We have on the websites some works which are now out of print and difficult to access such as Emmet Farrell’s autobiography, the history of Powderhall and professionalism, the history of the Scottish Marathon Championship by Colin Youngson and Fraser Clyne and several more. This one is exceptional and a bit different in that it is from a current work. It is well worth a read and deals with the elite, classic and unfortunately now defunct Edinburgh to Glasgow Road Relay. The introduction below is by Colin Youngson.

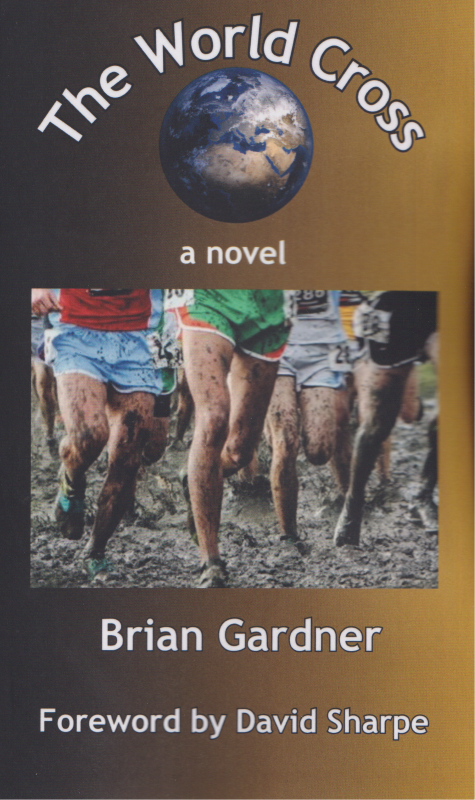

Below is a key chapter from Brian Gardner’s excellent 2025 novel ‘Return to the World Cross’ (which is a sequel to his previous work ‘The World Cross’), both of which are available from amazon.co.uk. These books include a great deal of authentic detail about cross-country running in particular. (Brian himself raced well in the Scottish Senior National and went on to win the M45 division of the annual British Veteran Five Nations Cross-Country Championship.) His main characters are three young runners who look strangely similar, despite coming from different places (Australia, England, Scotland). In this sequel, they are training together and preparing to race for Scotland in the 1979 World Cross-Country Championship in Limerick, Ireland. The E to G is a vital part of their preparation. Although the chapter is fiction, it is firmly based on the real 1978 Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay.

Edinburgh to Glasgow

Extracts from Running Shorts by kind permission of Colin Youngson

The Gathering

‘Now remember, young Danny. This is a team race, the most important one in Scotland. You’ve seven runners relying on you. So hang on to the group until the hill after the Barnton roundabout. Then give it everything you’ve got left. One hundred per cent, all the way to the line, eyeballs out!’

‘Okay, Jock. I promise I’ll do my best.’

‘I’m sure you will. You’ve got the talent and the guts. Right, two minutes to go. I’ll take your tracksuit and pick you up at the other end. Best of luck! I’ll be watching!’

No pressure then, thought Danny nervously as he stripped down to his red vest and shorts, a cold blast of air whipping his bare skin. He edged into the gathering crowd of equally nervous runners, their collective anxiety so acute that he could almost taste it. The freezing wind blew into their faces while they shivered outside the ornate gates of Fettes College, Edinburgh at 10.30am on Sunday 19 November 1978 for the start of the annual Edinburgh to Glasgow road relay. It was going to be a long day.

A whistle blew and a serious-faced official called each runner, in alphabetical order of club, to the white line chalked across the road. Each man was handed a light, metal baton. One, decorated with dark blue ribbon, was presented ceremoniously to the athlete wearing a white vest with two dark horizontal bands hugging his chest as if to keep him slightly warmer. Tradition had it that last year’s winning team carried a baton with a message from the Lord Provost of Edinburgh to his counterpart in Glasgow. This year the honour fell to Edinburgh Western Harriers, whose first stage runner, Menzies Haven, accepted the challenge with suitable grace, and then returned to his shivering.

Our main rivals, so Jock keeps telling us, thought Danny. He looks more confident than I feel. Standing behind the line, he nodded to Haven and waited for the signal to begin the be-all-and-end-all of road races. Jaysus, I wish this bloke would hurry up and get on with it, we’re all freezing our bollox off here.

