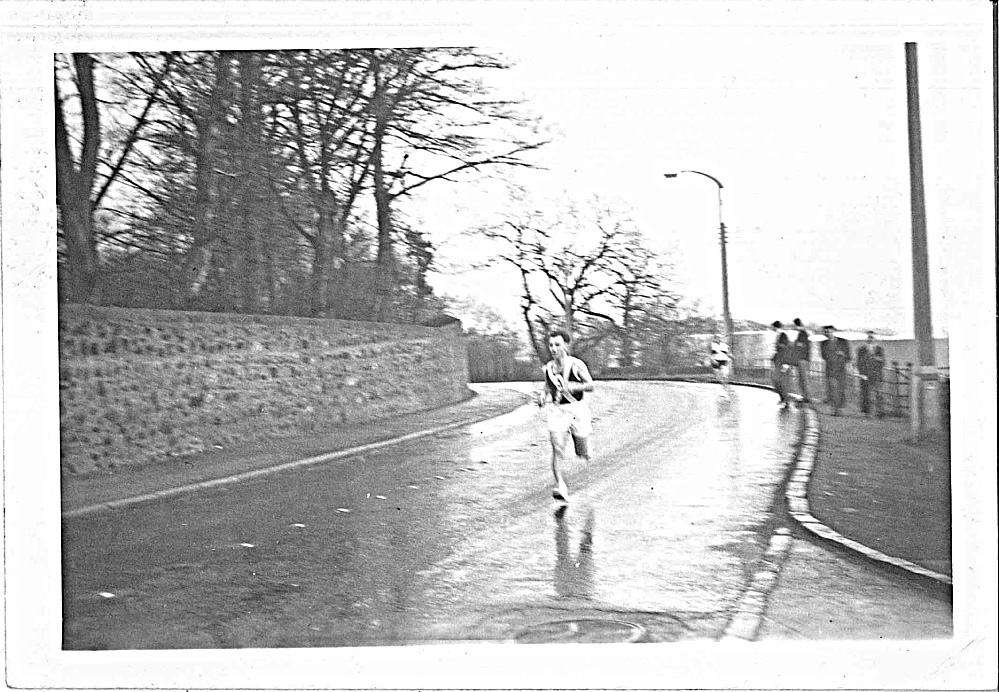

Harry Howard (21) and Charlie Robertson in the Perth to Dundee

On 8th July 1950 the Scottish Marathon Championship finished at Meadowbank in Edinburgh once again. ‘The most coveted honour in long distance racing’ was gained by 36 year old Harry Howard from Kilmarnock, representing Shettleston Harriers. By a margin of only 13 seconds he defeated Charlie Robertson of Dundee Thistle. Howard’s time was 2.43.56. Evergreen Emmet Farrell was third in 2.48.24. Jack Paterson could finish no better than 6th in 2.57. Hugh Mitchell remembered his clubmate Harry Howard as a particularly hard man who used to roll in the snow after cross-country races!

Charlie Robertson was fit enough in August to break the record for the famous Perth to Dundee 22 mile race, but for Scottish runners, 1950 was Harry Howard’s year. He went on to win the other Scottish marathon at Edinburgh Highland Games in September, defeating Farrell and future Olympian Geoff Iden of England, in 2.40.10. Howard had also finished a brilliant 3rd in the AAA Marathon Championships. In previous years he had raced successfully on the road and sometimes cross-country, starting his career in the Army – as a boxer before he turned to running. Emmet Farrell remembered his ‘pillar to post’ style of running and considers him to have been ‘a tough little character’. Long road races for which he held records included Glasgow to Hamilton 13, Kilbarchan 14, and Carluke to Lanark and back 12. Anyone remember those? In 1946 Harry Howard showed versatility by winning a Scottish cross-country vest at Ayr Racecourse after the 9 mile ‘National’. Overall, deserved success for a dedicated and persevering athlete.

The English sportsman of the year (for all sports, not just athletics) was of course Jack Holden (Tipton Harriers), 43 years young, and the winner of five marathons in 1950, including the Commonwealth and European Championship events. In Auckland (2.32.57) he battled through three terrific thunderstorms and finished the last ten miles shoeless, with blistered feet. In Brussels he had a real battle with Karvonen of Finland and Vanin of Russia, eventually winning by half a minute in 2.32.13. The AAA was won in 2.31.03 and he also finished first in the Midland and Poly races. And all this two years after failure in the Olympic marathon which he probably lost because he trained too thoroughly. He pickled his feet in permanganate of potash until they were like leather. After he had run eight miles, blisters formed under the outer skin which was so tough it couldn’t be broken. Having struggled on to the limit of human endurance even he had to give up. But how he fought his way back to glory in 1950!

Held with the SAAA Track and Field Championships for the first time, the 1951 Scottish Marathon, from Symington to Hampden Park on June 23rd, was very humid, and a number of the more prominent runners had to drop out due to heat exhaustion, including the extrovert Willie Gallacher (Vale of Leven) who was notable for having his own coach and publicist. Other casualties were J.E.Farrell and Alex McLean (Greenock Glenpark Harriers). Gordon Porteous ended up fifth. One notable phenomenon is that Gordon’s time was 2.51.11, just 24 seconds faster than his superb run (almost a marathon of years later) in the 1975 Scottish Marathon – a deterioration of only one second a year! Jack Paterson would have enjoyed that statistic – Emmet remembered him as having a prodigious memory for times and facts about running.

