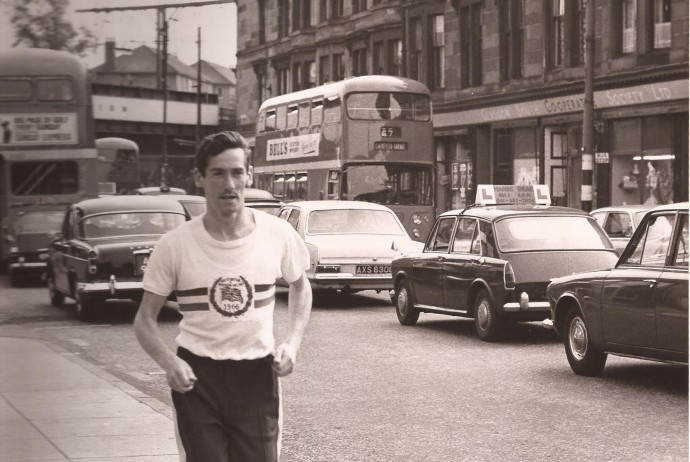

The start of the first ever Tom Scott 10 Miles Road Race

The start of the first ever Tom Scott 10 Miles Road Race

Runners from the recent past, and those who have read and thought about Scottish endurance running, are mildly critical of the current programme of races offered to athletes by governing bodies and race/championship organisers. It takes only a cursory look at the winter programme for any year in the 1960’s (or the 1970’s or the 1980’s) to see that there were cycles of competition where the importance of the events gradually increased, leading the athletes to more and more intense effort and gradually rising standards of performance. Indeed there were cycles inside cycles.

For instance, September was pretty well a fallow month as far as competition was concerned and was followed by the short relays (each runner in a four-man team raced two and a half miles). Road runners spent September (and October) developing a bit more pace, while the half milers and milers were gradually building in a bit of strength. There were four relays in the sequence – McAndrew (road), and three cross-country ones – County, District and (from 1974) National, with a couple of weeks (perhaps including five mile road races like the Allan Scally Relay or the Glasgow University 5) to prepare for the prestigious 8-Man Edinburgh to Glasgow Road Relay (with stages ranging from 4 miles to 7 miles). That was one cycle. Then the runners went in to the cross-country championships proper – County then District then National, then, if you were ambitious and talented, the English National, then the International. Another cycle. Put the relay cycle and the championships cycle together and that was the winter cycle It all made sense.

The same was true of the summer season where there was gradually increasing distance and severity in the races leading up via 10, 12, 14, 15, 18, and 20 miles to the marathon itself. That was the one cycle. Then there were the highland games and sports meetings where the races were all different and it was almost refreshing to run the 20 miles at Strathallan or the 14 at Shotts with the fearful climb up past Kirk o’Shotts.

There was a definite pattern, where the aim was clearly to assist athletes to reach a peak when it mattered; and to raise the standard of Scottish road and endurance running (which could be track 5000m or 10,000m too) across the board. For example, if there were no 20 mile races, then a member of the Scottish Marathon Club would approach the promoter of a meeting which had a road race and offer to help organise a race at that distance. I say ‘a member of the SMC’ but many of the committee were also members of the SAAA with Dunky Wright being the prime example.

In addition a platform was given to these events where the public could see the road runners in action. The SAAA Marathon was held from the actual track and field event championships – after all they were bona fide athletes just like the hurdlers and hammer throwers. The event has now been relegated to a bit part in a massive road race organised more often than not with the prime object of maximising the number of participants. There was the ludicrous instance for some years of the Scottish national championship being held in England.

However, the pattern was set for the runners who could use it and there were also many other distances, mainly on the road, that could be fitted in to a runner’s schedule to help him tweak whatever aspect of his fitness needed a bit more attention at a particular time. For instance Allister Hutton used to run in the Dunky Wright 5 miles+ in April as part of his programme leading to the London Marathon. Enough discussion – it helps to see how a good Scottish runner, who usually managed to peak when it counted, shaped his year.