‘All the best!’ shouted Archie and Eddie from the pavement.

‘Take it steady,’ called Sandy.

Less stressy than Jock, Danny thought appreciatively.

‘Good luck, Danny!’ called his mum tentatively.

Mum’s come all this way on the bus just to see me off, she’s trying really hard, all those years ago we travelled here together to escape Glasgow, now I’m about to run in the opposite direction, Mum never said how she’s getting back though. Then there was no time left to think, because the starter finally called the runners to their marks and raised his arm.

Stage One (five and a half miles) Fettes College to Maybury Roundabout

Crack! went the starting pistol, and the first of eight stages on the far-reaching road to Glasgow began. Long before the athletes disappeared around the first bend, officials and supporters dived into their cars to motor five and a half miles west to the first changeover at the Maybury roundabout. Sandy’s car would continue further to the start of stage three, where Eddie would complete his warm up and wait for Clyde Glen’s second-stage runner to pass him the baton. Archie was due to start the sixth stage and run into Airdrie, home territory.

Meanwhile, Danny was not happy. Something’s not right, he worried, no way should I be this tired and sore already, we haven’t run a mile yet.

‘Come on, Danny! Stay in touch!’ called Jock near the junction of the Craigleith and Queensferry roads.

How did he get here so quick? As promised, Danny was trying his best to do what Jock had asked of him, but he was going backwards. His body wasn’t responding to the pressure of the race. It was one thing to push yourself in training but the stress of competition was something else entirely. It must be the glandular fever, worried Danny. What else could make me feel so shit? There was no escaping that negative conclusion. Nor was there any escape from the race because, unlike another on the roads years ago when Danny gave up and dropped out, this was a relay. Jock’s words rang ominously in his ears: ‘This is a team race. You’ve seven runners relying on you.’

Danny plodded on as another two athletes easily overtook him and sauntered ahead as though they hadn’t a care in the world. And there was nothing that Danny could do about it. ‘You’ve got the talent and the guts,’ Jock had said. What talent, what guts? Danny asked the icy downpour as, clutching his half-frozen gut, he staggered into the gale. Barton roundabout, must get to the Barton roundabout, then eyeballs out and it’s all over, Barton roundabout.

Miles of pain later Danny heard Jock from the roadside again: ‘Last mile, Danny! Stick in there, you’re not that far behind!’ Where the feck is that bloody Barnton roundabout? Following instructions, Danny tried to push hard up a steep hill, and there at last was the elusive way marker, overgrown as though it had been waiting all year for Danny. It must be downhill to the finish from here, please! Glimpsing the road ahead through the foliage, his spirits sagged, because the hill kept going up. Oh, God, Jock did say to hang on until the hill after the roundabout, I forgot, oh no! A wave of weariness slowed the pitifully increased pace that Danny had fought to muster. Another rival passed him and his stride degenerated into a shambling shuffle.

Half a mile to go, downhill to the main road and the changeover zone at the top of the next hill was within his blurred vision. John Black jumped up and down in his eagerness to collect the baton that Danny couldn’t wait to get rid of. When he was close enough to hear his team-mate’s shouts of encouragement above the howling wind, he remembered the extra rep that Sandy had sprung on them in that hill session a few weeks ago, and he dredged up something resembling a sprint, running the last twenty metres with his baton-clenching hand outstretched, and then the cold metal was no longer his responsibility. Thank feck for that.

‘Not too bad, Danny,’ said Jock, clapping him on the back, nearly sending him sprawling. ‘Twelfth, we can catch up. Now come one, here’s your gear. Do a wee jog and get your breath back, then I’ll drive you on to your dad. Don’t hang about though, we haven’t got all day.’

Danny muttered something unintelligible between heaving gasps, hefted his tracksuit top over his aching shoulders and struggled manfully to pull the trousers over his shoes. One wee jog later he was bundled up in the front seat of Jock’s car and looking forward to a rest, although aware that it was bound to be disturbed by the driver’s nonstop encyclopaedic blethering about the greatest relay in Scottish athletics, even greater than Scotland’s history-making triumph in the Commonwealth Games 4×100 metres, apparently. No sooner had Danny sat down than his head was shunted backwards on to the headrest as Jock rammed his foot on the accelerator and the car screeched into action. The team manager was obviously in more of a hurry than his first stage runner had just been.