A hard man to beat in tough conditions, it was Jack Paterson who won for the second time (2.43.21) from A. (Willie?) Arbuckle of Monkland Harriers (2.47.42) and J. (Duncan?) Bell from Kirkcaldy Y.M. (2.50.38).

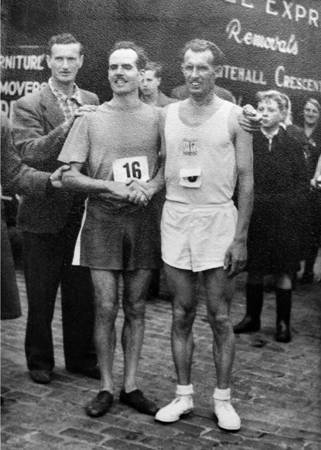

Charlie Robertson had been training more for shorter road races and had also achieved third place, his highest position, in the National Cross-Country Championships. However he produced a really excellent run to break his own record and defeat Harry Howard in the Perth to Dundee 22; and ran even better to achieve a famous victory two weeks later in the Edinburgh Marathon. In the latter race Robertson and Howard missed the start and joined in after the first lap of the track – faced with the prospect of running an extra lap at the end of the marathon! The quality of the field was almost unparalleled: not only all the best Scots but two good Englishmen. After a very competitive struggle Charlie Robertson managed to catch and overtake Harry Howard and run strongly to the park, complete his extra lap, and win by eighteen seconds (2.38.15) from J.W.Stone of the RAF. Harry Howard was third (2.40.50), Jack Paterson 4th (2.41.59) and these were followed by A. Kidd (Garscube), Joe McGhee (St.Modans), J.Bell (Kirkcaldy), J.E.Farrell, J.W.Winfield (Derby) and young Andy Brown (Motherwell YM). In winning the battle of the Scottish Marathon Champions, Charlie Robertson produced his best performance to date.

In March 1952 ‘The Scots Athlete’ featured an article by G.S.Barber on Charlie Robertson. It starts ‘Here is an athlete who has studied all angles of the running game and found health and joy in it.’ A family man, he had two boys and two girls and was a keen gardener (fruit and vegetables) in his spare time. As well as detailing his many successes, the article comments on Charlie, the man who became a well-respected captain of the Scottish team in the 1952 International Cross-Country. ‘Charlie adopts common sense and a fresh approach …has his own ideas and says that every man should work out his own requirements and methods and apply them diligently and conscientiously.’ Variety in training was important to him but he believed in distance work. ‘If you train for stamina, speed will come.’ In marathons he thought that one should run one’s own race, ignoring others. He was a strict non-smoker and teetotaller. His pre-race meal was scrambled eggs with toast followed by cereal with honey and milk, taken two hours before a marathon. Hard work was the secret of his success. Amusingly, a photograph is also mentioned of Charlie ‘training for a marathon with his wife and kiddy accompanying him by bicycle and his dog trotting by his side’ – not his usual method perhaps.

The AAA Marathon and Olympic trial over the Windsor to Chiswick course on June 14th 1952 was ‘the fantastic marathon’ in which Jim Peters finished in a world best time of 2.20.42. He went out very fast, followed at a distance by Stan Cox and then by Geoff Iden. These three established a widening gap on the others. Charlie Robertson was determined not to start too fast in order to finish strongly. This tactic worked well, but the first three were simply too strong and speedy on the day. However Charlie was a valiant fourth and unlucky not to make the team for Helsinki. In fact his time of 2.30.48 had only been beaten once before in Britain and was the fastest time ever returned by a Scot. 8th was Anglo-Scot John.Duffy (Hadleigh Olympiads), Broxburn born and bred, in 2.36.35. Alex Kidd (Garscube) ran 2.38.39 and Joe McGhee (St Modans) 2.39.29.

Charlie Robertson with Jock Duffy

Charlie Robertson with Jock Duffy

After Emil Zatopek’s marvellous triple victory in the Olympics, finishing with the marathon in 2.23 – Jim Peters dropped out after trying to burn the Czech off – the Scottish Marathon on August 9th must have seemed an anti-climax. Once again, the course was the lengthened Perth to Dundee one – and there could only be one victor in his best year – Charlie Robertson, the winner of the inaugural D. McNab Robertson Memorial Trophy for best performance in Scottish road racing. However he had a serious rival in the John Duffy. The Broxburn man, who had served in the Army from 1940-45, and had shown immediate talent for running, and also for boxing, had settled in Southend, Essex, in 1946. Having put on two stones in weight, he started road running with his local club in 1947, eventually building up by cross-country and distance training. He had been second to his friend Jim Peters in the Essex 20, and had then won the race the following year before doing so well in the Polytechnic Marathon from Windsor to Chiswick. The Scots runners he had met there encouraged him to travel north for the Scottish Marathon.

Joe McGhee challenged earlier on in the 1952 race, but by fifteen miles it was a two-man affair with Robertson trying to bridge a 23 second gap to the leader Duffy. By 24 miles Charlie had a hundred yards lead, but then he felt cramp and had to stop and touch his toes before sprinting off and then stopping again! Still he finished with 25 seconds in hand (2.38.07) from Duffy, with Emmet Farrell third and then Jack Paterson, Joe McGhee, Alex Kidd, Andy Brown and Harry Haughie – some well-known warriors there. A fine finish to a glorious year for Charlie Robertson of Dundee Thistle.

