast pack whizzed past, unless runners were breathless. On Saturdays, if there was no race, a pack of runners might cover fifteen or even eighteen miles over road and country, followed by tea, buns and a sing-song to the music of mouth organs etc. An alternative was some serious hiking. Victoria Park AAC changed for their Saturday epic at the West of Scotland dry-cleaners in Milngavie! How did they remove the mud afterwards? John Emmet Farrell said that the National cross country distance of nine miles suited him because it seemed ‘a good balance of speed and stamina’. He didn’t mention that it was only half the distance he covered on Saturdays!

Not surprisingly, Sunday was considered the day of rest. However Dunky and Donald (who was considered ‘a bit of a horse’ by Gordon Porteous) added a long Sunday run to the regime. Donald McNab Robertson was reputed to be the first of the ‘hundred miles a week’ men, perhaps twenty mile runs up to four days a week, 25 on Saturday, and a thirty mile hike on Sunday; and Dunky certainly used to put in more ‘six-minute miles’ than most of his contemporaries. Gordon remembered that Dunky absolutely hated to be defeated in races, and was known for scoffing at opponents with satirical comments like ‘I could have beaten you with my shoelaces untied!’ (Not unlike Ian Binnie in the fifties and Alastair Wood in the sixties).

Donald Robertson winner of the first SAAA Championship

The second Scottish marathon championship, on 5th July 1947, resulted in another victory for the redoubtable Donald Robertson, in 2.37.49 – this time with a favourable wind – on a similar course to the previous year. The race was held in conjunction with the revived International between England, Scotland and Ireland. Donald went on to win the AAA title that year as well. Third place (2.56.05) went to a real enthusiast – the short-striding John (‘Jock’) Park of West Kilbride Harriers, who had dropped out in 1946. Thus he had the satisfaction of beating the standard times in both Scottish and British events, since he had finished a splendid 9th at the White City in 1946. He was an Ayrshire farmer who showed great determination by training consistently and doggedly on his own. Tragically he was destined to die from kidney disease at the age of 29 in August 1948, and ‘The Scots Athlete’ printed heartfelt tributes from many friends in running.

In second place (2.42.53) was John Emmet Farrell, who went to win a total of three silver and two bronze medals between 1947 and 1954, when he was 45 years old. He remembered that ‘he lost considerable distance over the last three or four miles, where Donald’s experience and stamina proved the deciding factor.’ This sounds like a familiar syndrome to anyone who raced Donalds Macgregor or Ritchie in later years! Emmet’s finest marathon however was the British (AAA) event during a Loughborough heatwave in 1947, when he finished fourth in 2 hours 39 minutes behind Jack Holden (2.33), Tom Richards (2.35) and Donald Robertson (2.37) – three well-known Olympic contenders. Richards, in fact, went on to win the silver medal in the 1948 Olympic Marathon.

Emmet Farrell (centre) after winning the national cross-country in 1938

In August 1947, 26 Scottish runners, including Dunky Wright, Donald Robertson and Charlie Robertson, took part in a unique event – The ‘Fiery Cross’ Edinburgh to London Relay Run. Photographs were supplied by one of the athletes – George Mitchell of Edinburgh Southern. Another participant was Walter Ross, the editor of ‘The Scots Athlete’.

Willie Carmichael was team manager and his article explains that the idea was to advertise the ‘Enterprise Scotland’ Exhibition. The team wore blue vests bearing the lion rampant and tracksuits boldly lettered ‘Scotland’. Thousands thronged Edinburgh Castle to witness the ceremony of lighting the crosses and extinguishing them in goats’ blood according to ancient custom. The skirling of the pipes added to a background of medieval and barbaric splendour. Donald Robertson received the first cross from the Lord Provost and all the runners accompanied him for three miles along the High Street and Princes Street and out of the city. Then he continued on his own to complete the 25 miles to Peebles, in two hours forty minutes!

There were no fewer than thirteen hand-over ceremonies with waving flags and pipe-music – in Peebles, Galashiels, Hawick, Newcastle, Darlington, Northallerton, York, Doncaster, East Retford, Newark, Grantham, Stamford, Biggleswade and the City of London.

The most stirring part of the journey was the last ten miles through London to the Guildhall. As in other sections of the run, timing was important – runners had to hurry up or slow down according to the schedule. In this case they arrived right on time, despite the fact that London traffic was not delayed to facilitate the runners’ progress. Dunky Wright had the honour of presenting the message from the Lord Provost of Edinburgh. Fiery Crosses were handed over, each bearing the flag of the country for which it was destined. Every runner stepped forward, held aloft his cross, and loudly proclaimed the name of the country to which it would be sent by aircraft.