‘The leader’s a minute and twenty-eight seconds ahead of us. More to the point, we’re only just over a minute slower than Edinburgh Western. John’ll make most of that up.’

1. Albert Park AC (A. Black) 27:03

2. Glasgow College (F. Fyne) 27:04

3. Forrest Runners (G. Killin) 27:09

4. Cambuswee Harriers (C. Connelly) 27:13

5. Edinburgh Western Harriers (M. Haven) 27:24

6. Edict & District AC (A. Muller) 27:25

. . . 12. Clyde Glen AAC (D. O’Toole) 28:31

Stage Two (six miles) Maybury Roundabout to Broxburn

‘Did you spot that official in the striped blazer nicking the fancy baton from the Edinburgh Western runner?’

‘Yeah,’ grunted Danny, gripping his seat tightly as Jock’s car took a corner Grand Prix style.

‘Oh, aye, they gave him an ordinary one instead. They save the special one for the leader at the start of the final stage. Can’t risk losing it before then, you know. They’ll never forget the year that Western runner stopped dead and chucked the baton into a garden. Had enough, he said, until his manager kicked him up the backside and told him to get on with it, not in so many words, mind, and not before a big row with the guy who lived in the house. He’d just shut his front door on his way to collect his News of the World when this metal tube landed in his pride and joy.’ Jock sighed. ‘Aye, great memories.’

‘Erm, do you think you could slow down a wee bit, please?’ asked Danny, feeling sick.

Jock carried on as though his passenger hadn’t spoken. ‘Of course, your stage was like a normal race. The weaker clubs always put their star on the first stage, which is partly why you were back in twelfth, but now it’s every man against the elements. Determination, intelligence, self-motivation—a relay runner needs the lot. Mind you, a good second stage runner can make up a lot of places; most of the guys are still close together.’

‘What’s this stage like?’ asked Danny, feigning interest in the hope that Jock would remember he had a passenger whose life might be in danger.

‘Six miles straight and flat until the last mile uphill. Ideal for track athletes; a lot of fast guys on this one. The best teams put their top men here and stage six. Innes Steward holds the record, and he won the Commonwealth 5000 metres in this city back in 1970. Won the World Cross once as well.’

‘I know,’ gasped Danny as Jock suddenly swerved to avoid a cyclist.

‘Look at that: John’s made up four places already. I told you not to worry.’

I’m worried now, thought Danny, wondering if he dared ask Jock to pull over so that he could throw up. However, Jock was in full stride:

‘Of course, they invite the top twenty clubs in Scotland to this race—there’s even a guest team from Norway this year—but only half a dozen can compete for the medals. That’s how many have the strength in depth for an eight-man relay. Are you feeling better, by the way?’

‘Erm—’

‘Wind your window down, will you?’ interrupted Jock. ‘You’re doing great, John!’ he bellowed, leaning precariously over Danny and breathing stale bacon-and-egg fumes all the way down into his already delicate constitution. ‘They’re all lining up for you! See you at the finish!’ Only just remembering to look at the road ahead, he swung left to avoid an oncoming car, horn blasting. ‘What a man, that John Black, eh? He’s bringing us right back in contention. I told you twelfth wasn’t too bad.’

Please stop, thought Danny. This is worse than the run, even the glandular fever was a walk in the park compared with this.

Jock kept up his obsessive patter for another couple of miles until the car, tyres shrieking in protest, shuddered to a halt on a grass verge near the Broxburn town baths changeover. Danny piled out and immediately emptied the contents of his stomach all over the pavement.

‘You runners are all the same,’ tutted a sour-faced woman walking her dog. ‘Walk on, Lachie, never mind that disgusting boy, you’re much more discreet, aren’t you? Good dog.’

Over at the start line, Eddie glanced across at Danny while he waited for John Black to appear. Poor Danny, he thought, as Sandy and Archie headed over to console their friend. I’ll see you later, I’m a bit busy at the moment, and I’ve got a point to prove.