1953 was to see Charlie Robertson fading from the running scheme – because of business commitments he was unable to train properly – and he must have been sad that a runner from Leeds, Eric Smith (winning narrowly from Joe McGhee) broke his record in the Perth to Dundee 22 by 28 seconds. But that is the way of athletics – everyone can hope to reach a peak, but records will always be broken eventually.

Another runner to start showing considerable promise was Harry Fenion of Bellahouston Harriers. John Emmet Farrell describes him as ‘pint-sized but with immeasurable pluck and tenacity’ and having ‘come right back to form after a spell in the wilderness’ to show himself ‘a sound classy runner’. Four years were to pass before Harry reached his best.

Two months before the Perth to Dundee classic, the Scottish Marathon Championship had taken place on 27th June 1953 on the old Lauriston to New Meadowbank course, finishing during the SAAA Track and Field Championships. The road race developed into an exciting scrap between the former Scottish ten mile champion Alex McLean (Greenock Glenpark AC), Joe McGhee (St Modans) and John Duffy from Broxburn and Hadleigh Olympiads. McLean took the lead after 18 miles and had 49 seconds on Duffy by 20 miles. By 24 miles this was increased to 68 seconds, and 33 year old Duffy was resigned to finishing second again. However ‘the knock’ (Fifties equivalent of ‘the wall’) intervened and poor Alex McLean was forced to walk until caught by Duffy. Then they both ran the last mile but the Army runner proved stronger, winning in 2.38.00 by 43 seconds. Joe McGhee showed obvious potential by finishing faster than the others and was only 62 seconds down on the winner. A disappointed McLean admitted his lack of long distance training, but the exhausted John Duffy had shown real guts in running himself out to the tape and he fully deserved his Championship victory.

John Duffy, born in 1919, was known as ‘Jock’ in his childhood, and inevitably during his years in the Army and in Essex, but as John to his family. He was a bricklayer and later a builder, and his hard physical work tired him for running – unlike Jim Peters, who was an optician. Nevertheless, John trained every day, sometimes running home from the building site, which could be up to fifteen miles away, and then making the return journey in the morning. On Sunday early he tried to cover fifteen to twenty miles, so that he could have a day and a half to recover before Monday evening’s run. The weekly total was between eighty and ninety miles. In the final stretch of a marathon, his strength usually enabled a fast finish. His wife complained about his training, although later ironically, when she realised how much money could be made in 1980s events like the London Marathon, she commented that she wished John could have won prizes like those!

Before his 1953 victory, John Duffy, his wife and two children, had taken the train from Southend to London, and then the ‘Starlight Express’ to Scotland – a twelve hour journey. Reaching Broxburn at 3 a.m., he had snatched a few hours sleep before his father arranged for an ex-Hibernian footballer to give him a rub-down. Then it was off to Falkirk for the marathon start. Dunky Wright apparently wrote in the newspaper that ‘Duffy always looked tired.’ No wonder! John remembered Alex McLean’s drive for victory, but although the gap widened, he just kept on trying hard, until he could see the leader struggling, and caught him with a mile to go. Sportingly, Alex said, ‘Good luck to you, mate’ as John went past. Duffy’s parents and brothers were waiting in Meadowbank stadium when it was announced that Alex McLean was about to win the marathon – and then John came in, triumphant.

Fourth was Alex Kidd, fifth D.Bowman of Clydesdale, sixth T.Phelan of Springburn and seventh Hamish Robertson of Edinburgh Southern Harriers in 2.53.18.

By the beginning of the 1953-1954 cross-country season, Joe McGhee had left St Modans AAC and had joined Shettleston Harriers, one of the two top clubs in Scotland. He was also benefiting from training done in the RAF and coaching by Allan Scally. In the 1954 ‘National’ he helped his team to win the title and gained his first Scottish vest after finishing seventh.

John Duffy was disappointed when, before the Scottish Marathon, only Joe McGhee, who he had beaten three times over the classic distance, was nominated for the Commonwealth Games team. Jim Peters even wrote the SAAA on behalf of the 1953 champion. However before the start, Dunky Wright informed John that the committee was not satisfied with the Scottish event as a trial, and said that if he wanted to be considered for a place in the team, he would have to do well once more in the ‘Poly’. This made it very difficult to run with conviction in the Scottish race. Rather a shame for Scotland, because John Duffy, who knew his English rivals so well, reckoned he had a chance of third place in the Commonwealth race, although he did not drink water either in training or in a marathon, unless he was having a bad time.