Quite an event! A memorable eccentric journey covering 406 miles in 47 hours 31 minutes.

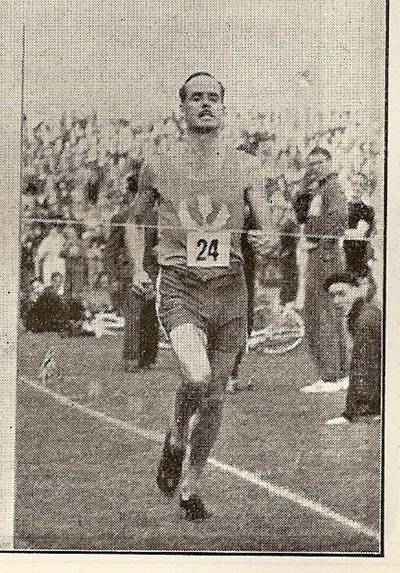

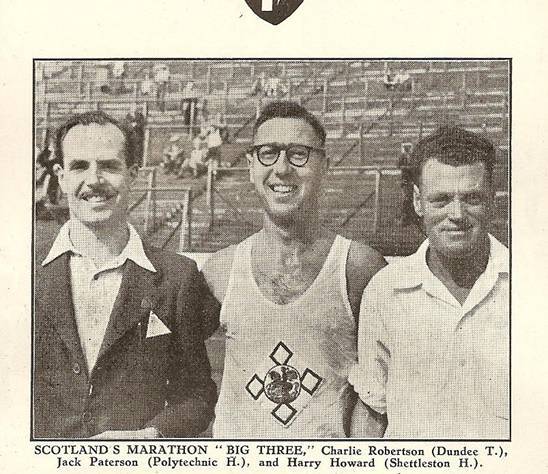

1948 saw the emergence of a new Scottish talent – Charlie (or ‘Chick’) Robertson (Dundee Thistle Harriers), an ex-major in the Black Watch, who was advised by Dunky Wright and whose running style was particularly elegant. Charlie won the Scottish Marathon in 1948 and 1952, as well as being squeezed into second place in 1950. Previously he had been a good cyclist and had made an immediate impact on turning to distance running in the 1947 Perth to Dundee 22 miles road race, when he was second, less than two minutes behind his record-breaking clan member Donald McNab Robertson. Charles (Chick) Haskett, father of well-known runners Christine and Charlie, remembered that era well. During the War, Dundee Hawkhill kept going, and joined up with Thistle athletes, since the Thistle club hut had been bombed out! Perth to Dundee was the big event – occasionally a full marathon. Chick used to sell race programmes along the route, while the competition was actually on. Training in Dundee was similar to the Glasgow pattern, only some runners went rambling in the hills on Sundays. Of course several athletes were religious – especially the famous cross-country champion John Suttie Smith. He was even a non-smoker! Charlie Robertson himself was a keen churchgoer and hill walker. Mr Haskett remembers that he designed jewellery, being an art teacher, and was conscientious – a hard trainer. Charlie wore a small neat moustache and had a normal build, with a heavy chest – not as skinny as many runners. He gave the impression of ‘being in control’.

Charlie Robertson winning the Edinburgh Marathon in 1951

This impression is emphasised by Gordon Porteous who actually competed on September 11th 1948 over the Perth to Dundee course (extended to full distance) during Charlie Robertson’s first success in the Scottish Marathon. Gordon wrote that ‘the first few miles wer wie rather sedate, there being a pack of six or seven runners, yours truly amongst them, none of whom wanted to take the pace, till Charlie decided to go at about five miles.’ The break was clean and Charlie (2.45.12) won by over three minutes from John Emmet Farrell.