Lachie Stewart running to work in 1970. Many, possibly most, road runners ran to work and back again

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Back in the 1970s, nearly every road-running Scot was male. [SAAA, SCCU and SWCCU rules did not allow men and women to race together. The only time they might see each other racing was during the SAAA/SWAAA Track and Field Championships – and then only in separate events.] After the advent of City Marathons (starting with Aberdeen in September 1979) could take part in the same races. (The developing Veteran scene was also important in allowing men and women to compete together on the roads.)

Any road-racing specialist would train on a variety of surfaces – track, grass, trails and hills as well as tarmac. In addition, he would almost certainly race on track and cross-country as well as road. Nevertheless, the Road Running Year provided a calendar of events, which allowed the athlete to increase fitness gradually, before peaking for major races like the Tom Scott 10, Scottish Marathon Championship, the Two Bridges 36 and the Edinburgh to Glasgow Road Relay.

The very top road runners had the organisation of their year down to T. It might be of course that that was the difference between the real top men and the ‘nearly top men’. I remember, after the Shotts 14 mile road race race was won by one of the latter, asking one of the former how he felt about defeat and he replied that the winner ‘never won when it mattered.’ In other words he couldn’t peak for the year’s important competitions. Another very good non-championship medal winning athlete was racing quite a lot at one point and when I asked him why his reply was something like, “Well, when you’re running fast and you don’t know why, you have to make the most of it.”

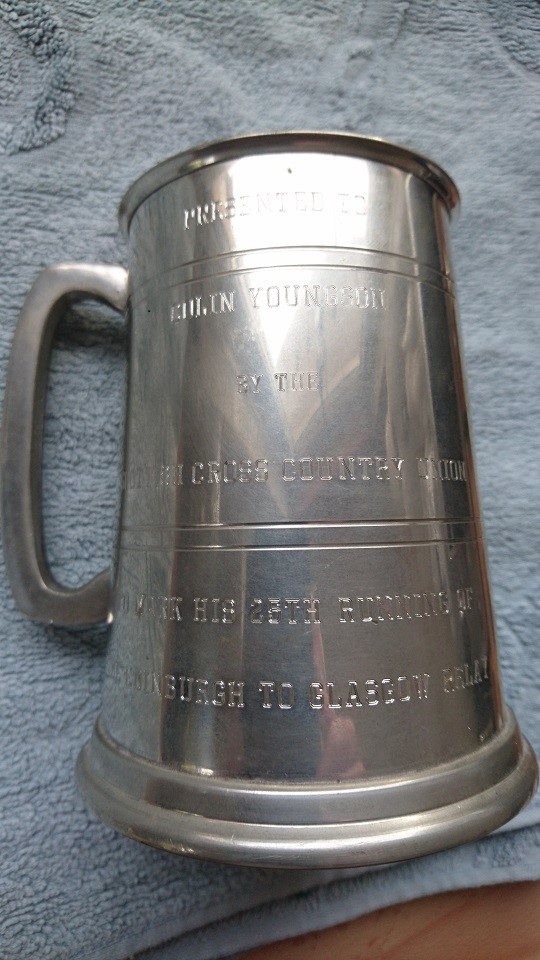

One of our best endurance runners who had success on all surfaces – track and country but especially road – at all age levels is Colin Youngson and we asked him to discuss and explain his racing year and how it was planned.

For example, his best year was 1975 when, representing Edinburgh Southern Harriers, he was training 70 or 80 miles per week and did not suffer injury. No fewer than 24 races were completed that year, and he did peak successfully for the Scottish Marathon and E to G, as well as producing decent performances on cross-country, middle-distance track and (without extra training) the Two Bridges. At the end of such a busy season, he was delighted to be presented with the SAAA Donald McNab Robertson Trophy (for Best Scottish Road Runner of the Year).