Joe McGhee’s fitness just kept on improving, and he took part in the Scottish Marathon Championship on 29th May 1954, over a new course from the Cloch Lighthouse, Gourock to Ibrox Park, where the Glasgow Highland Games were being held. The time at five miles, after a fast start, was 27.11, with John Duffy the holder, McGhee, Hamilton Lawrence of Teviotdale Harriers and George King of Greenock Wellpark all together. Also taking part were Willie Gallagher of Shettleston, John Emmet Farrell , Gordon Porteous and Eddie Campbell (St Mary’s), the famous Ben Nevis runner – but due to the warm day and very stiff headwind, only Farrell finished. Lawrence broke away, taking McGhee in his slipstream. After 15 miles and the long climb up from Langbank, Joe took the lead and Lawrence dropped out, saying he felt sick and had eaten nothing since breakfast. Not surprisingly, since he had not been given a chance of Commonwealth qualification, Duffy stopped too. Yet McGhee pushed on, covering the next five windy miles in 30.36 – good going on his own. While many participants were forced to drop out, Joe ran on as if closely pursued and won in the excellent Championship record of 2.35.22. Forty-five year old Emmet Farrell finished strongly in 2.43.08, with a tired George King, who had run the entire second half on his own, just holding off N.Neilson of Springburn Harriers by five seconds in 2.47.04.

George Barber, the journalist for ‘The Scots Athlete’ bemoaned the fact that the officials made no effort to clear the track for the marathon men or to announce Joe McGhee’s splendid performance. He wrote ‘Only those who have seen these men the whole way fighting every inch of the distance can understand their disappointment at the lack of interest shown by officials in the park when they finally reach their goal.’ Maybe marathoners don’t care much about crowds and officials – they’re just happy to stop running! However Joe’s next marathon would not be short of attention!

The British Empire Games were held in Vancouver, Canada, between July 31st and August 7th. Undoubtedly the marathon was even more memorable than the mile, in which Roger Bannister of England outsprinted John Landy of Australia in 3.58.8. Unfortunately the longer race is notorious rather than famous – for the sight of poor Jim Peters, badly affected by sunstroke and his own headstrong pace, staggering and collapsing short of the finish. Yet the statistics prove that the winner and gold medallist was Joe McGhee of Scotland in 2.39.36, from South African Jackie Mekler, the famous ultra runner, in 2.40.57 and J.J.Barnard, also of South Africa, in 2.51.49. There were only six finishers.

John Emmet Farrell stated that ‘Considering the gruelling almost freak conditions in which the race was run, the Scottish champion may have been said to have run the race of his life…..A race is never won or lost until the tape is broken or the finishing line is crossed……Judgement as well as pure running ability is an essential ingredient.’ Yet Jim Peters did not know that his old rival Stan Cox had retired (eventually suffering from sunstroke and running into a post two miles from the finish), and pushed on hard to the stadium instead of easing back.

George Barber blames officials once again. Not only did they allow the race to be run at a ridiculous time of the day – starting at noon on a scorching Canadian summer day, but once again chaos reigned in the stadium when it became quite apparent that the actual finish line was uncertain – the track event finish was short of the marathon one. Indeed Mick Mays, the England team masseur who caught Peters on the track, did so at what he thought to be the right line – Peters in fact could not have run on because an official had stopped him. Arthur Newton, former Comrades marathon champion, was very scathing about ‘the complete ignorance of the authorities about marathon running’, complaining that the race should never have been planned for the middle of a warm summer’s day and about the lack of sponges and water for cooling and drinking except at strictly limited drink stations. Years later Jim Peters himself said that, he may have fallen down twelve times on the track, but if he had only drunk more water he might not have fallen down at all.

In conclusion there is no doubt that, although it was a pity that Jim Peters retired from running shortly afterwards, Joe McGhee was very unlucky not to get all the praise he undoubtedly deserved for running such a brave, intelligent and determined race. ‘The Scots Athlete’ published photographs of him finishing strongly for a sensational win; and later standing proudly on the victor’s dais as the band played ‘Scots Wha Hae’.

The well-known sports commentator, Kenneth Wolstenholme, stated ‘Joe McGhee is one of those quiet, modest sportsmen who deserve all the success they can possibly win.’

In the 1954 Edinburgh to Glasgow relay, Victoria Park won for the fifth successive time, partly due to a splendid run by Ian Binnie on the long sixth stage. He chased down Joe McGhee of Shettleston, who had started 1.16 in front, and passed him just before the changeover. On the day, McGhee was second fastest and only 30 seconds outside the record, but Binnie broke the record by 49 seconds to record 32.32.

The results of the ‘National’ cross-country of 1955 were printed in the April edition of ‘The Scots Athlete’, which started with a personal message of good wishes from no less than Paavo Nurmi! In the championship, Joe McGhee gained revenge on Ian Binnie, beating him for third place by 22 seconds, to finish only nine seconds behind the surprise winner Donald Henson of Victoria Park. Shettleston retained the team title, however, helped by ‘the much improved and conscientious’ Hugo Fox, future marathon man, in 19th position. Harry Fenion was 16th.

By the time that the Scottish Marathon came round again, on 25th June 1955 over the Falkirk to Edinburgh course, Joe McGhee was even fitter than ever, ready to show that he was a worthy Empire Games champion, as well as supreme in Scotland. Emmet Farrell, himself 6th in 2.48.44 wrote that ‘Joe McGhee’s record-breaking 2.25.50 was easily the feat of the SAAA Championships, and puts him into world class and an extra glitter on his British Empire gold medal. Conditions were excellent but the course is by no means an easy one and this enhances the performance of George King (Greenock Wellpark Harriers) whose time of 2.34.30 beat the previous best ever in Scotland and that of Hugo Fox with a 2.37.35’.