-

Edinburgh Western Harriers 56:27 (I. Stobs 29:03),

-

Clyde Glen AAC 56:58 (J. Black 28:27—fastest of the stage)

-

Cambuswee Harriers 57:25

-

Albert Park AC 57:39

-

Shingleston Harriers 57:41

-

Edict & District AC 57:43

Stage Three (four and a half miles) Broxburn to Wester Dechmont Farm

The reason that Eddie had a point to prove was that Jock had put him on the shortest stage because he was a poor wee lad who was the first to catch the lurgy. Jock’s skewed logic was that Eddie must be the weakest not only of the three residents of Cairnhill Hospice but also of the whole team. That’s how Eddie had found himself amongst the gnarled legs and bald heads of the older runners clustered around the changeover area. He rubbed his gloved hands up and down his arms and thighs, trying to generate some heat, although thermal long johns would have done a better job. Jogging on the spot, he extended a cold arm, ready to grab the baton from John, who came huffing round the corner in a cloud of steam like he had his own personal generator. So fast was the incoming runner’s approach that he collided with Eddie and shoved him on his way as soon as the precious tube changed hands.

I’ll show Jock, Eddie promised himself as he powered up the first of a series of short hills.

These pathetic humps in the road are easy peasy after training up and down Airdrie’s seven hills, he thought later as he piled up the last of them.

‘You’re doing great!’ shouted Jock from his car, passing perilously close to Eddie’s elbows. ‘You’re catching him!’

It’s hard enough being battered by hailstones without your team manager nearly running you over, Eddie grumbled to himself, then peered ahead at a white vest barely visible through the near-whiteout. Jock was right: he was getting closer.

‘You’re closing in, Eddie!’ called Archie from the front passenger window of his dad’s car.

‘Brilliant running,’ added a pale faced Danny from the back seat.

The course flattened out, the hail mercifully eased off and Eddie had a clear view of Edinburgh Western’s Charlie Fume not far ahead. They were in the last half-mile; was that long enough for Eddie to catch him? Inexorably, stride by stride, the gap closed. Glimpsing a nervous expression on the face of Fume as the leader glanced back, Eddie found another gear but Fume responded, and the space between them stubbornly remained at the next exchange outside a gloomy Wester Dechmont Farm.

‘Well done, man!’ Jock-on-the-spot shouted in his ear, only moments after Eddie had safely transferred the baton into the waiting hand of Jim Montrose. ‘You’ve made up twenty-four seconds on Western. We’re only seven seconds behind now. We’ve got this.’

But there’s another five stages, reasoned Eddie, although he didn’t say it out loud. There was obviously no point in arguing with Jock when he was excited; he never listened. Besides, Eddie didn’t have enough breath to contradict anyone. However, he was feeling good; tired but satisfied. This was a successful comeback on the road to Dublin and the World Cross—or at least to Glasgow, for now.

-

Edinburgh Western Harriers 1:18:51 (C. Fume 22:24)

-

Clyde Glen AAC 1:18:58 (E. Hollingsworth 22:00—fastest)

-

Albert Park AAC 1:19:44

-

Fife Kingdom Runners 1:19:57

-

Cambuswee Harriers 1:19:57

-

Shingleston Harriers 1:20:10

Stage Four (five and a half miles) Wester Dechmont Farm to Armadale

‘Great running, Eddie,’ said Sandy. ‘That must be the fastest of the stage. How are you feeling?’

‘Surprisingly okay, thanks.’

‘Well, you’ve put the team in strong contention now, and Jock’s a happy man.’

‘So I gather.’

‘Anyway, the main thing is that you’ve had a good run and you’re okay, unlike Danny unfortunately.’

‘How is he?’

‘Groggy. He assumed he was still getting over the fever but now he thinks it’s a bug or something. I’m going to drive him and Archie on to stage six. Look, there’s your dad. See you along the road, right? And again, well done.’

‘Brilliant run, Son,’ said Edward, grinning. ‘Proud of you.’

‘Thanks, Dad, thanks for coming.’

‘Wouldn’t have missed it for the world.’