Third in that 1948 championship, a young interloper from Edinburgh Southern Harriers, was Bob Sime, who felt like ‘a wee boy’ compared to the famous Farrell, (who described Bob in ‘The Scots Athlete’ as running ‘a remarkably fine and gallant race though desperately tired at the finish.’) However Bob remembers that (once Charlie Robertson was out of sight) he was running along with Emmet on a quiet part of the route when they passed a parked van and the driver called out, ‘Come on, Farrell!’ And then, ‘Come on, Sime!’ Bob was pleased to be recognised (probably because of one of Chick Haskett’s programmes) and admired Emmet’s sporting spirit when he confided, ‘That was my son.’ After the race, Bob Sime felt absolutely ‘jiggered’ and sick, especially after a ‘helpful’ first-aid man gave him something unpalatable. Dehydrated on the train home, he remembers lying slumped in a corner, sipping a flagon of iron brew, and worrying about what fellow passengers might think of him. Yet Bob was very pleased with his third place, since it was his first time near a medal. Unfortunately medals were presented only to the first two! But justice was done when ESH presented a special cup to young Bob. His club used to train from the Liberal Club in Buccleuch Place, running a route which took them through the Meadows and down Lovers’ Lane. On one occasion, running from Liberton towards Lasswade on a snowbound Saturday, the pack of runners combined to lift a lady’s trapped car right out of a ditch, before continuing their training – naturally. Sundays for Bob might mean a twenty mile walk in the hills, just to stretch the legs!

Charlie Robertson receives several honourable mentions in John Emmet Farrell’s excellent book ‘The Universe is Mine’. Charlie had two valiant attempts to make the Olympics. In the 1948 trial he led narrowly at twenty miles but was forced to retire at 23 miles ‘when his legs gave out’. The winner Jack Holden, later gold medallist in both the European in Brussels and the New Zealand Empire Games in 1950, admitted that ‘Robertson had him worried for a time’. Then in the 1952 trial, Charlie finished fourth, only one place off the team, in his best time of 2.30.48 – a gallant performance. John Emmet commented that when Charlie won that year’s Scottish Marathon, his time was 2.38.07 – so either the ‘Polytechnic’ Windsor to Chiswick course was faster, or the importance of the trial made runners try even harder. Other finishers in the 1952 Scottish event, all past or future notables, were J. Duffy (2nd –2.38.32), J.E. Farrell (3rd – 2.40.54), J. Paterson (4th – 2.41.28) and J. McGhee (5th – 2.44.46).

Everyone was shocked by the sudden death, from thrombosis, on 15th June 1949, of Donald McNab Robertson, who was 43 years old. He had been training well for the Marathon championship and had finished only a few seconds behind Tom Richards, the 1948 Olympic silver medallist, in the 20 mile race from Greenock to Ibrox on May 21st. Brian McAusland has written that Donald was ‘an ideal figure to hold out to youngsters as an example – modest, unassuming, dedicated and, although naturally proud of all that he had done, not boastful at all. He had made himself what he was by hard work and was a real credit to himself, to his club and to Scotland’. ‘The Scots Athlete’ article said ‘Donald, by virtue of his courageous spirit, the charm of his modesty, and the warmth of his smile and his friendship, endeared himself to every sports-follower in the country. He was a loved figure in Scottish athletics….Words fail to express the sorrow at his passing. He was good in every way. We bow our heads in deep and grateful remembrance.’

In 1949 over the Gourock to Ibrox course on a blisteringly hot day in July, the winner was 36 year old Jack Paterson from Polytechnic Harriers, who had been an excellent 4th in the famous Poly marathon earlier that year. He also won the Scottish championship in 1951. In 1949 the runner up was from England, too – James McDonald (Thames Valley Harriers). Third was Harry Haughie, a Springburn Harriers stalwart who later emigrated to Australia.

According to Jack Paterson in ‘The Scots Athlete’ it was the sporting James McDonald who had ensured a) that after the Poly race Paterson knew about the existence of the Scottish event and b) that he himself would not finish first! After establishing what looked like a winning lead, Charlie Robertson the holder had to retire from the race with blisters and Paterson defeated McDonald by only four seconds (2.57.07 to 2.57.11). ‘This after he had nursed and advised me for the last 16 miles of the race. Truly a great sportsman and the gamest of runners!’

The victor enjoyed a good season’s running, which displayed his great enthusiasm, grim determination and resilience, based on long slow distance training as suggested by Arthur Newton, the great ultra distance champion. He was most consistent, finishing 6th in the AAA Championship, but perhaps his best race was in September when he won the City of Edinburgh Marathon in 2.46.04, defeating in another sprint finish by five seconds Cecil Ballard, a well-known English athlete. In February 1950, Jack Paterson went on to represent Scotland in the Empire Games in Auckland, New Zealand.

[ Introduction ] [ First Four Races ] [ The Fifties ] [ The Sixties ]