George King (13), Joe McGhee (1), Hugo Fox (6)

George King had made his marathon debut the previous year, winning bronze despite a light training schedule of three sessions a week totalling 23 miles! Like most others at the time, he wore Green Flash tennis shoes, which were extremely heavy (especially when wet) but gave little protection. From March 1955, however, he increased his training load dramatically to over eighty miles per week! (Monday 14; Tuesday 5 + 10; Thursday 5 + 12 fartlek; Saturday 20; Sunday 15). Not surprisingly he felt strong in the 1955 Championship! Later that year George won a one hour race at the famous Ibrox Sports, covering 10 miles 1625 yards. Then he finished third in the Edinburgh Highland Games Marathon to Eddie Kirkup of Rotherham and Jackie Mekler from South Africa. The route was: Murrayfield, Corstorphine, Granton, Leith, Portobello, Morningside and back to Murrayfield.

Earlier in Joe McGhee’s record-breaking Scottish Marathon, W. McFarlane of Shettleston had been 4th in 2.43.27 and Hamish Robertson of ESH 5th in 2.46.58. The final two standard medal winners (for breaking three hours) in 14th and 15th were Eddie Campbell and Jackie Foster of ESH.

Jackie related that Hamish ‘took him in hand’ for this, Jackie’s first marathon. That morning they went to Woolworth’s where Hamish purchased a pair of black gym shoes – ‘the type worn by Brownies at the time, with a brown gristle rubber sole, costing five shillings a pair.’ Hamish was almost running in bare feet – years before Abebe Bikila !

In a very long interesting letter, Jackie wrote that ‘to run a marathon in the fifties, one was considered a) a god and b) a nutter’! He remembered being bussed (runners, officials, trestle tables and water) to the start at ‘Cemetery Brae’. The single bus dropped off officials and water station equipment on the way out. About one or two dozen runners took part in an average year. When the starter forgot to bring the race numbers, he said it would be okay to run without them, since he knew all the competitors’ names! The same bus followed the last runner, collecting officials, tables and drop-outs en route. Strugglers were encouraged to give up and get into the bus – so that it would arrive at Meadowbank in time for the officials’ tea! Spectators tended to laugh loudly at the sight of grown men in vests and shorts, staggering through Leith at 24 miles, often having to ask directions from passers-by. Yet Jackie remembered the warm applause at the end (apart from one year when he ‘threw-up’ in the finishing straight) and considers that the five shilling entry fee (including bus, a high tea for the stronger of stomach, and a good bronze standard medal for breaking three hours) was a much better bargain than mass marathon entry prices nowadays. However this 1955 event had one unhappy memory for Jackie. When he returned to his RAF base in England, he was hospitalised for a week and had several toenails removed. His medical officer warned him that, if he reported in such a condition again, he would be put on a charge, since it was Jackie’s duty to look after his body for the Queen! The same officer advised him to stop running, since by the time he was 40 he would have the legs of a 70 year-old! In his mid-sixties, Jackie completed ultra-distance races.

Unfortunately Joe McGhee was unable to run in the AAA marathon because of leg strain and had to retire in the Edinburgh marathon but he did achieve fast times in shorter road races – including breaking the record in the four and three quarter mile Nigel Barge event as well as his wonderful performance in the Scottish Championships. And he had great satisfaction in playing his part in the Shettleston team which won the 1955 Edinburgh to Glasgow road relay in a new record time.

By April 1956, a strong rival for Joe McGhee had announced his excellent form on the roads. Harry Fenion of Bellahouston, with his ‘very easy choppy stride’ broke the course record in the Clydebank to Helensburgh 16, beating George King of Greenock Wellpark by one and a half minutes. Yet when it came to the Scottish Marathon Championship, which was held in conjunction with the SAAA Athletics Championships at Meadowbank, it was Joe McGhee who won the title for the third successive year. As Emmet Farrell wrote ‘This was a record sequence and at the same time revealed a successful come-back after doubts occasioned by injury.’ His 2.33.36 was a meritorious performance in warm sultry conditions. The pace was fast right up to the twenty mile mark, which resulted in Joe slowing down considerably during the last few weary miles. George King had a leg injury and had to retire at halfway; Harry Fenion kept up with McGhee for a long time but had to give up at twenty-three miles, due to blistered feet and lack of experience. Alex Kidd of Garscube ran a sound race to finish second in 2.46.58 – a time worth much faster in normal conditions. Third was W. McFarlane of Shettleston in 3.00.18, slower than the standard (designed for cooler days) of 2.55. D.N.Anderson of Greenock Wellpark (3.00.42), M.W.Innes of Braidburn AC (3.02.48, Jackie Foster of Edinburgh Southern Harriers (3.07.4), I.C.Grainger (ESH) and P.Taylor (Dundee Thistle Harriers) also finished this particularly gruelling test.

George King related that in July 1956 he travelled with Joe McGhee to the British Marathon Championships at Birkenhead. Joe had arranged for a taxi, sponsored by the Daily Record, to drive them around the course the evening before the race – but torrential rain, thunder and lightning forced them to abandon that plan. Race day was very hot and sunny. Both Scots felt good, but the temperature continued to rise. Joe had to retire and George too was suffering from dehydration. He passed a young boy carrying a jar of water and asked him for a drink. The boy refused as it had taken him all afternoon to catch the minnows he was taking home in the jar! Poor George retired at half distance.