The sound of squealing tyres and roaring engine signalled Jock’s pursuit of his fourth-stage runner. Sandy’s car followed more sedately, a groaning Danny in the back, his pale complexion replaced by a sickly green. Archie fidgeted in the passenger seat. He was wearing his club vest underneath his top to save time, and the over-large race number was irritating him. The stiff paper was inflexible and its sharp corners dug into his armpits. I know, he thought. Mum always keeps a pair of scissors in the glove compartment.

‘Can you see if Jim’s any closer to Rabson?’ asked Sandy, interrupting Archie’s thoughts. ‘I’m having enough trouble seeing the road.’

It had taken longer than expected to locate the leading pair, such was the speed of the chase on the opening, downhill section of the stage. The windscreen wipers were working overtime because the hailstorm had returned with a vengeance. Sandy and Archie peered at the familiar, forward-leaning, long-striding, wide-armed running style of the tall Jim Montrose.

‘Looks to me about the same gap,’ answered Archie. ‘That’s a Commonwealth medallist he’s chasing. It’s a big ask.’

‘What do you reckon then, our steeplechase star or their 1500-metre maestro?’

‘What do you think, Danny?’ Archie said over his shoulder, ‘Can our man do it? He’s a Scottish Native record holder, like you.’

Danny whimpered in response. He knew that Archie meant well, but the distant memory of a record breaking summer only emphasised how crap he felt now. Running to the toilet would be about all he could manage now. Come to think of it . . .

-

Edinburgh Western Harriers 1:48:14 (J. Rabson 29:23—fastest)

-

Clyde Glen AAC 1:48:22 (J. Montrose 29:24)

-

Albert Park AAC 1:50:25

-

Shingleston Harriers 1:50:32

-

Cambuswee Harriers 1:50:55

-

Fife Kingdom Runners 1:51:00

Stage Five (five and a half miles) Armadale to Forrestfield

‘That’s Sandy’s car,’ said Eddie as he and his dad drove past later. ‘And there’s Danny bent over again. He must have been there a while. Dad, turn back! Archie should be at his start! He must be panicking. We need to help.’

Archie was jogging back and forth in the layby while Sandy tried to reassure patient and son at the same time but for different reasons.

‘Sandy, we’ll take Danny home!’ Eddie shouted through the downpour as his dad’s car skidded to a halt.

Moments later, Sandy and an anxious Archie sped away in a race to beat the leaders to the stage six start. A miserable Danny wobbled on weakening legs to unleash another vile torrent from his insides, Eddie and Edward holding him up, preventing him from collapsing into his own gloopy mess.

Sandy’s car slowed down slightly to negotiate the interim changeover zone, too late to find out who had won the battle of the fourth stage, and in too much of a hurry to ask. Jock would surely tell them later. Jock! He must be having a fit at the start of stage six! Quick!

Crossing the ‘border’ from the East to the West of Scotland the hail turned to snow, making visibility even worse. Fortunately, the snow had yet to lie on the road surface, which was Sandy’s excuse for giving the accelerator some welly. They whizzed past tailenders and followers, and then the two leaders suddenly appeared, Edinburgh Western’s ever-reliable Craig Rawson ahead of Clyde Vale’s Rab McRonald, and it looked as though the lead had increased, but not by much.

Archie was too worried about his own impending race to shout encouragement. ‘Drive faster, Dad!’

‘Archie, try not to waste valuable energy panicking about something you can’t control. We did the right thing stopping with Danny. In years to come you’ll look back on this as a good memory because you put your friend’s health first. Anyway, we’ll be there in a few minutes, well before the runners. You’ve got your number on and your racing shoes, you’ve warmed up a wee bit, you did your business in the hedge back there. All you have to do is strip off, jog and stride a bit more, and enjoy a good run. Everything’s going to be fine’

‘You make it sound so simple, Dad,’ said Archie, wriggling out of his tracksuit in the tight space.

‘It is simple. Look, there’s the Forrestfield Inn. Get ready to hop out.’

No sooner had Archie fallen out of the car and rushed to the start than Jock was on him like a ton of bricks. ‘Where have you been? Are you trying to give me a heart attack?’

‘Sorry,’ mumbled Archie, jogging in a circle around the zone.

‘First I thought you were in the pub like that bloke the other year who missed his start. I’ve spent the last, long half-hour of my life staring into the blizzard, like Scott of the Antarctic hoping to be rescued.’ He paused to stare at Archie’s chest. ‘Oh-oh, your number.’

Right on cue, red-striped-blazer man appeared: ‘Whit’ve ye done to yer number?’ he demanded. ‘Tamperin wi race numbers is contrary tae rule fifteen! Clyde Vale could be disqualified for this!’

‘Erm . . .’

‘Hold on, sir, please,’ pleaded Jock, bending at the waist at clasping his hands together submissively. ‘The lad’s come all the way from Australia to run the E to G, so famous is this brilliantly organised race of yours. He doesn’t know the rule about numbers. Where he comes from they use jackets for football goalposts, so what chance has he got of understanding intricate regulations? Have a heart, would you?’

‘All the way across the world tae run in oor relay, ai?’ replied red-stripe, flattered, stroking his chin pensively and staring at Archie’s hopeful expression. ‘Haud oan a wee minute, did Ah no see you oan stage wan?’

‘I thought I saw him on the third stage,’ added another official, helpfully.

‘Come on, Jock,’ said red-stripe. ‘You’ve been in this game lang enough tae ken that ye cannae run the same man on mair than wan stage.’

‘Leaders approaching!’ warned the other official.

‘We’ll huvtae take this matter up again in Glasgow,’ said red-stripe, blowing his whistle.

Splashing through the puddles on the exposed lochside road came Craig Rawson, head down into the gale, hurtling towards the inn without a backward glance. His experience would tell him that although Rab McRonald had not closed the gap, every second could be the difference between his team winning or losing. He sprinted towards his waiting team-mate, who stepped calmly in front of Archie to receive the baton. It was Albert Moor, reigning Scottish Cross-Country Champion and road runner extraordinaire. Waiting in the wings was a rival familiar to Archie: Shingleston’s Nicol Morland.

The big guns were gathering outside this lonely inn near Airdrie for the longest stage of them all. Archie tried manfully to shrug off the effects of his chaotic build up—the glandular fever, the months of isolation, the panic en route to the changeover and now a threat of disqualification—and remind himself that he was the champion of the world, not only of Scotland, not only this windswept corner of Lanarkshire. It’s them that should be worried about me, he mumbled as he stood behind Albert Moor and waited for Rab McRonald and his precious metal cylinder.

-

Edinburgh Western Harriers 2:17:13 (C. Rawson 28:59)

-

Clyde Glen AAC 2:17:23 (R. McRonald 29:01)

-

Albert Park AAC 2:19:31

-

Falkirk Flyers 2:20:50

-

Cambuswee Harriers 2:21:11

-

Fife Kingdom Runners 2:21:24

Stage Six (seven miles) Forrestfield to Airdrie

Archie shuffled into the space vacated by the outgoing Moor and gave a final shout of encouragement to the incoming McRonald. There’s no one else in sight, was Archie’s last, fleeting thought of the nineteen teams that were now out of the equation; his last glance behind when he grabbed the baton from his team-mate. He turned to face front and set off in determined pursuit of the galloping leader of this two-horse race in the grand stakes of the E to G.

Snow gave way to sleet and then rain, all in the opening miles of undulation. Edinburgh Western had started the stage ten seconds in front of Clyde Glen but it might as well have been ten minutes for all that Archie could see of his white-vested target in the enveloping murk. With each bend and rise in the road, Moor flitted in and out of his pursuer’s vision. One minute he seemed to be closer, the next further away. Relentlessly, Archie kept up the chase, racing against the elements and his elusive prey, the Arctic wind a bitter enemy. A road that was also taking Archie into familiar training haunts. He rounded another bend and sloshed through a flood underneath a bridge, which he knew was three miles away from Airdrie Cenotaph and the end of this stage. Only three miles, nearly all downhill, on a surface that remained solid despite the constant battering from the skies. Surely an insignificant distance for a well-trained runner who had conquered the world on the stormiest of days in the muddiest fields imaginable.