‘The Scots Athlete’ was falling on hard times by late 1956 – it was difficult to keep it going as a commercial concern – but the quality of writing was as good as ever. Particularly delightful was a piece by Emmet Farrell on the ‘physical and mental tonic’ of training over the country. ‘These easy enjoyable runs act as a gentle massage through increased circulation and the restraint in pace builds up nervous energy for the morrow – providing that feeling of athletic silk commonly known as ‘rarin to go’ …………in autumn with the air clean keen and crisp ….It is good too to look up into the sky occasionally and feel its vastness – a vastness which may put our day to day irritations into correct perspective…If you keep your eyes ever rooted to the ground you may occasionally pick up a threepenny bit …But you’ll never see a sunset or a rainbow!’ Long, slow distance running never had such an advocate!

The 1956 Melbourne Olympic Marathon was won by Alain Mimoun, the Algerian representing France, who had won several silver medals on the track behind the redoubtable Emil Zatopek. This time the great man was 6th but no one could grudge Mimoun, an International Cross-country Champion, his Olympic gold.

Harry Fenion in the E-G

The sensation of the 1957 ‘National’ Cross-country Championships was the victory of Harry Fenion of Bellahouston Harriers. ‘Harry, Youth champion in 1948, finds himself nine years later the senior king-pin. Everything went right for him and when he elected to go away at six miles no one could hold him. His pace uphill and downhill was devastating and completely demoralised the field. Small, but neatly and compactly built, his running on this occasion reminded (Emmet Farrell) of an old poem remembered from schooldays :

‘Up the airy mountain,

Down the rushy glen,

We daren’t go a-huntin’

For fear of little men.’

Harry Fenion was reported to be keen to add the marathon title to this splendid cross-country performance. He went on to repeat his previous year’s first place in the Clydebank to Helensburgh 16, narrowly beating Andy Brown of Motherwell. Since there was some uncertainty regarding Joe McGhee, Harry was installed as favourite to win the Scottish Marathon.

The 1957 race took place on the 22nd of June, finishing once again at New Meadowbank stadium in Edinburgh – and Harry Fenion (Bellahouston Harriers) did indeed achieve his ambition and became the only runner in history to win both the Scottish Marathon and Cross-country Championships in a single year.

He wrote that several well-known runners took part, including Ronnie Kane, George King, Andy Fleming, Hamish Robertson, John Kerr, Hugo Fox and Emmet Farrell. The training Harry Fenion did was rigorous. “I usually averaged 130 miles per week which included running three times a day, gradually adapting myself to run 5.30 per mile, which was race pace. This was done with the help of my friend who came along on his bike. He used to time each mile which was good because I was able to increase the pace and then settle back to a steady 5.30. The longest run I ever did was 33 miles. Most of my runs were 20 miles which usually included fartlek sessions. All this training was done in the morning at 7 a.m. before starting work, then at lunchtime and then in the evening. During training sessions I never ever drank any fluids. My diet included at least three steaks per week, one of which was eaten two hours before a race. I usually wore ordinary black sand-shoes from Woolworth’s and put a Boot’s the Chemist insole in them. They did not last very long as the roads were very rough where I trained.”

“The weather for the race was cold, mainly dry and at times wet – ideal conditions. For the first ten miles I sat in the pack watching everybody. Shortly afterwards I kept asking where the next drinking station was, making out that I was desperate to take water on board which I wasn’t – this was part of my race tactics. When we approached the watering station the other runners moved over to get a drink, expecting me to do the same, but to their surprise I never took any and put in a kick that left the pack. Most of the runners dropped their water to chase after me. I met my coach shortly after the break and said to him, ‘Next stop, Edinburgh!’”

“As I was out on my own I started to run my own race and pull further and further away. At 23 miles I took a stitch after stepping off a high pavement and had to ease down for a bit. It wasn’t until I entered the track that someone told me I had a chance of beating the record. I gave one final spurt and managed just to beat it. If I had known earlier I would have taken more off the time.”

Harry’s 2.25.44 broke Joe McGhee’s championship record by six seconds. Hugo Fox (Shettleston H.) was second in 2.28.57 and George King (Greenock Wellpark) third in 2.37.20. Jimmy Garvie (Vale of Leven AC) was fourth in 2.40.21 and Andrew Hume (Lochaber AC) fifth in 2.44.36 – maybe they were in the (book front cover) race photograph too. Hamish Robertson (ESH) was sixth in 2.46.07.

“After the race I ate a couple of oranges, had a shower and then went for a three course meal. My time was the fastest in Britain and the second fastest in the world that year.” Harry Fenion included with his letter an excellent photograph of the leading pack at the five mile point in the 1957 race, with nine athletes still in contention. Not everyone enjoyed the race like Harry – Gordon Porteous remembered having the fight knocked out of him by a fierce hailstorm at Bathgate around the twenty mile mark. He ended up taking the bus to Meadowbank!