The road straightened out on the relentlessly long main street of Plains, and still Archie maintained his dogged pursuit, and still his rival remained just out of reach. Down a leafy glen, up the other side and into Clarkston, through traffic lights—red, but controlled by a police officer signalling all vehicles to stop. Just as well, because there was no chance of Archie stopping; he sprinted straight across, utterly single-minded in his effort to reduce the rift.

Downhill again, zipping over the black and white chequered roundabout known as the terminus, although trams had long since ceased to roll through the town. Careering down Forrest Street, past the big posh houses and into Airdrie’s thoroughfare. Calm the breathing, check knee-lift, grip the baton safely and concentrate, work hard but don’t overdo it, keep a bit in hand for the final flourish. Crashing through another set of red lights at Airdrie Cross, scudding alongside the town hall and public baths, leaving the shops behind, flashing past the big Tudor Hotel. What’s that sound, not a bugle? And there was Westend Park on the left, and just beyond, the cenotaph and its attendant crowd of matchstick figures, Lowry style, and still Archie was still the same distance in arrears! Sprint!

‘Sprint!’ echoed Jock. ‘Eyeballs out!’

‘Last effort, Archie!’ cried his dad. ‘Big finish!’

Archie sprinted, eyes popping out of their sockets, staring straight ahead at the eager face of the waiting Innes Gillanders. Tired legs carried a wheezing Archie and steered his priceless cargo into the dock-like, grasping fingers of his team-mate. ‘Go, go!’ he gasped, and Clyde Glen AAC entered the penultimate stage in their now accustomed role of pursuing Edinburgh Western Harriers.

-

Edinburgh Western Harriers 2:50:59 (A. Moor 33:46)

-

Clyde Glen AAC 2:51:11 (A. MacTavish 33:48)

-

Albert Park 2:54:40

-

Falkirk Flyers 2:55:23

-

Cambuswee Harriers 2:55:47

-

Shingleston Harriers 2:56:00 (N. Morland 33:17—fastest)

Stage Seven (five and a half miles) Airdrie to Barrachnie

‘Great run, lad!’ shouted the ever-present Jock. ‘You’ve set Innes up nicely. Twelve seconds is nothing to him. Brilliant run by Nicol Morland, though—33:17 is some going, but his team’s no threat, they’re miles behind. No, it’s us against those Prima donnas from Edinburgh who think they own the place because they’ve won everything else this year. Well, they’re not going to win the main event. We’ve got them now, you wait and see. Right, I’m away to the next changeover. See you at the finish, and don’t worry: I’ll smooth over that number problem. Nothing’s going to get in our way today!’

Archie slumped over the bonnet of a parked car and waited for Sandy.

‘Dad?’ he asked, after absorbing his less obsessive praise. ‘Was that really a bugle or was I hearing things?’

Half an hour later they drove through the final changeover zone, having just missed the exchange between Gillanders and Clyde Glen’s anchor leg runner. Sandy spotted his friend and Scotland team manager, Neil, heading for his car.

‘Hey, Neil,’ he called out of the window, slowing the car to a crawl. ‘What’s happening?’

‘Big rumpus. The official got himself into a right fankle, wondering who to give the fancy baton to. Gillanders was closing up on Andy Robinson so fast that the poor bloke was hovering between the two eighth-stage runners. First of all he pointed it to your man, then to the Edinburgh guy. It was comical. Anyway, Robinson just held off your man, and his mate grabbed the fancy baton off the official to make up his mind for him. Then, what do you know, Gillanders clattered into his mate and their ordinary baton flew up in the air. Both of your blokes caught it between them and then away went your glory-leg man. You couldn’t make it up.’

‘That’s hilarious, Neil.’

‘There’s more, wait til you hear this. That tuneless trumpeter from Edinburgh Western played The Last Post when your man ran past him, still some way behind Robinson at that point. You know what your Jock told him when he caught up with him here? He said he was premature in his ejaculation, which I thought was quite witty for Jock in all this excitement. And you know what he said after that? He told him to stick his bloody bugle up his—’

A blast of a horn warned Sandy that his car was blocking the road. He jolted into action and joined the line of cars leaving the housing schemes of Baillieston behind and following the leading duo on the final stage towards Glasgow’s George Square—a place steeped in Scottish history, where pens were poised to write a new page in the history of Scottish road relay running.

-

Edinburgh Western Harriers 3:17:34 (A. Robinson 26:35)

-

Clyde Glen AAC 3:17:35 (I. Gillanders 26:24)

-

Albert Park AAC 3:21:49

-

Shingleston Harriers 3:22:22 (S. Weston 26:22—fastest)

-

Falkirk Flyers 3:22:31

-

Edinburgh Central AC 3:23:07

Stage Eight (five miles) Barrachnie to George Square

Jock had said that he could name any one of half a dozen club-standard runners to fill the final place in the team of the century. In top junior Baird McCloy, he had far more than that minimum requirement. The pesky bugler and the rest of the Edinburgh Western contingent placed their trust in seasoned campaigner Irvine Morton, but it soon became clear that he was struggling in the renewed blizzard. By the time that Sandy edged his car ahead of the front-runner it was the Clyde Glen man who held a commanding lead in the busy streets of Glasgow.

‘He’s going away,’ said Archie. ‘All those miles running west, chasing Western, and now it’s too easy. Jock must be in a lather.’

‘Definitely. It’s a proud day for the team manager.’

Jock was jumping up and down in childlike delight at the finish line in the shadows of the dignified monuments in George Square when Sandy and Archie arrived.

‘Team of the century! I told you it was our turn to win this year!’ he spluttered to anyone who might be listening.

‘Congratulations, Jock,’ said the Edinburgh Western team manager, patting his counterpart on the back. ‘The best team won.’

Jock calmed down momentarily to acknowledge his rival’s sporting gesture, and then resumed his bouncing on the spot when the rapidly striding figure of Baird McCloy entered the Square. This was Jock’s crowning achievement. Years of domination by the team from the east with the name from the west, and now with only seconds of almost four hours of road racing remaining, the usurpers named after the west’s famous river were flowing unimpeded towards a glorious victory. Baton raised high above his head, Lanarkshire lad McCloy breasted the tape and broke the hearts of Midlothian.

For the first time in his life Jock was lost for words. He bent over and coughed into a slushy puddle. The stress of months of preparation, miles of tension and anticipation on the road and the exertions of his demented leaping up and down had finally caught up with him, here at the climax of it all in Scotland’s so-called second city. There was nothing second best about Jock’s team of the century though.

‘Superb management,’ said Neil as he, Sandy and Archie joined the crowd gathering in concern around the victor apparently choking.

‘Ma-cough-marvellous! I-cough-told you we’d do it!’

‘You did at that, Jock.’

‘And do you know what? Cough. The team wasn’t even at its best. Cough. Rab’s not fully fit, Innes obviously enjoyed a long holiday after the Commonwealths, there was that mix-up with the baton at the last changeover, and your three lads haven’t properly recovered from the glandular fever, have they?’ Jock asked Sandy. ‘Where’s the other two by the way?’

‘Eddie and his dad are looking after Danny back home in Airdrie. Archie and I are going to head off soon to check on the poor lad . He’s had a rough day of it.’

‘There you go then,’ said Jock. ‘I hope he’s okay. Anyway, just think what we can achieve when everyone’s fit. Roll on, Livingston.’

‘Livingston?’ asked Archie.

‘That’s where the Scottish Cross-Country is this season,’ explained Neil. ‘Jock won’t be the only team manager keeping an eye on you Clyde Glen stars.’

‘Oh, aye,’ added Jock. ‘You’ve got three months to get fully fit, and then we’ll show those Edinburgh guys that their days of domination are over. Look, there’s that red-striped official taking the poncy baton off the Edinburgh guy and passing it to our Baird, and there’s the Glasgow provost waiting for it.’

‘Oh-oh, Jock,’ said Sandy. ‘Red-stripe’s coming this way.’

‘Hmm, cough.’

‘Congratulations, Jock,’ said red-stripe. ‘Noo, aboot yon race number . . .’

-

Clyde Glen AAC 3:46:07 (B. McCloy 28:32—fastest)

-

Edinburgh Western Harriers 3:48:42 (I. Morton 31:08)

-

Albert Park AAC 3:51:35

-

Shingleston Harriers 3:52:29

-

Edinburgh Central AC 3:53:07

-

Falkirk Flyers 3:53:08