Jackie Foster remembered Harry as being under four foot ten in height, but making up for this in speed. “His wee legs seemed like Mickey Mouse toys, where the feet are fixed to a fairly big wheel which spins as the child pushes it away. In one race, I was in fourth position about a hundred yards down on Harry and two others (Fox and Kerr) as they approached the large floral roundabout at Maybury. Harry made the break and ran straight across, through rose bushes, flowers, the lot, and the other pair, anxious to keep up with him, did likewise. The policeman on duty tried to call them back, but they were away! However, he did make me and the others follow the correct route. Later, I asked Harry how it felt to run as fast as he did, in the hope there was some secret he would reveal. He replied that it was ‘sheer hell’.” So that was how he managed to do it – pain tolerance!

Jackie Foster of Edinburgh Southern Harriers, who holds the record for longest letter to the writers of this book, had his best Scottish Marathon in 1959, running 2.32.38 for third place. He ‘retired’ the following year, since he got married and had to work long hours to support his family. He did not compete again until he was forty; and at forty-five was delighted to run only two minutes slower than his P.B.

Jackie’s training was unusual. He started improving once he got rid of Dunlop Green Flash shoes, which ruined his feet, and bought some expensive (£5 a pair) kangaroo-skin shoes made-to-measure by his namesake Foster in Lancashire. These were very comfortable, even if they looked like pit boots! Jackie’s training took the form of long slow runs. When in the RAF he had been advised by Bill McMinnis, the British champion, to learn to stay on his feet for three or four hours.

When in the RAF, it was acceptable to run in vest and shorts; but after Jackie was demobbed, he had problems. He lived in a fairly rough district, and wearing shorts would have labelled him ‘cissy’. His employer considered, like many others at the time, that running was ‘only for them at universities.’ Jackie described his solution. ‘To allow me to train incognito, I always ran in grey flannel trousers which I had ‘customised’ by sewing up the pockets and fly, and having elastic in the seam at the ankles, just like tracksuit bottoms, but not so obvious. I would slip out the tenement where I lived, and a half mile up the road would commence my run. At the weekends this took the form of two hours (never miles) in one direction and two hours back. I had a sixpence sewn into the lining of my trousers, which I kept in case I was suffering from ‘the knock’ (now known as ‘the wall’) when I got back to the outskirts of the town. When this happened I would board a bus at the terminus, and strange were the looks I got from bus conductors as I unpicked my stitched-in sixpence. We had a neighbour, who having watched me returning several times from these long runs, soaking in sweat, and having difficulty in climbing the three flats to my house, said to my mother, ‘There must be something wrong with your Jackie, Mrs Foster, it’s no right for a young man to get in that state just climbing the stair!’ But my secret was safe with my mother – she never let on.’

Since water stations were very few in a marathon race, Jackie experimented by going without drinks. He sucked a large pebble, which seemed to help; and also tried swallowing a heaped soup-spoon of salt to stop cramps. This was hard to do, and as he later learned, dangerous. On the Wednesday before a Saturday marathon, Jackie once attempted to remove the ‘fear of the distance’ by running twenty miles! When running magazines started giving advice, he learned where he had been going wrong!

Tribute is paid to Jimmy Scott – ‘Mr Marathon 1950-60’. Jackie wrote the following. ‘I never learned if Jimmy had ever been a runner or not. We always held him in such respect that any questions would have been rude. A wee bird-like man, dressed in the kilt or Harry Lauder tweeds, he was ‘kenspeckle’ – a true Scot. He never panicked but stood no nonsense and never apologised (had no need to) and had the most amazing ability to organise running events.

The start of the Perth to Dundee in 1951: Jimmy Scott is number 11

A typical example of Jimmy’s contribution to distance running was the ‘Brechin 12 miles’. Jimmy would pick people up in his mini-bus from Glasgow and Edinburgh and anywhere else along the route. He would start, time and marshal the race. He then instructed the Town Clerk who to give the prizes to, before returning us to our homes, usually issuing us with entry forms for the next race. For all this the charge would be about one pound. Hardly enough to cover his petrol, I would imagine. Jimmy suffered at the time by being overshadowed by Dunky Wright, who was a nice man but an extrovert, which Jimmy was not. Jimmy did all the work but Dunky got all the credit.’

Jackie Foster said that he was always intrigued by Hugo Fox’s first name, which seemed exotic for an ordinary fellow. Hugo had been a racing cyclist and then changed to distance running. Once, when he had just moved into a tenement flat with his wife and young family, Hugo set out to explore his new neighbourhood. He was so anxious to discover new running trails that he became badly lost and did not return until hours later. When he checked the map, he found he had run more than thirty-five miles! Hugh Mitchell, Hugo’s Shettleston clubmate and another converted cyclist, remembered that Hugo worked as a metal moulder and never wore socks for running. Hugo had shown his strength as a cyclist by winning specialist events involving sprinting up a steep one mile hill. Another memory from Hugh Mitchell is about his first trip to the Morpeth – Newcastle event with the more experienced Hugo. Mitchell ate steak before the race; Fox preferred bread and jam. When Hugo ran much better than Hugh, the latter learned a lesson! Jimmy Irvine of Bellahouston remembered Hugo Fox as being a specialist marathon runner unlike Harry Fenion, who Jimmy considered classier but inconsistent.

Hugo Fox (Shettleston Harriers) had the experience in 1958, when he was 38 years old, of arriving in the lead during the marathon championship at the six-foot spiked gate at the north end of the old Meadowbank track, to find the park-keeper had not opened it. Undeterred, Hugo climbed over without impaling himself and trotted onto the track to claim his title in a finishing time of 2.31.22. The gate was unlocked in time for the second-placed runner (Alex McDougall, Vale of Leven) to enter with less difficulty and complete the course in 2.32.35. Harry Fenion was third in 2.36.05. Harry complained that Hugo had been on the dole for nine months, with plenty of time to train. This was completely untrue, since Hugo had been working a five-day week in the heat and dust of a foundry, plus two nights a week overtime; as well as training up to 130 miles per week, including the occasional 30 mile session! Unfortunately, John Duffy of Hadleigh Olympiads, the 1953 champion, who was fit once more, had travelled up but did not compete, because his name was not in the programme. After the race, to his chagrin, he learned that his entry had in fact been received. So he retired from running once more. Much later, in 1984, he moved back to Broxburn, where he became once more two stone overweight, but was still in good health at almost eighty years old.

The three 1958 medallists – Hugo Fox, Alex McDougall and Harry Fenion – went on to compete for Scotland, in unbearably hot conditions, in the Cardiff Commonwealth Games Marathon. Only Alex McDougall reached the finish in a fine seventh place (2.29.58)

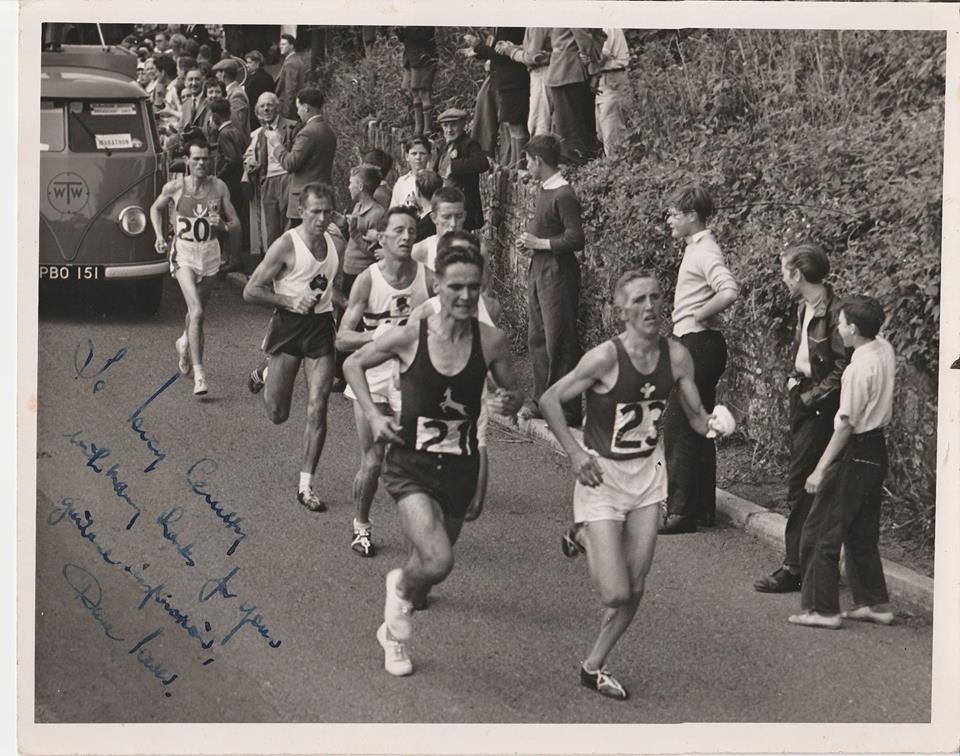

Alex McDougall (20) chasing the pack during the Cardiff Commonwealth Games Marathon. Dave Power (21) was the eventual winner. Note that Dave dedicated this photograph to the famous Percy Cerutty, his coach.

Jackie Foster considered Gordon Eadie (Cambuslang Harriers) as ‘one of nature’s true gentlemen, very modest and unassuming’. Gordon had a powerful build which made him look more like a boxer than a runner. This may have been caused by his having worked as a coalman, perhaps having to carry a hundredweight sack of coal up many four-storey Cambuslang tenements. Rumour had it that Gordon worked one morning before a marathon! Hugh Mitchell remembered that, if Gordon had been delivering coal on Saturday morning, his racing form certainly suffered.

Gordon himself made no mention of such weight-training, but admitted to having run 80 to 100 miles per week. His longer runs were on road (some including fartlek); and his easier efforts were over the country. He wore a vest (with a jersey on top) and shorts. Footwear was Adidas road shoes – or a lighter pair of Fosters for racing.

In the 1959 Scottish Marathon Championship, he remembered that the route was Falkirk to Meadowbank. Hugo Fox, the holder and a good judge of pace, raced into an early lead from the start. By half-distance, Hugo was several minutes in front; but by twenty miles, runners dropped away from the chasing pack and Gordon Eadie found himself alone in second and closing on the leader. However Gordon wrote ‘Hugo was one fox who wouldn’t be caught and finished on the track to win by about a minute.’ Hugo’s time was 2.28.27; Gordon was second in 2.29.22; and Jackie Foster third in 2.32.38.

Eventually, Hugo Fox and his family emigrated to Australia and he took up his old sport of cycling once again. Unfortunately he died of cancer in his mid-fifties. He was a tough, brave, dedicated, determined man.

[ Introduction ] [ The First Four Races ] [ The Sixties ]